Midweek Review

A philosopher emperor

by Charles Ponnuthurai Sarvan

The titles of books can be misleading. I recall the surprise of a colleague when she saw me carrying a work titled ‘Why is Sex Fun?’ In that book, biologist Jared Diamond explores why human sexual behaviour is so very different from that of animals, even though we are descended from them and still retain some of their behavioural characteristics. The book’s subtitle is ‘The Evolution of Human Sexuality’. The title of Professor Ronald Dworkin’s work, ‘Religion Without God’ (Harvard University Press), seems to be a contradiction, if not an absurdity. Can an atheistic doctrine (the negating particle ‘a’ + theo) be called a religion? But then atheist Einstein said he was religious: “To know that what is impenetrable to us really exists, manifesting itself as the highest wisdom and the most radiant beauty … this knowledge, this feeling, is at the centre of true religiousness. In this sense, and in this sense only, I belong in the ranks of devoutly religious men.” Some have argued that in true Buddhism, that is, as it was preached, there are no gods; even that Buddhism is not a religion but a set of moral precepts and wise, compassionate guidance. So much depends on our definition and concept of terms.

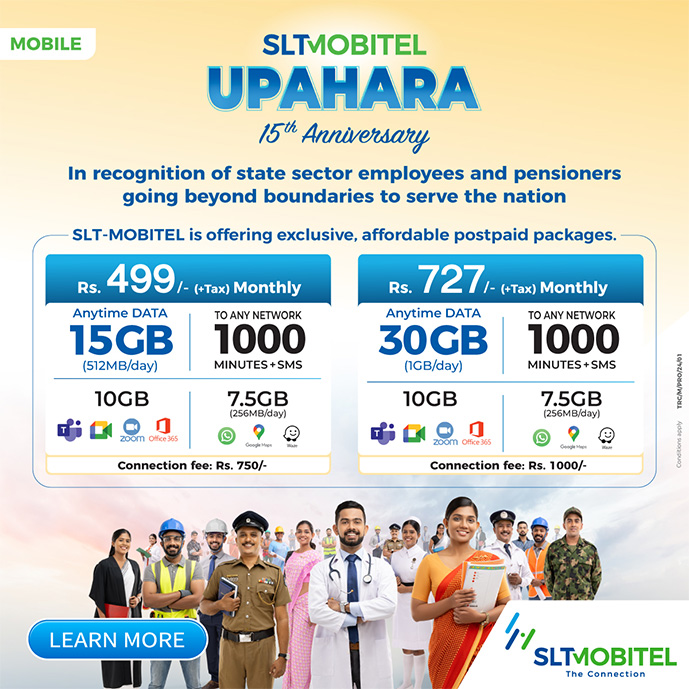

The title of the work that occupies us here, ‘How to Think like a Roman Emperor’ by Donald Robertson (New York, 2019), can initially be misleading. Did all Roman emperors think alike? Not being a Roman emperor, how can I possibly think like one? Again, the book’s subtitle clarifies: ‘The Stoic Philosophy of Marcus Aurelius’. This brings us to Aurelius (121 – 180 CE) and to Stoicism. Admittedly, I have long admired Marcus Aurelius and, to alter words from Ben Jonson, have honoured him “this side of idolatry”. As a note has it, “Marcus Aurelius was the first prominent example of a philosopher king. His Stoic tome ‘Meditations’, written in Greek while on campaign between 170 and 180, is still revered as a literary monument to a philosophy of service and duty, describing how to find and preserve equanimity in the midst of conflict by following nature as a source of guidance and inspiration.”

