Midweek Review

Colonial Knowledge Formation under British Rule and Modern Sri Lankan Historiography

The National Trust – Sri Lanka Monthly Lecture Series No- 129 October 29, 2020

By Prof. Gamini Keerawella

I am extremely thankful to Mr. Kanag-Isvaran, Chairman, the National Trust- Sri Lanka, for introducing me to this distinguished audience. I take this opportunity to thank the National Trust for the honour, bestowed upon me by inviting to deliverer this lecture. I really appreciate the kindness of Mr. Wickremerathne, Vice-Chair of the National Trust, who contacted me on behalf of the National Trust first, for giving me the liberty to decide the theme of the lecture. I decided to present my thoughts on ‘Colonial Knowledge Formation under British Rule and Modern Lankan Historiography’.

I am a historian by training. I am proud to be a historian. What we study in history is not really a dead past. Even though the events and personalities that we study are dead and gone, the thinking process behind these events and personalities are living and reemerging again and again in the minds of generation after generation. In that sense, all history is contemporary. The theme we discuss today is more relevant to the contemporary Sri Lankan political discourses. Tracing the genealogy of modern Sri Lankan historiography would help understand historical roots of the concepts on which the contemporary political discourse is centered.

In my lecture, I wish to elaborate three main points. First, the knowledge formation was a key component of the British colonialism project in Sri Lanka. The political and economic aspects of colonialism, the political domination and the extraction of resources have been given adequate attention. But, without paying attention to the Colonial knowledge formation, the totality of British colonial project cannot be grasped. Second, re-reading history in terms colonial political categories is a main component of colonial knowledge formation. The gathering information about the past of the colonial territories and their subjects was considered essential for building colonial hegemony and resource mobilization and exploitation in colonial territories. Third, the modern Sri Lankan Historiography took its form in the context of colonial knowledge formation under British rule. The main thrust of my argument is that modern Sri Lankan Historiography originated as a British colonial project.

Re-reading Sri Lankan History under British rule did not take place in an empty space. What really happened was that the text of pre-colonial Sri Lankan historiography was re-read in terms of the evolving new political categories. As a point of departure to my argument, I wish to draw your attention to attention to Historical traditions in Sri Lanka prior to colonialism.

Pre-colonial Sri Lankan Historiography

Sri Lanka had one of the oldest and continuous historical traditions in Asia. The origin of this historical tradition could be traced back to the introduction of Buddhism to the island in the 3rd century BC. When the Buddhist cannons were presented, they accompanied an historical introduction in the form of attakatha in order to prove that it was the true Buddha’s teaching. Acoordingly, attakatha to the Pitaka became an integral part of the introduction of Buddhism. This historical tradition was naturalized subsequently in Sri Lankan soil and the Sinhala attakatha were produced with added details of the history of the island. The Buddhist texts in Sinhala, including the commentaries, were once again translated into Pali in the 5th century A.D. The Samantapasadhika is a Pali translation of the Sinhala atuva of Vinaya Pitaka.

As a number of Buddhist centers of learning emerged in the island, there were many variations of historical narrations. The available evidence clearly shows that the ancient historical thinking of the island was enriched with multiple perspectives. In order to understand the ancient historical traditions of the island, Mahawamsa and its tika, Vamsatthappakasini are very useful. According to Mahavansa Tika, the Mahavamsa was based on the Sihalatthakatha Mahavamsa. The Vamsatthappakasini mentions about Uttaraviharatthakata and also Uttaravihara-vasinam Mahavamsa. Uttaravihara was Abhayagiriya, a rival Buddhist center that competed with Mahavihara. Uttaravihara historical perspective was not similar to Mahavihara. Almost all the quotations from the Uttaraviharatthakata in Mahawamsa are either to point out differences in the tradition or to provide additional information not found in Sihalatthakata. The author of Mahavamsa (first part) was Mahanama thera of Mahavihara and it presented the tradition nurtured in the Mahavihara.

The earliest known chronicle of the island was Dipavamsa, written around the mid 4th century A.D., little earlier than Mahavamsa. As Luxman Su Perera pointed out, Deepawamsa gives us a fair indication of the nature of the early historical tradition. ” The memory verses, the double versions and numerous repetitions show that it stands very close to the original. Consequently, it gives us a fair indication of the nature of the early historical tradition. The many references to bhikkunis have led scholars to suppose that this may be the work of the bhikkunis of the in the Hatthalhaka nunnery.

Even though there were multiple narratives, the unique place of the Mahavamsa and its overriding importance must not be underestimated. It continued to shape the dominant historical thinking of the island for generations. The Mahavamsa was in circulation as reference material for generations up to the 18th century. It is evident from a reference made by John Davy a medical officer of the British Army who served in Sri Lanka in the period 1816-1820, in his book, An Account of the Interior of Ceylon and of its Inhabitants.

‘Old Chroncile ‘

The historical sketch which forms the tenth chapter, and concludes the first part of the work, was drawn up chiefly from the information which I was so fortunate as to extract from the late Dissava of Welassey, Malawa, an old man of shrewd intellect, a poet, historian, and astrologer, and generally allowed by his countryman to be the most able and learned of all the Kandyan chiefs. Part of the information that he communicated was given from a very retentive memory, and part was drawn from an old chronicle, or other historical romance of Ceylon, which he had by him, and to which he referred when his memory failed him.

