Midweek Review

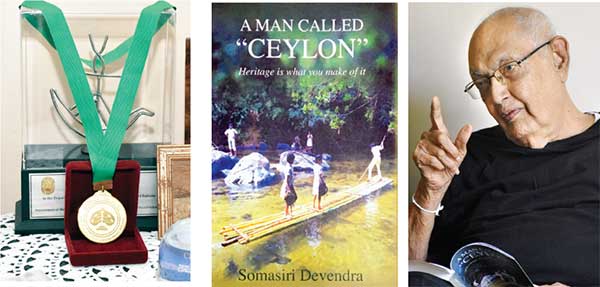

Call of the sea From Navy to maritime archaeologist, Somasiri Devendra comes full circle

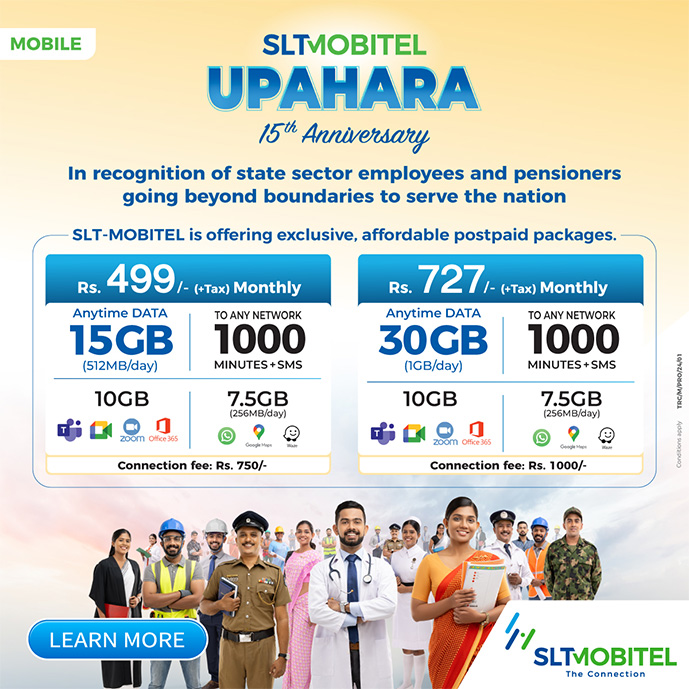

‘A Man Called ‘Ceylon” by Somasiri Devendra now available in all leading bookshops

By Sajitha Prematunge

The title ‘A Man Called ‘Ceylon” derives from the sea-faring days of his maternal grandfather, Lloyd Aswald, who was referred to as ‘Ceylon’ by his shipmates in whichever ship he sailed in, because he was always the only Ceylonese on board. In fact, his penchant for all things water-related, from sunken archaeological treasures to vernacular watercraft, Somasiri Devendra admits, may have been inspired by his grandfather.

Although a book about watercraft, ‘A man called ‘Ceylon” does not run the risk of reading like a research paper, and as the writer himself admits in one chapter, is rather a narrative. It is by no means heady with technical jargon, and is quite readable even for those who haven’t the slightest interest in ships.

His ‘Yesterday is Another Country’ is a collection of autobiographical short stories and he edited his father’s notes about his childhood into ‘The Way We Grew’. But his personal favourite is ‘Two to Tango’, because it is intensely personal, being about his first time living in a village between age 11 and 14. ‘We must have a Navy’ never hit the bookshops because the publishing was undertaken by SL Navy and was sold out within the navy itself. He admits that ‘From Wooden Walls to Ironclads’ was a labour of love.

The book

The articles he wrote to various newspapers between books have been collected in his latest ‘A Man Called ‘Ceylon”. According to the Forward, the reminiscences, investigations and fantasies had been written, at different times for readers of different ages. Most of the chapters being individual articles previously published, are standalone stories in their own right and could easily be enjoyed even out of context. The book is divided roughly into two parts. The first half, ‘Waterways and Watercraft’, draws upon Devendra’s mother’s awakening of ‘the watery element’ in him. The second half of the book ‘Heritage and History’ is his father’s legacy. “Some of them are serious, some great adventures,” said Devendra, the passage titled VVT Tahiti & The Ghost of the Bounty for example. Devendra admits that the voyage of discovery took many years to put together.