Socrates, at his trial at which he chose death, said that an unexamined life was not worth living. Aurelius began each morning by thinking about, planning and preparing for the day. The second phase was when he, as emperor, had to act. Finally, at night he reviewed the day and his conduct during it. The ‘Meditations’ was not written for others: it was a kind of “stock taking” of himself, his reactions and behaviour. Aurelius warns himself not to become a Caesar, that is, a dictator. He tried, as far as custom and circumstances permitted, to reduce the pomp which surrounded him (Pope Francis comes to mind) preferring a simple, unpretentious life. As the Greeks knew, we can never see our own face, except by reflection in a mirror. A true friend can act as a mirror, showing us as we really are. Aurelius, therefore, welcomed criticism. Severe on himself, he was patient and kind towards others. As history shows, this extended even to those who had rebelled against him. I wonder if Forster’s comment in his novel, ‘A Passage to India’, that truth is not truth unless spoken gently, derives from the words and example of Marcus Aurelius. Truth, if spoken unkindly, serves only to alienate and antagonise. It may silence the other but does not convince or persuade. In his ‘Meditations’, Aurelius records and rebukes himself when he falls short of the standards he has set himself. The emperor wondered how he could estimate the worth of an individual, and decided it was by seeing to what things that person gave value. In modern terms, it doesn’t mean we must not take an interest in cricket, fashion or food but how much importance and value do we place on such things? Aurelius as emperor couldn’t retreat to his library but had to act. When war broke out on the frontier, he left the safety and comfort of Rome and placed himself at the front with his soldiers. Nor was he solemn and humourless. He is reported to have been good-humoured, affectionate, and close to his family and friends. Before age and responsibilities burdened him, he had hobbies and, as was expected of Roman youths and young men, was active in sports.

At the end, knowing that he was dying; that doctors and medicines couldn’t help, the Emperor calmly and courageously declined food and drink so as not to engage in a futile prolongation of the inevitable. Such an attitude and action are the result of long and serious thought, and preparation: in Shakespeare’s ‘Macbeth’ (Act 1, Scene 4) it’s said of a man that he faced his own execution as one who had “studied” how to die. Aurelius must have known the Latin saying that someone who is not afraid of death cannot be enslaved. Changing time and place, John Donne in a sonnet that begins “Death be not proud” argues that since a person can die only once, having killed him, it’s Death that dies. And in Shakespeare’s ‘Julius Caesar’ (Act 2, Scene 2) Caesar says: “Cowards die many times before their deaths”. As he was dying, Seamus Heaney, winner of the Nobel Prize for Literature, managed to send a text message to his wife in the language he loved, Latin. It consisted of two words: Noli timere (Don’t fear).

Though I am in no way a specialist in either, I am struck by important similarities between Stoicism and Buddhism. For a start, the cornerstone of both is rationality. The Buddha lived from 563 – 483 BCE and Zeno, credited with being the founder of Stoicism, from 334 – 262 BCE. And long before Alexander the Great reached India in 326 BCE, there were links between India and the West. Did Asian Buddhism play a role in the development of Western Stoicism? If research has been done in this area, it has not received publicity: the most effective way of “sinking” a book is to ignore it. Take, for example, Martin Bernal’s thesis in his ‘Black Athena’ that the roots of Western Classical civilization were Afro-Asian. So too, many a male must have been outraged by Martin Stone when he argued in ‘When God was a Woman’ that the first divinities before whom we bowed our heads or prostrated ourselves were female, particularly the ‘mother goddess’. In Sri Lanka, that lucid and refreshing, if radical, work by Dr K S Palihakkara, ‘Buddhism Sans Myths & Miracles’ (Stamford Lake publishers, Pannipitiya) has not excited much, if any, public discussion. Dr Palihakkara’s declared effort was to rescue and cleanse Buddhism from the accretion over time of “myths and miracles and metaphysics”: these took away what was unique to Buddhism, making it more like other religions.

So much of our attitude to life and death depends on our eschatology, our ideas and beliefs about death and the afterlife. The Stoics were atheists believing that at death we disintegrate into and merge with the material, a material which is itself constantly changing. Whether there’s a similarity here with Buddhism, I leave to the reader. The cardinal virtues of Greek philosophy, as of Buddhism, include wisdom (the product of reason and thought), moderation and justice. With Buddhism, it’s not mere verbal and public protestation but actual practice, and so it was with the Stoics. Stoicism was a way of life, assiduously trained in; exemplified by character and conduct.

