Midweek Review

Vignettes of the Open-Air Theatre

by Prof. K. N. O. Dharmadasa

It is indisputably The Open-Air Theatre – the first of its kind in the country and the most well-known. There indeed are some other similar constructions, like the one at Vihara Maha Devi Park, Colombo. But when theatre lovers talk of ‘the Open-Air Theatre’, the reference is unmistakably to the Open-Air Theatre in the ‘University Park’, Peradeniya. Incidentally, the appellation ‘University Park’ was a creation of Sir Ivor Jennings, the Founder Vice Chancellor of the University. The area where the university buildings were located was known by this name. Sir Ivor was so enamoured of the site that he called it ‘one of the most beautiful environments in the world” (his autobiography The Road to Peradeniya,198). His Annual Reports usually had a sub-section titled ‘University Park’; he reported on the building programme and the landscaping, etc. Coming back to the Open-Air Theatre, which was constructed three years after he left in January 1955, undoubtedly adds to the beauty of the whole landscape – a good example of how a tastefully constructed structure which blends with the surroundings can enhance the natural beauty of a place.

The conception

The Open-Air Theatre was ceremonially declared open in early 1958. The first drama staged there was Sarchchandra’s epoch making Maname. As all theatre lovers know, the initial staging of Maname was on Nov. 3, 1956 at the Lionel Wendt Theatre in Colombo and nearly 100 performances would have taken place during the 15 or so months before it was staged at the newly constructed Open-Air Theatre in Peradeniya. Prof. Sarachchandra in his Memoirs, Pin Ethi Sarasavi Waramak Denne, (published in 1985) gives a detailed account of the founding of the Open-Air Theatre, which aptly bears his name today.

Maname had already been staged and the first accolade had come from an unusual quarter. Regi Siriwardene, a highly respected critic and journalist attached to the Lake House Group of Newspapers called it “the finest thing I have seen on the Sinhalese stage” (Ceylon Daily News, Nov. 5) Many shows followed in Colombo, Kandy and other cities and several other writers to the English newspapers showered praise on this remarkable achievement as exemplifying what the national theatrical form could be. But the Sinhalese newspapers remained silent for quite some time and Sarachchandra kept wondering why it was so. “Was it due to the habitual antipathy towards the University by most of the journalists or was it because they failed to understand what Maname signified?” But the breakthrough came eventually. Sri Chandraratne Manavasinghe, the highly respected writer and journalist attached to the editorial staff of the daily Lankadeepa, wrote a highly complimentary review of the play in his daily column Waga –Tuga and called it an Abhiranga (super-drama).

Sarachchandra with his vast experience in Oriental and Occidental theatre traditions, believed that “a super-performance of Maname could be done, not on a proscenium stage which was meant for staging naturalistic plays, but on a circular stage, (ranga madala)”. And he was on the lookout for such a place … amidst the hilly terrain of Peradeniya. He adds:

“Those days I was residing in one of the three bungalows on Sanghamitta Hill. While descending the hill and walking towards the Arts Block, I noticed a piece of land concave in shape, like a part of a broken clay pot. This was a terraced paddy field which had been abandoned and was overgrown with weeds. At the bottom of the land was a flat space. Although I had been passing that place daily it was only after I started thinking of an open-air theatre that it struck me as a suitable location for what is known as an Amphitheatre – an auditorium with a stage. The space at the bottom could be used as a stage and the audience could sit in the terraces” (p. 209)

Acoustics

Sarachchandra was not prepared to rush into conclusions. Although the land appeared suitable in appearance, there was a crucial consideration when it came to an open-air theatre. “It was essential,” he adds. “To find out what the acoustics of this place was like for theatre performance. One evening I went there with a group of students. I think Gunasena Galappaththi was one of them. I placed several of them in various places in the pit and made them talk and sing. Then I realized that it was a place with natural amplification of sound. The Epidorus Amphitheatre in Greece came to my mind. If you stand anywhere and strike a match you will be able to hear it. (p.210).