VVT Tahiti & The Ghost of the Bounty is about a ship built in Jaffna, originally named ‘Annapooranymal’ and later renamed Florence C. Robinson known as a ‘tidy little vessel, built of honest workmanship and good hard-wood’ that withstood hurricanes and doldrums, fire in the galley, shredded sails, broken bilge pumps and a malfunctioning auxiliary engine. And where’s the adventure without a ‘man overboard’ scare! She was sailed by an all Jaffna crew from Valvettithurai to Boston, US. “It is the longest voyage made by a sailing ship at the time. It was last recorded to have been used in the copra trade and no further information has surfaced since then,” said Devendra.

It is all the more intriguing due to the fact that it was quite similar in design to HMS Bounty of the Mutiny on the Bounty fame. According to Devendra, it was not entirely home-grown and may also have been heavily influenced by South Indian ship building technology at the time. “There were Indo-Arab boats as well.” The fully home-grown version was the Yathra Dhoni or Maha Oruwa, last of which was Amugoda Oruwa, which perished on a reef off Male, according to the chapter ‘The Mansions of the Sea’. Each of these watercraft types have been meticulously detailed in the book. Devendra surmised that the vernacular tradition was pre-Vijayan, which originated in the forested region with large rivers in the South-West of the country.

His expertise of the watercraft is evident throughout the narrative peppered with nautical lingo such as ”Seventy-five to hundred foot freighters…rigged with jib, main and mizzen sails, rudder and a sturdy outrigger’, ‘…schooner-rigged two-master, 89′ on deck, with a 33′ jib boom…beam of 19′ and a draught of only 8’, ‘greater beam and draft…fully rigged…not a Frigate but a converted Collier…fitted with an auxiliary (50 HP Belinda Marine) engine’, so on and so forth. It may sound like gibberish to the layman, but all this talk of sunken, marooned and altogether missing ships is strangely reminiscent of the ‘The Ghost from the Grand Banks’, the 1990 science fiction novel by Sir Arthur C. Clarke. It makes one wonder if Devendra and the underwater explorer in Clarke would have hit it off instantly, had they been acquainted.

The book as a whole is a pleasurable read, notwithstanding a few typos. Even the little anecdotes that deviate completely from the main story, such as that of one-time skipper of Florence C, Sterling Hayden, who went from being a high school drop out, fisherman, ship mate, Hollywood sweetheart, to decorated war hero and finally writer, is quite intriguing. The Gujarati lore about the Ceylonese bride and the Gujarati prince is another interesting anecdote, retold in ‘The Other Princess Padma’. As the Gujarati saying goes, ‘Like a bride from Ceylon and a groom from Gujarat’, a Ceylonese princess winds up marrying a Gujarati prince, despite the Princess’ father’s best efforts to prevent it. The old WW II story, ‘The Surrender’, of how an Italian warship surrendered to Ceylonese Navy, has been sourced from an old Navy veteran. The Italian government had decided to surrender by then and all its naval units have been ordered to turn themselves into the nearest Allied Forces. It was a historic event, despite the uneventful surrender.

In ‘The Island of Fate’ Devendra explores the irksome possibility that disciplining in the colonial era depended on colour. The Cocos Island mutineers, the only dissenters who were executed, who all happened to be Ceylonese, was a case in point. A contingent of Ceylon Garrison Artillery was posted to Cocos Island off Australia in September 1939, when Britain declared war on Nazi Germany. They mutinied and were duly executed. The investigation undertaken by journalist Noel Crusz culminated in 2001 in the book ‘The Cocos Islands Mutiny’. Devendra has placed it in the socio-economic context of Sri Lanka at the time.

Devendra retired from the Navy in 1976, but duty called 20 years later during the war. The Chapter ‘The Forests of the Night’ is the culmination of his service in the Navy during Operation Riviresa as the Deputy Commandant of a volunteer force with a very specific goal. “Riviresa was launched with the objective of retaking Jaffna.” Devendra, et al, were tasked with raising a corps of approximately 10,000 volunteers to send to the Eastern Front, to relieve regular troops so they could be retasked in the North, a quixotic scheme he admits, with more gung-ho than common sense. After much cajoling and promises of honour, they ended up with half the number of volunteers they needed. With only three weeks left for training, the only guns available to them to train with were World War II .303 rifles and factory rejects for uniforms. But the quixotic operation, held together by a ‘string and a prayer’ actually worked and in six months Jaffna was retaken, all without losing a single volunteer.