While in Islam representations of the Prophet are forbidden, Christianity has many paintings and sculptures of Jesus; Jesus with different expression, including pain, even agony. In contrast, the Buddha is almost invariably depicted as being serene. When we lived in Bonn, I used to admire the swans on the Rhine, their sedateness and dignity but, looking more carefully, one saw that these were the result of their feet working constantly, often against the current. So too, the serenity of the Buddha is the result of thought and effort: as is the calm associated with the Stoic.

Anger is temporary madness. Because a deranged person is not controlled by reason, it follows that someone who is angry, someone whose anger is not under control is, for the duration, mad. True Buddhists and Stoics do not give in to anger; they remain detached; free and above this “madness”.

Stoic calmness, the result of mental control, must not be mistaken for emotionlessness. To feel pain and sorrow is human: what counts is our reaction to them. The operative word here is “acceptance”. Sorrow, while it has its impact on us, must be met with wisdom; pain, with acceptance. (Related to acceptance is the key term and concept of relinquishment.) Thorns hurt, and the Bible advises us not to increase the pain by kicking against them. The Stoic image was of a dog tied to a cart: the dog can either walk along or make things worse for itself by struggling, futilely and painfully. A 20th century philosopher asked for the courage to change those things which can be changed; the serenity to accept what can’t be altered, and the wisdom to know the difference. Donald Robertson, a cognitive-behavioural psychotherapist, brings in modern terms and concepts to an understanding of Marcus Aurelius, among them the Stoic reserve-clause. Our expectations are ‘reserved’ for what is within our sphere of control: the rest is up to chance or, as believers would say, “Deo volente” or “Deo gratis”. (When I asked a friend why he often said “Inshallah” though he had never been a Muslim and was in fact a thorough atheist, he replied that it was in a philosophical and not in a religious sense: “If my effort and chance will it”.) As with emotions, so with our desires: of importance to the Stoics was (a) what we desired; (b) to what degree, and (c) how we set about achieving these desires.

Central to Buddhism and Stoicism is an awareness of transience, known in the former as “Anicca”. Heraclitus (500 BCE) famously declared that all is flux. We cannot step into the same river twice because fresh waters are ever flowing in. For better or worse, we are not the same as we were several, or even a few, years ago. We change, others change, relationships change, the world around us changes. All is flux. And as T S Eliot, borrowing from Hinduism, writes in ‘Murder in the Cathedral’, only a fool fixed in his folly thinks he can turn the wheel on which he turns.

I read that there’s a tribe which mourns birth and celebrates death, and Shakespeare in his major tragedy ‘King Lear’ suggests with ironic wit that all infants cry when they are born because they have come to this world! Freud suggested that in as much as we have an instinct for preservation and survival, there can also be a wish for death, for a return to a previous state of non-existence: see terms such as ‘Todestriebe’ and ‘Thanatos’. James Thomson in his poem, ‘City of Dreadful Night’ writes:

This little life is all we must endure,

The grave’s most holy peace is ever sure,

We fall asleep and never wake again;

Nothing is of us but the mouldering flesh,

Whose elements dissolve and merge afresh…

“And the cessation / of life’s peacock scream / will be relief” (Liebetraut Sarvan).

In Book 1 of his ‘Histories’, Herodotus relates the story of a mother who, full of love for and pride in her two sons, prays in the evening to the goddess Hera that she bestows on them “the greatest blessing” that can fall on mortals. The goddess answers the prayer, and the young men are found in the morning – dead. Diagones (412 – 323 BCE) who had a sharp sense of ‘humour’ requested that his dead body be thrown over the city walls so that the wild animals could have a meal: no longer having consciousness, what was done to his body didn’t matter. Respect for a corpse; gravestones and monuments; memorial services, prayers and rituals are for the living, and not for the dead. Buddhist nirvana means the final deliverance from suffering and sorrow: an escape into freedom effected by ceasing to be.