Sarachchandra was not prepared to rush into conclusions. Although the land appeared suitable in appearance, there was a crucial consideration when it came to an open-air theatre. “It was essential,” he adds. “To find out what the acoustics of this place was like for theatre performance. One evening I went there with a group of students. I think Gunasena Galappaththi was one of them. I placed several of them in various places in the pit and made them talk and sing. Then I realized that it was a place with natural amplification of sound. The Epidorus Amphitheatre in Greece came to my mind. If you stand anywhere and strike a match you will be able to hear it. (p.210).

Now the problem was that of the logistics. At this time (1956-7) Sarachchandra was only a lecturer. He had no ‘clout’ to order officials in the administration. Of course, his fame and prestige were growing rapidly and by 1960 a special Chair of Sinhala was created for him, which was the first such occasion in the history of the University. But that is anticipating events. We resume the story of the construction of the OAT as narrated by Sarachchandra himself. Sarachchandra says:

“I had no power to give orders to the Works Department or to the Administrative Section. That could be done only by the Vice Chancellor or the Registrar. The expenses involved in constructing even an amphitheatre at the site I mentioned would be minimal. What had to be done was cutting and removing the weeds on the terraces, constructing in cement a circular stage at the bottom and putting up a cadjan shed behind it.” (pp. 210-11)

Now, the dilemma Sarachchandra was faced with was whether or not the Vice Chancellor would accept his proposal to construct an open-air theatre. Sarachchandra’s estimation of the Vice Chancellor Sir Nicholas Attygalle was not at all complimentary. “Like most people of the English-speaking upper class,” says Sarachchandra,

“He was completely devoid of any taste for the arts (kalaa vihiina). Although he was a Professor in the Faculty of Medicine before becoming Vice Chancellor, his range of knowledge was small (alpasruta). He did not have even a modicum of interest on theatre, literature, music, etc. I do not know whether he had read any other book outside the field of medicine.” (p.211).

For the present-day reader, I have to give an explanation. Without digressing too far it needs be noted that during the Attygalle phase of the University administration, there was a sharp division in the academic staff as pro-Attydalle and anti-Attygalle, and that was due largely to the dictatorial administrative style of the Vice Chancellor. It is clear where Sarachchandra stood in this division. In any case Prof. Attygalle had not displayed any interest in the arts. And the problem then was how to get the approval of a man like that for the construction of an open-air theatre. Then the miracle happened once again.

The Vice Chancellor came to know about Maname under fortuitous if not trivial circumstances. Continues Sarachchandra, “He came to know for the first time that a play named Maname had been created by a person named Sarachchandra, who was on his staff and that it was winning accolades in the country, from a group of lecturers who used to sit before his table daily, rumour-mongering and engaging in empty prattle. It was difficult for Mr. Attygalle, who had never seen a play, to understand what Maname was. He did not want to understand either. But because of the persuasions, he summoned me and asked me what this wondrous thing I had done was about which he had heard so much.” (p.211)

Sarachchandra now had to be humble. “I told him it was not a big miracle, but the production of a play. ‘Then why are they praising it so much’ he asked ‘and telling me I should see it somehow?” Next came the crucial question “Can it be shown in the University?” This created the opening Sarachchandra was looking for.

“I told him that there is no suitable theatre in the University where it could be shown. ‘But would it be possible,’ Then I asked, ‘whether such and such a place could be prepared for the purpose?’ He summoned the officers immediately and ordered them to construct without delay an open-air theatre on the site I had mentioned.” (p.211)

Sarachchandra then describes in humorous Sinhala how the officials set about their job and finished it in no time:

“The officers bent themselves double and treble, ran there, cut down the bush, pounded the ground, got a pretty circular stage made in cement, got a cadjan shed put up and created an amphitheatre in two or three days.” (p.211)

Sarachchandra’s narration about the opening of the Open-Air Theatre is quite informative, albeit with a touch of humour:

“On that day was presented the first ‘performance on orders’ (agnapita rangaya) of Maname before an audience which consisted of the Vice Chancellor, some members of the staff, Mr. Kilpatrick of the Rockefeller Foundation, the students and village folk coming from the neighbourhood. That was the day the Open-Air Theatre in Peradeniya was born. Maname came into being on 3rd November, 1956. It was performed in an ideal atmosphere, without damaging the traditional Nadagam style, at the Open-Air Theatre on a night of either February or March 1958 ((p. 212).