Devendra hypothesises that the local sense of respect for trees derives from our pre-Buddhist animistic culture and an impetus was provided by the gratitude the Buddha expressed to the Bo tree. The passage ‘Caring for a tree’ explores this symbiotic relationship with trees. In it he describes how his inquisitiveness led him to discover a tombstone-like upright stone slab by the Wellawatta bridge, with indiscernible writing. As it turned out, the slab had been erected by one Sophia Marshall in 1820, before Ceylon was even a crown colony, in gratitude of a banyan tree. Perhaps she was an earlier day ‘ruk rekaganna’, mused Devendra. “What’s amazing is that someone went to the trouble of getting it carved and erected there.”

Sophia nee Brooke, daughter of St. Helena Governor, Col. Robert Brooke, married Henry Augustus Marshall and moved to Ceylon in 1798. The Banyan tree as well as Sophia is long gone but it is rather ironic that her ‘so human act of caring’ is etched in lifeless stone thus;

“To him whose gracious aim in mercy bends,

And light and shade to all alike extends,

Who guards the traveler of his weary way,

Shelters from storm and shades from solar ray,

Breathe one kind wish for her, one Pious prayer,

Who made this sheltering tree her guardian care,

Fenced in from rude attacks the pendent shoots,

Nourished and framed its tender, infant shoots,

Traveler, if from milder climes you rove

How dearly will you prize this Indian grove.

Pause then, awhile, and ere you ass it by,

Give to Sophia’s name one grateful sigh.

A.D. 1820″

The intensely visual imagery in the narrative of ‘A Man Called ‘Ceylon”, ‘full bellied sails’, for example, is reminiscent of his brother, Tissa Devendra’s accounts of a bygone age in ‘On Horseshoe Street: More Tales from the Provinces’, although the junior Devendra admits considerable differences in their writing style. Literary talents obviously run in the family and everyone concedes that Ransiri Menike Silva, the younger sister is by far the most prolific. Although the Devendras were, as they say, ‘English educated’, had a good taste of the village life. This is evident in their collective writings, in the authenticity of descriptions on village life, from Tissa’s ‘On Horseshoe Street’, Ransiri Menike Silva’s Worm’s Eye View to Somasiri Devendra’s ‘A man called ‘Ceylon” itself.

The man

Devendra, in his own words, is the ‘proverbial rolling stone’, a man of many talents who cannot seem to sit idle. A graduate of the first batch of University of Ceylon, now Peradeniya University, in 1955, he was a school teacher before being commissioned an Instructor Officer in the then Royal Ceylon Navy in 1960 and wound up a Commandant, Naval & Maritime Academy, Trincomalee.

Much like his brother, Tissa and sister, Ransiri Menike, who started taking writing seriously only in her 40s but went on to clinch the State Literary Award, Somasiri Devendra found his calling, archaeology, after retirement, first from the Navy, after 17 years of service, then an illustrious career as a company director. Soon after leaving the Navy and joining Somerville & Co. Ltd., Sri Lanka’s oldest firm of Share and Produce Brokers, Devendra climbed up the corporate ladder to make director. He was also a founding Director of the then fledgling Colombo Stock Exchange. “The adventures of the mercantile forest ultimately gave me heart trouble,” said Devendra.

The resourceful man that he is, Devendra did not want to spend the rest of his life idling. Consequently, he decided to take up the investigation of local maritime heritage as a full-time occupation. Few would believe that a career change at 55 is feasible, but not for Devendra, who, as a child, used to tag along with his archaeologist father, D.T. Devendra, on his excursions in search of ruins in the jungle. He defines the period after retirement, as the most fruitful period of his life. In addition to dabbling with archaeology for the first time, he wrote prolifically, anything from books to feature article to the paper.