Given these conceptions of life and death, it is not surprising that suicide (not on impulse; not in despair or in a state of temporary madness) was accepted; indeed, in certain situations it was admired and highly honoured. Shakespeare’s Hamlet contemplating suicide and the “sleep” that follows it, saw death as a “consummation” devoutly to be wished for. Each individual must decide, with utmost clarity and calmness “whether the time is come to take leave of life” (‘Meditations’, Book 3). Or as Aurelius expresses it elsewhere, the chimney smokes and I leave the room (Book 5). To the Stoics, lamentation at death was for the loss that the living experienced, and not for the departed:

No motion has she now, no force

She neither hears nor sees;

Rolled round in earth’s diurnal course With rocks, and stones, and trees

(William Wordsworth)

Bertrand Russell (1872 – 1970) wrote: “I should scorn to shiver with terror at the thought of annihilation. Happiness is nonetheless true happiness because it must come to an end, nor do thought and love lose their value because they are not everlasting. Many a man has borne himself proudly on the scaffold; surely the same pride should teach us to think truly about man’s place in the world.” And so I return to the serenity of the Buddha and to the calm of Stoicism: the aim of both was (through rational thought and conscious, controlled, behaviour) to minimise pain and to increase peace and happiness. Both Buddhism and Stoicism are positive and life-enhancing.

Addendum.

I draw attention to what I wrote in ‘Colombo Telegraph’ (1 February 2018) under the caption ‘Religious doctrine and religion’. If we say that Christianity is a gentle, or Buddhism a compassionate, religion what we mean is these faiths as they were taught – most certainly, not as they are practiced in private and public life. I suggested a distinction between religious doctrine and religion with its rituals, paraphernalia, hierarchy, myths and superstitions. Religious doctrine has a divine or semi-divine origin or is from an exalted, exceptional, individual. Simplifying, one could say: “Religious doctrine is ‘divine’ but religion is a human construct”.

- News Advertiesment

See Kapruka’s top selling online shopping categories such as Toys, Grocery, Flowers, Birthday Cakes, Fruits, Chocolates, Clothing and Electronics. Also see Kapruka’s unique online services such as Money Remittence,News, Courier/Delivery, Food Delivery and over 700 top brands. Also get products from Amazon & Ebay via Kapruka Gloabal Shop into Sri Lanka.

Midweek Review

‘Professor of English Language Teaching’

It is a pleasure to be here today, when the University resumes postgraduate work in English and Education which we first embarked on over 20 years ago. The presence of a Professor on English Language Teaching from Kelaniya makes clear that the concept has now been mainstreamed, which is a cause for great satisfaction.

Twenty years ago, this was not the case. Our initiative was looked at askance, as indeed was the initiative which Prof. Arjuna Aluwihare engaged in as UGC Chairman to make degrees in English more widely available. Those were the days in which the three established Departments of English in the University system, at Peradeniya and Kelaniya and Colombo, were unbelievably conservative. Their contempt for his efforts made him turn to Sri Jayewardenepura, which did not even have a Department of English then and only offered it as one amongst three subjects for a General Degree.

Twenty years ago, this was not the case. Our initiative was looked at askance, as indeed was the initiative which Prof. Arjuna Aluwihare engaged in as UGC Chairman to make degrees in English more widely available. Those were the days in which the three established Departments of English in the University system, at Peradeniya and Kelaniya and Colombo, were unbelievably conservative. Their contempt for his efforts made him turn to Sri Jayewardenepura, which did not even have a Department of English then and only offered it as one amongst three subjects for a General Degree.

Ironically, the most dogmatic defence of this exclusivity came from Colombo, where the pioneer in English teaching had been Prof. Chitra Wickramasuriya, whose expertise was, in fact, in English teaching. But her successor, when I tried to suggest reforms, told me proudly that their graduates could go on to do postgraduate degrees at Cambridge. I suppose that, for generations brought up on idolization of E. F. C. Ludowyke, that was the acme of intellectual achievement.

I should note that the sort of idealization of Ludowyke, the then academic establishment engaged in was unfair to a very broadminded man. It was the Kelaniya establishment that claimed that he ‘maintained high standards, but was rarefied and Eurocentric and had an inhibiting effect on creative writing’. This was quite preposterous coming from someone who removed all Sri Lankan and other post-colonial writing from an Advanced Level English syllabus. That syllabus, I should mention, began with Jacobean poetry about the cherry-cheeked charms of Englishwomen. And such a characterization of Ludowyke totally ignored his roots in Sri Lanka, his work in drama which helped Sarachchandra so much, and his writing including ‘Those Long Afternoons’, which I am delighted that a former Sabaragamuwa student, C K Jayanetti, hopes to resurrect.