Mr. Kilpatrick referred to here is the Rockefeller Foundation representative who, after reading Sarachchandra’s well researched The Sinhalese Folk Play (1952) had granted him a travelling scholarship some years ago, to study theatre in any country he wished, which eventually enabled him to see the Japanese Kabuki giving him the clue to bring a traditional folk theatre on modern stage. Let us get back again to our discussion about the Peradeniya Open Air Theatre.

Improvements

During the early days the ‘seating’ terraces were levelled earth with trimmed grass. As the location, an abandoned paddy field with a running stream in the vicinity was damp the whole year round, it was a good breeding ground for leeches. During the days when plays were being performed, the leeches had a gala time. I myself remember my first experience of watching a play there, back in my first year 1959, Dayanada Gunawardena’s Parassa. There was a blood patch on my trousers and it was no easy task stopping the blood flow because it is said leeches inject their saliva, which prevents blood-clotting! Eventually, however, the terraces came to be constructed in granite and the leach population dwindled although one finds a stray leech climbing up one’s legs if one were to stand on the grass. Another casualty of the granite and cement intrusion was the lushly grown Tabubia Rosea tree which used to spread a carpet of light pink flowers on the terraces during the blooming season. Most probably its roots were suffocated by the cement construction.

The original Green Room, which was a cadjan shed as described by Sarachchandra, later came to be a Takaran shed with walls and roof made of galvanized sheets. It was painted in Green! Anyway, in the 1990s when I was the Chairman of the Arts Council, we managed to get a permanent Green Room constructed during the period 1991-92. I gratefully acknowledge the support we got from the Vice Chancellors Prof. Lakshman Jayatilaka and Prof. J. M. Gunadasa for these improvements. It was on March 24, 1993 that we named the theatre as Sarachchandra Elimahan Ranga Pitaya in honour of the man who had done so much for the Sri Lankan drama. I remember him attending the naming ceremony (again with a performance of Maname) and rising from his seat in the front row, facing the audience acknowledging the cheering of the massive crowd with hands clasped in Namaskara. He left us three years later on 16 August 1996.

An event highly significant in the annals of Sinhala theatre is the first staging of Sinhabahu on 31 August, 1961 at the Open-Air Theatre. There was a slight drizzle at the start of the performance which stopped after some time. I remember sitting on the damp grass watching the play on that memorable night. Fifty years later, on 28 November 2011, we were able to commemorate the Golden Jubilee of this play at the same venue, although we badly missed our beloved Guru. Special mention should be made of the patronage we received from the Vice Chancellor, Prof. S.B. Abeykoon, who made arrangements to show the play free of charge. Incidentally, he hails from Uda Peradeniya and has told us how as a child he had watched shows at the OAT seated on his father’s lap!

Drama Festivals

The most important annual event in the Open-Air Theatre was the Annual Drama Festival. In the good old days before the university calendar got disrupted, the Drama Festival was held in mid or the last week of January. This was the beginning of the third Term which consisted of 10 weeks of teaching and the examinations were scheduled for the last two weeks of March. January was selected because it was normally a dry period with no rains to disrupt the shows.

here would be a slight drizzle as the festival begins. Normally, the festival lasts seven or eight days and two invariable items would be Maname and later, Sinhabahu. when that university ‘term system’ got severely disrupted, the drama festivals came to be held in different periods, even during rainy seasons. One of the indelible memories I have of the OAT is of a show in the 1990s, when the packed audience sat there with rapt attention in the pouring rain.