“I started attending international conferences on archaeology of my own volition and meeting people from different parts of the world was interesting.” Devendra noted that, unlike people from most other countries, as a people, Sri Lankans were more aware of our own heritage. A pariah in the field of archaeology, notwithstanding his father’s legacy, Devendra wasn’t exactly welcomed with open arms. All the government institutions wanted him, because they recognised the fact that he could get things done, but couldn’t technically offer him a job, because he was over 55.

“I didn’t represent any university department, and funding restrictions were to be expected,” said Devendra. Luckily foreign institutions took note and invited him to more conferences, some even offering funding. His fascination with archaeology lead him to the most unexpected places such as Jamaica, Mozambique, Hawaii, Taiwan and Germany.

But he caught his biggest break while training a student group for the Post Graduate Institute of Archaeology on underwater archaeology, in Galle, with the help of an Australian maritime museum. “The Australian trainers, who happened to have a lot of time on their hands, discovered that the Galle harbour was strewn with shipwrecks, so why not investigate they suggested,” said Devendra. He readily complied. Between 1992 and 1994, the project continued on a shoestring budget, until Minister of Cultural Affairs Lakshman Jayakody visited Galle, was impressed with the project, asked around for a point man, was directed to Devendra and later called in with an offer of funding. “It was several millions and a lot more than we could hope to squeeze out of any government department’s accounts division!” chuckled Devendra. A project plan was drawn up by Devendra and by the time the money was passed, they already had a team in place, and the money was utilised to buy much needed equipment.

From the Navy to corporate director and finally maritime archaeologist read how this multifaceted man came full circle, in ‘A Man Called ‘Ceylon”.

Pics by Kamal Wanniarachchi

- News Advertiesment

See Kapruka’s top selling online shopping categories such as Toys, Grocery, Flowers, Birthday Cakes, Fruits, Chocolates, Clothing and Electronics. Also see Kapruka’s unique online services such as Money Remittence,News, Courier/Delivery, Food Delivery and over 700 top brands. Also get products from Amazon & Ebay via Kapruka Gloabal Shop into Sri Lanka.

Midweek Review

‘Professor of English Language Teaching’

It is a pleasure to be here today, when the University resumes postgraduate work in English and Education which we first embarked on over 20 years ago. The presence of a Professor on English Language Teaching from Kelaniya makes clear that the concept has now been mainstreamed, which is a cause for great satisfaction.

Twenty years ago, this was not the case. Our initiative was looked at askance, as indeed was the initiative which Prof. Arjuna Aluwihare engaged in as UGC Chairman to make degrees in English more widely available. Those were the days in which the three established Departments of English in the University system, at Peradeniya and Kelaniya and Colombo, were unbelievably conservative. Their contempt for his efforts made him turn to Sri Jayewardenepura, which did not even have a Department of English then and only offered it as one amongst three subjects for a General Degree.

Twenty years ago, this was not the case. Our initiative was looked at askance, as indeed was the initiative which Prof. Arjuna Aluwihare engaged in as UGC Chairman to make degrees in English more widely available. Those were the days in which the three established Departments of English in the University system, at Peradeniya and Kelaniya and Colombo, were unbelievably conservative. Their contempt for his efforts made him turn to Sri Jayewardenepura, which did not even have a Department of English then and only offered it as one amongst three subjects for a General Degree.

Ironically, the most dogmatic defence of this exclusivity came from Colombo, where the pioneer in English teaching had been Prof. Chitra Wickramasuriya, whose expertise was, in fact, in English teaching. But her successor, when I tried to suggest reforms, told me proudly that their graduates could go on to do postgraduate degrees at Cambridge. I suppose that, for generations brought up on idolization of E. F. C. Ludowyke, that was the acme of intellectual achievement.

I should note that the sort of idealization of Ludowyke, the then academic establishment engaged in was unfair to a very broadminded man. It was the Kelaniya establishment that claimed that he ‘maintained high standards, but was rarefied and Eurocentric and had an inhibiting effect on creative writing’. This was quite preposterous coming from someone who removed all Sri Lankan and other post-colonial writing from an Advanced Level English syllabus. That syllabus, I should mention, began with Jacobean poetry about the cherry-cheeked charms of Englishwomen. And such a characterization of Ludowyke totally ignored his roots in Sri Lanka, his work in drama which helped Sarachchandra so much, and his writing including ‘Those Long Afternoons’, which I am delighted that a former Sabaragamuwa student, C K Jayanetti, hopes to resurrect.