I have gone at some length into the situation in the nineties because I notice that your syllabus includes in the very first semester study of ‘Paradigms in Sri Lankan English Education’. This is an excellent idea, something which we did not have in our long-ago syllabus. But that was perhaps understandable since there was little to study then except a history of increasing exclusivity, and a betrayal of the excuse for getting the additional funding those English Departments received. They claimed to be developing teachers of English for the nation; complete nonsense, since those who were knowledgeable about cherries ripening in a face were not likely to move to rural areas in Sri Lanka to teach English. It was left to the products of Aluwihare’s initiative to undertake that task.

Another absurdity of that period, which seems so far away now, was resistance to training for teaching within the university system. When I restarted English medium education in the state system in Sri Lanka, in 2001, and realized what an uphill struggle it was to find competent teachers, I wrote to all the universities asking that they introduce modules in teacher training. I met condign refusal from all except, I should note with continuing gratitude, from the University of Sri Jayewardenepura, where Paru Nagasunderam introduced it for the external degree. When I started that degree, I had taken a leaf out of Kelaniya’s book and, in addition to English Literature and English Language, taught as two separate subjects given the language development needs of students, made the third subject Classics. But in time I realized that was not at all useful. Thankfully, that left a hole which ELT filled admirably at the turn of the century.

The title of your keynote speaker today, Professor of English Language Teaching, is clear evidence of how far we have come from those distant days, and how thankful we should be that a new generation of practical academics such as her and Dinali Fernando at Kelaniya, Chitra Jayatilleke and Madhubhashini Ratnayake at USJP and the lively lot at the Postgraduate Institute of English at the Open University are now making the running. I hope Sabaragamuwa under its current team will once again take its former place at the forefront of innovation.

To get back to your curriculum, I have been asked to teach for the paper on Advanced Reading and Writing in English. I worried about this at first since it is a very long time since I have taught, and I feel the old energy and enthusiasm are rapidly fading. But having seen the care with which the syllabus has been designed, I thought I should try to revive my flagging capabilities.

However, I have suggested that the university prescribe a textbook for this course since I think it is essential, if the rounded reading prescribed is to be done, that students should have ready access to a range of material. One of the reasons I began while at the British Council an intensive programme of publications was that students did not read round their texts. If a novel was prescribed, they read that novel and nothing more. If particular poems were prescribed, they read those poems and nothing more. This was especially damaging in the latter case since the more one read of any poet the more one understood what he was expressing.

Though given the short notice I could not prepare anything, I remembered a series of school textbooks I had been asked to prepare about 15 years ago by International Book House for what were termed international schools offering the local syllabus in the English medium. Obviously, the appalling textbooks produced by the Ministry of Education in those days for the rather primitive English syllabus were unsuitable for students with more advanced English. So, I put together more sophisticated readers which proved popular. I was heartened too by a very positive review of these by Dinali Fernando, now at Kelaniya, whose approach to students has always been both sympathetic and practical.

I hope then that, in addition to the texts from the book that I will discuss, students will read other texts in the book. In addition to poetry and fiction the book has texts on politics and history and law and international relations, about which one would hope postgraduate students would want some basic understanding.

Similarly, I do hope whoever teaches about Paradigms in English Education will prescribe a textbook so that students will understand more about what has been going on. Unfortunately, there has been little published about this but at least some students will I think benefit from my book on English and Education: In Search of Equity and Excellence? which Godage & Bros brought out in 2016. And then there was Lakmahal Justified: Taking English to the People, which came out in 2018, though that covers other topics too and only particular chapters will be relevant.