When the festival is on, there is a festive atmosphere in the area. When the evening falls, people start gathering and various itinerant traders come, vendors of gram, peanuts, sara vita and even balloon vendors because sometimes parents come there with their children. I forgot to mention that this is not a mere university drama festival but a drama festival for the whole vicinity. People from Uda Peradeniya, Hidagala as well as other adjoining villages throng to the Open-Air Theatre during the festival.

Acid Test

There is a belief among theatre lovers in Sri Lanka that if a play could be staged at the Open-Air Theatre and come off unscathed that would be the best touchstone for ascertaining its success. It is difficult to explain the origins of this belief. With my experience from 1959 onwards, I can say that in those early days there was no unsuccessful play as such. It could be that all the plays staged there were good plays, carefully selected by the Arts Council, which managed the Annual Drama Festival. But in the 1970s, there were three unfortunate incidents, all of them involving plays by leading dramatists in the country, where the jeering by the crowd became unmanageable and the performances had to be abandoned. The first instance, if my memory is correct, was the play Sarana Siyot Se Putuni Hamba Yana by Henry Jayasena. The second, I think was Bak Maha Akunu by Dayananda Gunawardena. And the third was Cherry Watta by Somalatha Subasinghe. If my memory is correct, the failure of the first and the last mentioned, Sarana Siyot Se…and Cherry Watta were due to their lack of dramatic concentration and long spells of dialogue which tired the audience. In the case of Bak MahaAkunu what provoked the jeering was the over enthusiasm of the actor who played the role of the servant Jason. He got carried away in his diatribe against his master, the Mudalituma, who was making advances to his beloved Pabulina . He came on stage with sarong half tucked up, and uttered something that just fell short of a four-letter word and the audience protested immediately. The furore was uncontrollable and the show had to be abandoned. Possibly, these early experiences led to the belief that a show at the OAT is an acid test for the success for a play. At the same time, it needs be added that the two “failed” plays, Sarana Siyot Se and Cherry Watta were plays not quite suitable for an open-air theatre. But this leads to a theoretical problem which needs be addressed separately. The three incidents mentioned were sad occasions as all three dramatists involved were people dedicated to their vocation. Furthermore, Dayananda and Somalatha were respected alumni of the Peradeniya University.

It needs mention that that not all dramatists were prepared to take these judgments of the OAT audience lying down. I remember two incidents, both in the 1980s when the dramatists came on stage and challenged the jeering audience. One instance was when Namel Weeramuni, who was giving a performance of his Nettukkari, where he himself was playing a leading role. Incidentally, he himself is an alumnus of Peradeniya of the period when the OAT was constructed and he would have been thoroughly annoyed at this behaviour of the campus denizens of a later period. He came on stage in his costume and addressed the audience telling them that it was with great difficulty that anybody produces a drama and it should not be treated with such disrespect. Whoever did not like the play, could leave the audience allowing those who wished to stay back, watch the play. The shouting died down after some time and the play was resumed. The other incident involved Solomon Fonseka, who had won accolades all round for his star performance in Dayananda Gumawardena’s Nari Bena, some years back. Since then he had studied the art of theatre in a European university and obtained a Doctorate. This time he had produced his own play and was staging it in the OAT. For some reason which I forget, the audience became restive and started hooting. Solomon stopped the show, sent the other actors to the Green Room and addressed the audience in a defiant tone: “You fellows (umbala) call yourself educated. But what kind of education do you have if you are not civilized enough to behave yourself in a theatre? If someone does not like a play he can walk out and allow those who want to watch it, do so.” That worked. And the audience became quiet allowing the show to continue.

PS The reader would have noticed that I have refrained from using the trivial term “wala” which has come into much use in referring to this theatre. That is because it demeans the stature of this special theatre in our country.