I have gone at some length into the situation in the nineties because I notice that your syllabus includes in the very first semester study of ‘Paradigms in Sri Lankan English Education’. This is an excellent idea, something which we did not have in our long-ago syllabus. But that was perhaps understandable since there was little to study then except a history of increasing exclusivity, and a betrayal of the excuse for getting the additional funding those English Departments received. They claimed to be developing teachers of English for the nation; complete nonsense, since those who were knowledgeable about cherries ripening in a face were not likely to move to rural areas in Sri Lanka to teach English. It was left to the products of Aluwihare’s initiative to undertake that task.

Another absurdity of that period, which seems so far away now, was resistance to training for teaching within the university system. When I restarted English medium education in the state system in Sri Lanka, in 2001, and realized what an uphill struggle it was to find competent teachers, I wrote to all the universities asking that they introduce modules in teacher training. I met condign refusal from all except, I should note with continuing gratitude, from the University of Sri Jayewardenepura, where Paru Nagasunderam introduced it for the external degree. When I started that degree, I had taken a leaf out of Kelaniya’s book and, in addition to English Literature and English Language, taught as two separate subjects given the language development needs of students, made the third subject Classics. But in time I realized that was not at all useful. Thankfully, that left a hole which ELT filled admirably at the turn of the century.

The title of your keynote speaker today, Professor of English Language Teaching, is clear evidence of how far we have come from those distant days, and how thankful we should be that a new generation of practical academics such as her and Dinali Fernando at Kelaniya, Chitra Jayatilleke and Madhubhashini Ratnayake at USJP and the lively lot at the Postgraduate Institute of English at the Open University are now making the running. I hope Sabaragamuwa under its current team will once again take its former place at the forefront of innovation.

To get back to your curriculum, I have been asked to teach for the paper on Advanced Reading and Writing in English. I worried about this at first since it is a very long time since I have taught, and I feel the old energy and enthusiasm are rapidly fading. But having seen the care with which the syllabus has been designed, I thought I should try to revive my flagging capabilities.

However, I have suggested that the university prescribe a textbook for this course since I think it is essential, if the rounded reading prescribed is to be done, that students should have ready access to a range of material. One of the reasons I began while at the British Council an intensive programme of publications was that students did not read round their texts. If a novel was prescribed, they read that novel and nothing more. If particular poems were prescribed, they read those poems and nothing more. This was especially damaging in the latter case since the more one read of any poet the more one understood what he was expressing.

Though given the short notice I could not prepare anything, I remembered a series of school textbooks I had been asked to prepare about 15 years ago by International Book House for what were termed international schools offering the local syllabus in the English medium. Obviously, the appalling textbooks produced by the Ministry of Education in those days for the rather primitive English syllabus were unsuitable for students with more advanced English. So, I put together more sophisticated readers which proved popular. I was heartened too by a very positive review of these by Dinali Fernando, now at Kelaniya, whose approach to students has always been both sympathetic and practical.

I hope then that, in addition to the texts from the book that I will discuss, students will read other texts in the book. In addition to poetry and fiction the book has texts on politics and history and law and international relations, about which one would hope postgraduate students would want some basic understanding.

Similarly, I do hope whoever teaches about Paradigms in English Education will prescribe a textbook so that students will understand more about what has been going on. Unfortunately, there has been little published about this but at least some students will I think benefit from my book on English and Education: In Search of Equity and Excellence? which Godage & Bros brought out in 2016. And then there was Lakmahal Justified: Taking English to the People, which came out in 2018, though that covers other topics too and only particular chapters will be relevant.