The former book is bulky but I believe it is entertaining as well. So, to conclude I will quote from it, to show what should not be done in Education and English. For instance, it is heartening that you are concerned with ‘social integration, co-existence and intercultural harmony’ and that you want to encourage ‘sensitivity towards different cultural and linguistic identities’. But for heaven’s sake do not do it as the NIE did several years ago in exaggerating differences. In those dark days, they produced textbooks which declared that ‘Muslims are better known as heavy eaters and have introduced many tasty dishes to the country. Watalappam and Buriani are some of these dishes. A distinguished feature of the Muslims is that they sit on the floor and eat food from a single plate to show their brotherhood. They eat string hoppers and hoppers for breakfast. They have rice and curry for lunch and dinner.’ The Sinhalese have ‘three hearty meals a day’ and ‘The ladies wear the saree with a difference and it is called the Kandyan saree’. Conversely, the Tamils ‘who live mainly in the northern and eastern provinces … speak the Tamil language with a heavy accent’ and ‘are a close-knit group with a heavy cultural background’’.

And for heaven’s sake do not train teachers by telling them that ‘Still the traditional ‘Transmission’ and the ‘Transaction’ roles are prevalent in the classroom. Due to the adverse standard of the school leavers, it has become necessary to develop the learning-teaching process. In the ‘Transmission’ role, the student is considered as someone who does not know anything and the teacher transmits knowledge to him or her. This inhibits the development of the student.

In the ‘Transaction’ role, the dialogue that the teacher starts with the students is the initial stage of this (whatever this might be). Thereafter, from the teacher to the class and from the class to the teacher, ideas flow and interaction between student-student too starts afterwards and turns into a dialogue. From known to unknown, simple to complex are initiated and for this to happen, the teacher starts questioning.’

And while avoiding such tedious jargon, please make sure their command of the language is better than to produce sentences such as these, or what was seen in an English text, again thankfully several years ago:

Read the story …

Hello! We are going to the zoo. “Do you like to join us” asked Sylvia. “Sorry, I can’t I’m going to the library now. Anyway, have a nice time” bye.

So Syliva went to the zoo with her parents. At the entrance her father bought tickets. First, they went to see the monkeys

She looked at a monkey. It made a funny face and started swinging Sylvia shouted: “He is swinging look now it is hanging from its tail its marvellous”

“Monkey usually do that’

I do hope your students will not hang from their tails as these monkeys do.

Midweek Review

Little known composers of classical super-hits

By Satyajith Andradi

Quite understandably, the world of classical music is dominated by the brand images of great composers. It is their compositions that we very often hear. Further, it is their life histories that we get to know. In fact, loads of information associated with great names starting with Beethoven, Bach and Mozart has become second nature to classical music aficionados. The classical music industry, comprising impresarios, music publishers, record companies, broadcasters, critics, and scholars, not to mention composers and performers, is largely responsible for this. However, it so happens that classical music lovers are from time to time pleasantly struck by the irresistible charm and beauty of classical pieces, the origins of which are little known, if not through and through obscure. Intriguingly, most of these musical gems happen to be classical super – hits. This article attempts to present some of these famous pieces and their little-known composers.

Pachelbel’s Canon in D

The highly popular piece known as Pachelbel’s Canon in D constitutes the first part of Johann Pachelbel’s ‘Canon and Gigue in D major for three violins and basso continuo’. The second part of the work, namely the gigue, is rarely performed. Pachelbel was a German organist and composer. He was born in Nuremburg in 1653, and was held in high esteem during his life time. He held many important musical posts including that of organist of the famed St Stephen’s Cathedral in Vienna. He was the teacher of Bach’s elder brother Johann Christoph. Bach held Pachelbel in high regard, and used his compositions as models during his formative years as a composer. Pachelbel died in Nuremburg in 1706.

Pachelbel’s Canon in D is an intricate piece of contrapuntal music. The melodic phrases played by one voice are strictly imitated by the other voices. Whilst the basso continuo constitutes a basso ostinato, the other three voices subject the original tune to tasteful variation. Although the canon was written for three violins and continuo, its immense popularity has resulted in the adoption of the piece to numerous other combinations of instruments. The music is intensely soothing and uplifting. Understandingly, it is widely played at joyous functions such as weddings.