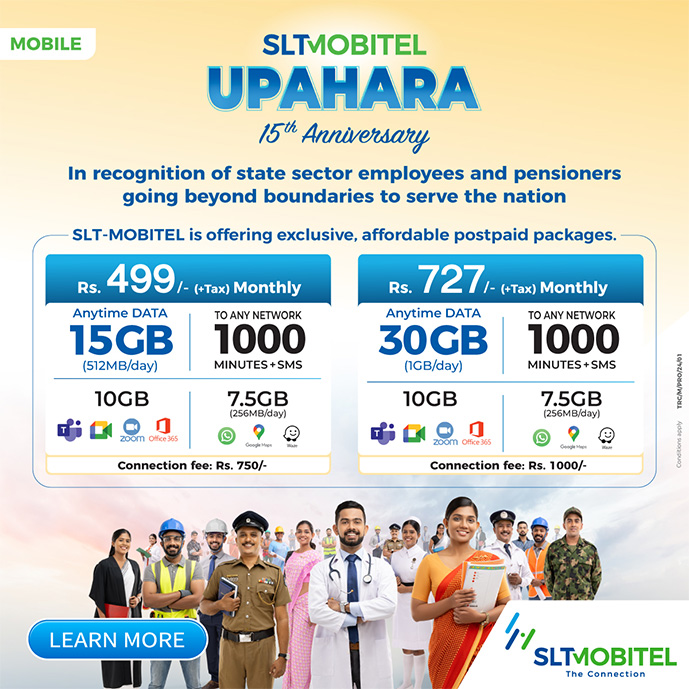

- News Advertiesment

See Kapruka’s top selling online shopping categories such as Toys, Grocery, Flowers, Birthday Cakes, Fruits, Chocolates, Clothing and Electronics. Also see Kapruka’s unique online services such as Money Remittence,News, Courier/Delivery, Food Delivery and over 700 top brands. Also get products from Amazon & Ebay via Kapruka Gloabal Shop into Sri Lanka.

Midweek Review

‘Professor of English Language Teaching’

It is a pleasure to be here today, when the University resumes postgraduate work in English and Education which we first embarked on over 20 years ago. The presence of a Professor on English Language Teaching from Kelaniya makes clear that the concept has now been mainstreamed, which is a cause for great satisfaction.

Twenty years ago, this was not the case. Our initiative was looked at askance, as indeed was the initiative which Prof. Arjuna Aluwihare engaged in as UGC Chairman to make degrees in English more widely available. Those were the days in which the three established Departments of English in the University system, at Peradeniya and Kelaniya and Colombo, were unbelievably conservative. Their contempt for his efforts made him turn to Sri Jayewardenepura, which did not even have a Department of English then and only offered it as one amongst three subjects for a General Degree.

Twenty years ago, this was not the case. Our initiative was looked at askance, as indeed was the initiative which Prof. Arjuna Aluwihare engaged in as UGC Chairman to make degrees in English more widely available. Those were the days in which the three established Departments of English in the University system, at Peradeniya and Kelaniya and Colombo, were unbelievably conservative. Their contempt for his efforts made him turn to Sri Jayewardenepura, which did not even have a Department of English then and only offered it as one amongst three subjects for a General Degree.

Ironically, the most dogmatic defence of this exclusivity came from Colombo, where the pioneer in English teaching had been Prof. Chitra Wickramasuriya, whose expertise was, in fact, in English teaching. But her successor, when I tried to suggest reforms, told me proudly that their graduates could go on to do postgraduate degrees at Cambridge. I suppose that, for generations brought up on idolization of E. F. C. Ludowyke, that was the acme of intellectual achievement.

I should note that the sort of idealization of Ludowyke, the then academic establishment engaged in was unfair to a very broadminded man. It was the Kelaniya establishment that claimed that he ‘maintained high standards, but was rarefied and Eurocentric and had an inhibiting effect on creative writing’. This was quite preposterous coming from someone who removed all Sri Lankan and other post-colonial writing from an Advanced Level English syllabus. That syllabus, I should mention, began with Jacobean poetry about the cherry-cheeked charms of Englishwomen. And such a characterization of Ludowyke totally ignored his roots in Sri Lanka, his work in drama which helped Sarachchandra so much, and his writing including ‘Those Long Afternoons’, which I am delighted that a former Sabaragamuwa student, C K Jayanetti, hopes to resurrect.