The former book is bulky but I believe it is entertaining as well. So, to conclude I will quote from it, to show what should not be done in Education and English. For instance, it is heartening that you are concerned with ‘social integration, co-existence and intercultural harmony’ and that you want to encourage ‘sensitivity towards different cultural and linguistic identities’. But for heaven’s sake do not do it as the NIE did several years ago in exaggerating differences. In those dark days, they produced textbooks which declared that ‘Muslims are better known as heavy eaters and have introduced many tasty dishes to the country. Watalappam and Buriani are some of these dishes. A distinguished feature of the Muslims is that they sit on the floor and eat food from a single plate to show their brotherhood. They eat string hoppers and hoppers for breakfast. They have rice and curry for lunch and dinner.’ The Sinhalese have ‘three hearty meals a day’ and ‘The ladies wear the saree with a difference and it is called the Kandyan saree’. Conversely, the Tamils ‘who live mainly in the northern and eastern provinces … speak the Tamil language with a heavy accent’ and ‘are a close-knit group with a heavy cultural background’’.

And for heaven’s sake do not train teachers by telling them that ‘Still the traditional ‘Transmission’ and the ‘Transaction’ roles are prevalent in the classroom. Due to the adverse standard of the school leavers, it has become necessary to develop the learning-teaching process. In the ‘Transmission’ role, the student is considered as someone who does not know anything and the teacher transmits knowledge to him or her. This inhibits the development of the student.

In the ‘Transaction’ role, the dialogue that the teacher starts with the students is the initial stage of this (whatever this might be). Thereafter, from the teacher to the class and from the class to the teacher, ideas flow and interaction between student-student too starts afterwards and turns into a dialogue. From known to unknown, simple to complex are initiated and for this to happen, the teacher starts questioning.’

And while avoiding such tedious jargon, please make sure their command of the language is better than to produce sentences such as these, or what was seen in an English text, again thankfully several years ago:

Read the story …

Hello! We are going to the zoo. “Do you like to join us” asked Sylvia. “Sorry, I can’t I’m going to the library now. Anyway, have a nice time” bye.

So Syliva went to the zoo with her parents. At the entrance her father bought tickets. First, they went to see the monkeys

She looked at a monkey. It made a funny face and started swinging Sylvia shouted: “He is swinging look now it is hanging from its tail its marvellous”

“Monkey usually do that’

I do hope your students will not hang from their tails as these monkeys do.

Midweek Review

Little known composers of classical super-hits

By Satyajith Andradi

Quite understandably, the world of classical music is dominated by the brand images of great composers. It is their compositions that we very often hear. Further, it is their life histories that we get to know. In fact, loads of information associated with great names starting with Beethoven, Bach and Mozart has become second nature to classical music aficionados. The classical music industry, comprising impresarios, music publishers, record companies, broadcasters, critics, and scholars, not to mention composers and performers, is largely responsible for this. However, it so happens that classical music lovers are from time to time pleasantly struck by the irresistible charm and beauty of classical pieces, the origins of which are little known, if not through and through obscure. Intriguingly, most of these musical gems happen to be classical super – hits. This article attempts to present some of these famous pieces and their little-known composers.

Pachelbel’s Canon in D

The highly popular piece known as Pachelbel’s Canon in D constitutes the first part of Johann Pachelbel’s ‘Canon and Gigue in D major for three violins and basso continuo’. The second part of the work, namely the gigue, is rarely performed. Pachelbel was a German organist and composer. He was born in Nuremburg in 1653, and was held in high esteem during his life time. He held many important musical posts including that of organist of the famed St Stephen’s Cathedral in Vienna. He was the teacher of Bach’s elder brother Johann Christoph. Bach held Pachelbel in high regard, and used his compositions as models during his formative years as a composer. Pachelbel died in Nuremburg in 1706.

Pachelbel’s Canon in D is an intricate piece of contrapuntal music. The melodic phrases played by one voice are strictly imitated by the other voices. Whilst the basso continuo constitutes a basso ostinato, the other three voices subject the original tune to tasteful variation. Although the canon was written for three violins and continuo, its immense popularity has resulted in the adoption of the piece to numerous other combinations of instruments. The music is intensely soothing and uplifting. Understandingly, it is widely played at joyous functions such as weddings.