Jeremiah Clarke’s Trumpet Voluntary

The hugely popular piece known as ‘Jeremiah Clarke’s Trumpet Voluntary’ appeared originally as ‘ The Prince of Denmark’s March’ in Jeremiah Clarke’s book ‘ Choice lessons for the Harpsichord and Spinet’, which was published in 1700 ( Michael Kennedy; Oxford Dictionary of Music ). Sometimes, it has also been erroneously attributed to England’s greatest composer Henry Purcell (1659 – 1695 ) and called ‘Purcell’s Trumpet Voluntary (Percy A. Scholes ; Oxford Companion to Music). This brilliant composition is often played at joyous occasions such as weddings and graduation ceremonies. Needless to say, it is a piece of processional music, par excellence. As its name suggests, it is probably best suited for solo trumpet and organ. However, it is often played for different combinations of instruments, with or without solo trumpet. It was composed by the English composer and organist Jeremiah Clarke.

Jeremiah Clarke was born in London in 1670. He was, like his elder contemporary Pachelbel, a musician of great repute during his time, and held important musical posts. He was the organist of London’s St. Paul’s Cathedral and the composer of the Theatre Royal. He died in London in 1707 due to self – inflicted gun – shot injuries, supposedly resulting from a failed love affair.

Albinoni’s Adagio

The full title of the hugely famous piece known as ‘Albinoni’s Adagio’ is ‘Adagio for organ and strings in G minor’. However, due to its enormous popularity, the piece has been arranged for numerous combinations of instruments. It is also rendered as an organ solo. The composition, which epitomizes pathos, is structured as a chaconne with a brooding bass, which reminds of the inevitability and ever presence of death. Nonetheless, there is no trace of despondency in this ethereal music. On the contrary, its intense euphony transcends the feeling of death and calms the soul. The composition has been attributed to the Italian composer Tomaso Albinoni (1671 – 1750), who was a contemporary of Bach and Handel. However, the authorship of the work is shrouded in mystery. Michael Kennedy notes: “The popular Adagio for organ and strings in G minor owes very little to Albinoni, having been constructed from a MS fragment by the twentieth century Italian musicologist Remo Giazotto, whose copyright it is” (Michael Kennedy; Oxford Dictionary of Music).

Boccherini’s Minuet

The classical super-hit known as ‘Boccherini’s Minuet’ is quite different from ‘Albinoni’s Adagio’. It is a short piece of absolutely delightful music. It was composed by the Italian cellist and composer Luigi Boccherini. It belongs to his string quintet in E major, Op. 13, No. 5. However, due to its immense popularity, the minuet is performed on different combinations of instruments.

Boccherini was born in Lucca in 1743. He was a contemporary of Haydn and Mozart, and an elder contemporary of Beethoven. He was a prolific composer. His music shows considerable affinity to that of Haydn. He lived in Madrid for a considerable part of his life, and was attached to the royal court of Spain as a chamber composer. Boccherini died in poverty in Madrid in 1805.

Like numerous other souls, I have found immense joy by listening to popular classical pieces like Pachelbel’s Canon in D, Jeremiah Clarke’s Trumpet Voluntary, Albinoni’s Adagio and Boccherini’s Minuet. They have often helped me to unwind and get over the stresses of daily life. Intriguingly, such music has also made me wonder how our world would have been if the likes of Bach, Handel, Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, and Schubert had never lived. Surely, the world would have been immeasurably poorer without them. However, in all probability, we would have still had Pachelbel’s Canon in D, Jeremiah Clarke’s Trumpet Voluntary, Albinoni’s Adagio, and Boccherini’s Minuet, to cheer us up and uplift our spirits.

Midweek Review

The Tax Payer and the Tough

By Lynn Ockersz

The tax owed by him to Caesar,

Leaves our retiree aghast…

How is he to foot this bill,

With the few rupees,

He has scraped together over the months,

In a shrinking savings account,

While the fires in his crumbling hearth,

Come to a sputtering halt?

But in the suave villa next door,

Stands a hulk in shiny black and white,

Over a Member of the August House,

Keeping an eagle eye,

Lest the Rep of great renown,

Be besieged by petitioners,

Crying out for respite,

From worries in a hand-to-mouth life,

But this thought our retiree horrifies:

Aren’t his hard-earned rupees,

Merely fattening Caesar and his cohorts?