I have gone at some length into the situation in the nineties because I notice that your syllabus includes in the very first semester study of ‘Paradigms in Sri Lankan English Education’. This is an excellent idea, something which we did not have in our long-ago syllabus. But that was perhaps understandable since there was little to study then except a history of increasing exclusivity, and a betrayal of the excuse for getting the additional funding those English Departments received. They claimed to be developing teachers of English for the nation; complete nonsense, since those who were knowledgeable about cherries ripening in a face were not likely to move to rural areas in Sri Lanka to teach English. It was left to the products of Aluwihare’s initiative to undertake that task.

Another absurdity of that period, which seems so far away now, was resistance to training for teaching within the university system. When I restarted English medium education in the state system in Sri Lanka, in 2001, and realized what an uphill struggle it was to find competent teachers, I wrote to all the universities asking that they introduce modules in teacher training. I met condign refusal from all except, I should note with continuing gratitude, from the University of Sri Jayewardenepura, where Paru Nagasunderam introduced it for the external degree. When I started that degree, I had taken a leaf out of Kelaniya’s book and, in addition to English Literature and English Language, taught as two separate subjects given the language development needs of students, made the third subject Classics. But in time I realized that was not at all useful. Thankfully, that left a hole which ELT filled admirably at the turn of the century.

The title of your keynote speaker today, Professor of English Language Teaching, is clear evidence of how far we have come from those distant days, and how thankful we should be that a new generation of practical academics such as her and Dinali Fernando at Kelaniya, Chitra Jayatilleke and Madhubhashini Ratnayake at USJP and the lively lot at the Postgraduate Institute of English at the Open University are now making the running. I hope Sabaragamuwa under its current team will once again take its former place at the forefront of innovation.

To get back to your curriculum, I have been asked to teach for the paper on Advanced Reading and Writing in English. I worried about this at first since it is a very long time since I have taught, and I feel the old energy and enthusiasm are rapidly fading. But having seen the care with which the syllabus has been designed, I thought I should try to revive my flagging capabilities.

However, I have suggested that the university prescribe a textbook for this course since I think it is essential, if the rounded reading prescribed is to be done, that students should have ready access to a range of material. One of the reasons I began while at the British Council an intensive programme of publications was that students did not read round their texts. If a novel was prescribed, they read that novel and nothing more. If particular poems were prescribed, they read those poems and nothing more. This was especially damaging in the latter case since the more one read of any poet the more one understood what he was expressing.

Though given the short notice I could not prepare anything, I remembered a series of school textbooks I had been asked to prepare about 15 years ago by International Book House for what were termed international schools offering the local syllabus in the English medium. Obviously, the appalling textbooks produced by the Ministry of Education in those days for the rather primitive English syllabus were unsuitable for students with more advanced English. So, I put together more sophisticated readers which proved popular. I was heartened too by a very positive review of these by Dinali Fernando, now at Kelaniya, whose approach to students has always been both sympathetic and practical.

I hope then that, in addition to the texts from the book that I will discuss, students will read other texts in the book. In addition to poetry and fiction the book has texts on politics and history and law and international relations, about which one would hope postgraduate students would want some basic understanding.

Similarly, I do hope whoever teaches about Paradigms in English Education will prescribe a textbook so that students will understand more about what has been going on. Unfortunately, there has been little published about this but at least some students will I think benefit from my book on English and Education: In Search of Equity and Excellence? which Godage & Bros brought out in 2016. And then there was Lakmahal Justified: Taking English to the People, which came out in 2018, though that covers other topics too and only particular chapters will be relevant.

The former book is bulky but I believe it is entertaining as well. So, to conclude I will quote from it, to show what should not be done in Education and English. For instance, it is heartening that you are concerned with ‘social integration, co-existence and intercultural harmony’ and that you want to encourage ‘sensitivity towards different cultural and linguistic identities’. But for heaven’s sake do not do it as the NIE did several years ago in exaggerating differences. In those dark days, they produced textbooks which declared that ‘Muslims are better known as heavy eaters and have introduced many tasty dishes to the country. Watalappam and Buriani are some of these dishes. A distinguished feature of the Muslims is that they sit on the floor and eat food from a single plate to show their brotherhood. They eat string hoppers and hoppers for breakfast. They have rice and curry for lunch and dinner.’ The Sinhalese have ‘three hearty meals a day’ and ‘The ladies wear the saree with a difference and it is called the Kandyan saree’. Conversely, the Tamils ‘who live mainly in the northern and eastern provinces … speak the Tamil language with a heavy accent’ and ‘are a close-knit group with a heavy cultural background’’.