Jeremiah Clarke’s Trumpet Voluntary

The hugely popular piece known as ‘Jeremiah Clarke’s Trumpet Voluntary’ appeared originally as ‘ The Prince of Denmark’s March’ in Jeremiah Clarke’s book ‘ Choice lessons for the Harpsichord and Spinet’, which was published in 1700 ( Michael Kennedy; Oxford Dictionary of Music ). Sometimes, it has also been erroneously attributed to England’s greatest composer Henry Purcell (1659 – 1695 ) and called ‘Purcell’s Trumpet Voluntary (Percy A. Scholes ; Oxford Companion to Music). This brilliant composition is often played at joyous occasions such as weddings and graduation ceremonies. Needless to say, it is a piece of processional music, par excellence. As its name suggests, it is probably best suited for solo trumpet and organ. However, it is often played for different combinations of instruments, with or without solo trumpet. It was composed by the English composer and organist Jeremiah Clarke.

Jeremiah Clarke was born in London in 1670. He was, like his elder contemporary Pachelbel, a musician of great repute during his time, and held important musical posts. He was the organist of London’s St. Paul’s Cathedral and the composer of the Theatre Royal. He died in London in 1707 due to self – inflicted gun – shot injuries, supposedly resulting from a failed love affair.

Albinoni’s Adagio

The full title of the hugely famous piece known as ‘Albinoni’s Adagio’ is ‘Adagio for organ and strings in G minor’. However, due to its enormous popularity, the piece has been arranged for numerous combinations of instruments. It is also rendered as an organ solo. The composition, which epitomizes pathos, is structured as a chaconne with a brooding bass, which reminds of the inevitability and ever presence of death. Nonetheless, there is no trace of despondency in this ethereal music. On the contrary, its intense euphony transcends the feeling of death and calms the soul. The composition has been attributed to the Italian composer Tomaso Albinoni (1671 – 1750), who was a contemporary of Bach and Handel. However, the authorship of the work is shrouded in mystery. Michael Kennedy notes: “The popular Adagio for organ and strings in G minor owes very little to Albinoni, having been constructed from a MS fragment by the twentieth century Italian musicologist Remo Giazotto, whose copyright it is” (Michael Kennedy; Oxford Dictionary of Music).

Boccherini’s Minuet

The classical super-hit known as ‘Boccherini’s Minuet’ is quite different from ‘Albinoni’s Adagio’. It is a short piece of absolutely delightful music. It was composed by the Italian cellist and composer Luigi Boccherini. It belongs to his string quintet in E major, Op. 13, No. 5. However, due to its immense popularity, the minuet is performed on different combinations of instruments.

Boccherini was born in Lucca in 1743. He was a contemporary of Haydn and Mozart, and an elder contemporary of Beethoven. He was a prolific composer. His music shows considerable affinity to that of Haydn. He lived in Madrid for a considerable part of his life, and was attached to the royal court of Spain as a chamber composer. Boccherini died in poverty in Madrid in 1805.

Like numerous other souls, I have found immense joy by listening to popular classical pieces like Pachelbel’s Canon in D, Jeremiah Clarke’s Trumpet Voluntary, Albinoni’s Adagio and Boccherini’s Minuet. They have often helped me to unwind and get over the stresses of daily life. Intriguingly, such music has also made me wonder how our world would have been if the likes of Bach, Handel, Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, and Schubert had never lived. Surely, the world would have been immeasurably poorer without them. However, in all probability, we would have still had Pachelbel’s Canon in D, Jeremiah Clarke’s Trumpet Voluntary, Albinoni’s Adagio, and Boccherini’s Minuet, to cheer us up and uplift our spirits.

Midweek Review

The Tax Payer and the Tough

By Lynn Ockersz

The tax owed by him to Caesar,

Leaves our retiree aghast…

How is he to foot this bill,

With the few rupees,

He has scraped together over the months,

In a shrinking savings account,

While the fires in his crumbling hearth,

Come to a sputtering halt?

But in the suave villa next door,

Stands a hulk in shiny black and white,

Over a Member of the August House,

Keeping an eagle eye,

Lest the Rep of great renown,

Be besieged by petitioners,

Crying out for respite,

From worries in a hand-to-mouth life,

But this thought our retiree horrifies:

Aren’t his hard-earned rupees,

Merely fattening Caesar and his cohorts?