And for heaven’s sake do not train teachers by telling them that ‘Still the traditional ‘Transmission’ and the ‘Transaction’ roles are prevalent in the classroom. Due to the adverse standard of the school leavers, it has become necessary to develop the learning-teaching process. In the ‘Transmission’ role, the student is considered as someone who does not know anything and the teacher transmits knowledge to him or her. This inhibits the development of the student.

In the ‘Transaction’ role, the dialogue that the teacher starts with the students is the initial stage of this (whatever this might be). Thereafter, from the teacher to the class and from the class to the teacher, ideas flow and interaction between student-student too starts afterwards and turns into a dialogue. From known to unknown, simple to complex are initiated and for this to happen, the teacher starts questioning.’

And while avoiding such tedious jargon, please make sure their command of the language is better than to produce sentences such as these, or what was seen in an English text, again thankfully several years ago:

Read the story …

Hello! We are going to the zoo. “Do you like to join us” asked Sylvia. “Sorry, I can’t I’m going to the library now. Anyway, have a nice time” bye.

So Syliva went to the zoo with her parents. At the entrance her father bought tickets. First, they went to see the monkeys

She looked at a monkey. It made a funny face and started swinging Sylvia shouted: “He is swinging look now it is hanging from its tail its marvellous”

“Monkey usually do that’

I do hope your students will not hang from their tails as these monkeys do.

Midweek Review

Little known composers of classical super-hits

By Satyajith Andradi

Quite understandably, the world of classical music is dominated by the brand images of great composers. It is their compositions that we very often hear. Further, it is their life histories that we get to know. In fact, loads of information associated with great names starting with Beethoven, Bach and Mozart has become second nature to classical music aficionados. The classical music industry, comprising impresarios, music publishers, record companies, broadcasters, critics, and scholars, not to mention composers and performers, is largely responsible for this. However, it so happens that classical music lovers are from time to time pleasantly struck by the irresistible charm and beauty of classical pieces, the origins of which are little known, if not through and through obscure. Intriguingly, most of these musical gems happen to be classical super – hits. This article attempts to present some of these famous pieces and their little-known composers.

Pachelbel’s Canon in D

The highly popular piece known as Pachelbel’s Canon in D constitutes the first part of Johann Pachelbel’s ‘Canon and Gigue in D major for three violins and basso continuo’. The second part of the work, namely the gigue, is rarely performed. Pachelbel was a German organist and composer. He was born in Nuremburg in 1653, and was held in high esteem during his life time. He held many important musical posts including that of organist of the famed St Stephen’s Cathedral in Vienna. He was the teacher of Bach’s elder brother Johann Christoph. Bach held Pachelbel in high regard, and used his compositions as models during his formative years as a composer. Pachelbel died in Nuremburg in 1706.

Pachelbel’s Canon in D is an intricate piece of contrapuntal music. The melodic phrases played by one voice are strictly imitated by the other voices. Whilst the basso continuo constitutes a basso ostinato, the other three voices subject the original tune to tasteful variation. Although the canon was written for three violins and continuo, its immense popularity has resulted in the adoption of the piece to numerous other combinations of instruments. The music is intensely soothing and uplifting. Understandingly, it is widely played at joyous functions such as weddings.

Jeremiah Clarke’s Trumpet Voluntary

The hugely popular piece known as ‘Jeremiah Clarke’s Trumpet Voluntary’ appeared originally as ‘ The Prince of Denmark’s March’ in Jeremiah Clarke’s book ‘ Choice lessons for the Harpsichord and Spinet’, which was published in 1700 ( Michael Kennedy; Oxford Dictionary of Music ). Sometimes, it has also been erroneously attributed to England’s greatest composer Henry Purcell (1659 – 1695 ) and called ‘Purcell’s Trumpet Voluntary (Percy A. Scholes ; Oxford Companion to Music). This brilliant composition is often played at joyous occasions such as weddings and graduation ceremonies. Needless to say, it is a piece of processional music, par excellence. As its name suggests, it is probably best suited for solo trumpet and organ. However, it is often played for different combinations of instruments, with or without solo trumpet. It was composed by the English composer and organist Jeremiah Clarke.

Jeremiah Clarke was born in London in 1670. He was, like his elder contemporary Pachelbel, a musician of great repute during his time, and held important musical posts. He was the organist of London’s St. Paul’s Cathedral and the composer of the Theatre Royal. He died in London in 1707 due to self – inflicted gun – shot injuries, supposedly resulting from a failed love affair.

Albinoni’s Adagio

The full title of the hugely famous piece known as ‘Albinoni’s Adagio’ is ‘Adagio for organ and strings in G minor’. However, due to its enormous popularity, the piece has been arranged for numerous combinations of instruments. It is also rendered as an organ solo. The composition, which epitomizes pathos, is structured as a chaconne with a brooding bass, which reminds of the inevitability and ever presence of death. Nonetheless, there is no trace of despondency in this ethereal music. On the contrary, its intense euphony transcends the feeling of death and calms the soul. The composition has been attributed to the Italian composer Tomaso Albinoni (1671 – 1750), who was a contemporary of Bach and Handel. However, the authorship of the work is shrouded in mystery. Michael Kennedy notes: “The popular Adagio for organ and strings in G minor owes very little to Albinoni, having been constructed from a MS fragment by the twentieth century Italian musicologist Remo Giazotto, whose copyright it is” (Michael Kennedy; Oxford Dictionary of Music).

Boccherini’s Minuet

The classical super-hit known as ‘Boccherini’s Minuet’ is quite different from ‘Albinoni’s Adagio’. It is a short piece of absolutely delightful music. It was composed by the Italian cellist and composer Luigi Boccherini. It belongs to his string quintet in E major, Op. 13, No. 5. However, due to its immense popularity, the minuet is performed on different combinations of instruments.

Boccherini was born in Lucca in 1743. He was a contemporary of Haydn and Mozart, and an elder contemporary of Beethoven. He was a prolific composer. His music shows considerable affinity to that of Haydn. He lived in Madrid for a considerable part of his life, and was attached to the royal court of Spain as a chamber composer. Boccherini died in poverty in Madrid in 1805.

Like numerous other souls, I have found immense joy by listening to popular classical pieces like Pachelbel’s Canon in D, Jeremiah Clarke’s Trumpet Voluntary, Albinoni’s Adagio and Boccherini’s Minuet. They have often helped me to unwind and get over the stresses of daily life. Intriguingly, such music has also made me wonder how our world would have been if the likes of Bach, Handel, Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, and Schubert had never lived. Surely, the world would have been immeasurably poorer without them. However, in all probability, we would have still had Pachelbel’s Canon in D, Jeremiah Clarke’s Trumpet Voluntary, Albinoni’s Adagio, and Boccherini’s Minuet, to cheer us up and uplift our spirits.

Midweek Review

The Tax Payer and the Tough

By Lynn Ockersz

The tax owed by him to Caesar,

Leaves our retiree aghast…

How is he to foot this bill,

With the few rupees,

He has scraped together over the months,

In a shrinking savings account,

While the fires in his crumbling hearth,

Come to a sputtering halt?

But in the suave villa next door,

Stands a hulk in shiny black and white,

Over a Member of the August House,

Keeping an eagle eye,

Lest the Rep of great renown,

Be besieged by petitioners,

Crying out for respite,

From worries in a hand-to-mouth life,

But this thought our retiree horrifies:

Aren’t his hard-earned rupees,

Merely fattening Caesar and his cohorts?