The ‘old chronicle’ that Davy referred to was no doubt Mahavamsa.

Pre-modern Sri Lanka historiography emerged and sustained in a particular socio-political and economic order. It was an organic part of reproduction of culture in that particular socio-political order. This order was replaced by a colonial order under the British rule. The colonial knowledge generation on acquired territories and subjugated people was a key component of colonial project.

Colonial knowledge formation

The practice of gathering information on the land, people, religions and languages of the East by colonial agents began from the very beginning of western colonial encounters in Asia. The Christian missionaries took the lead. They believed that familiarity of native languages, manners and customs would be essential in carrying out missionary work successfully.

Building knowledge of the colonial territories and their people in the East reached a new phase in the mid-19th century along with British colonial dominance in Asia. Its epicenter of British colonialism in Asia was India. Soon after the British acquired Bengal, Bihar and Orissa in the second half of the 18th century, the process of studying the people and their language and culture commenced systematically with the patronage of Warren Hastings, the first Governor General of British India. The connection between the colonial power projects and the renewed interest in the study of ancient languages, religions and history of the oriental people is abundantly clear. With the help of Brahmin Pandiths, Charles Wilkings translated Bhagavad Gîtâ into English in 1785. Writing a preface to the first English translation, Warren Hastings stated:

Every accumulation of knowledge and especially such as is obtained by social communication with the people over whom we exercise domination founded on the right of conquest, is useful to the state…it attracts and conciliates distant affections; it lessens the weight of the chain by which the natives are held in subjugation; and it imprints on the hearts of our countrymen the sense of obligation and benevolence…. Every instance which brings their real character home to observation will impress us with more generous sense of feeling for their natural rights, and teach us to estimate them by the measure of our own.

Charles Wilkins and Nathaniel Halhed, writers of the British East India Company in Bengal were among the first to study the Sanskrit. In 1783, William Jones came to India as a judge in the newly established Supreme Court of Bengal. As a judge in the Supreme Court, he was first interested in translating Manusmati (Laws of Manu) into English. He later translated Kalidasa’s Abhiknana Shakuntala and Ritu Samhara, and Jayadeva’s Gita Govinda into English. In the process of studying the society, he started learning Indian languages with the help of Brahmin Pundits of Bengal. William Jones was instrumental in establishing the Asiatick Society in 1784 in Bengal under the patronage of the Governor General Warren Hastings. In the third anniversary lecture of the Bengal Asiatic Society in 1786, William Jones stated:

The Sanskrit language, whatever be its antiquity, is of a wonderful structure; more perfect than the Greek, more copious than the Latin, and more exquisitely refined than either, yet bearing to both of them a stronger affinity, both in the roots of verbs and the forms of grammar, than could possibly have been produced by accident; so strong indeed, that no philologer could examine them all three, without believing them to have sprung from some common source, which, perhaps, no longer exists.

This statement not only challenged then prevailing Western perceptions of language history but also paved the way for the development of racial anthropology. William Jones statement of common source of origin of Sanskrit and the European clasical languages received a wide publicity. European philologers, historians, archeologists and ethnologists rushed to the East for intellectual pursuits in colonial environment.

In 1800, Governor Lord Wellesley established the Fort Williams College in Calcutta in order to train colonial civil servants. The Asiatic Society of Bengal and the Fort William College became one seat of Orientalist research where the concept of Indo-European family of languages originated. A while later, in 1812, Francis Whyte Ellis

cholarship of orientalisn , ann Histoty Colonial Collector of Madras presidency established the College of Fort St George to train young colonial civil servants of the Company in South India. The colonial administration in Madras, the Literary Society of Madras and the College of Fort St. George remained the triad of the Madras School of Orientalism. In 1816, F.W. Ellis first published proofs of the existence of the Dravidian language family, after studying ‘dhatu malas’ of the three South Indian languages- Telugu, Kannada and Tamil.

Comparative Grammar

In 1856, Bishop Robert Caldwell, elaborated it further and used the term ‘Dravidian’ to identify that language group in his Comparative Grammar of the Dravidian or South Indian Family of Languages. by quoting Pãnini and other ancient grammarians, Henry T. Colebrooke had argued in his article in Asian researches in 1801, titled ‘On the Sanskrit and Prakrit languages’, that Prakrit was the precursors of modern Indian languages, giving birth to the concept of linguistic unity of India. Now, the concept of linguistic unity of India was challenged by the Madras School of Orientalists, namely, Ellis, Campbell, and Caldwell.

Even though Britain took the lead in building new knowledge on the East but the other European colonial powers also claimed their shares. The first Oriental Society in Europe was the one founded by the Dutch in 1781 in order to map the languages in South East Asia. While Britain had its Royal Society (1823) the French had its own society- Acadèmie des Inscriptions et des Belles Letters. The competition between British and French orientalists to claim authority on oriental scholarship provided an impetus to ‘Oriental Studies’. Anquetil-Duperron, who worked for the French India Company in Pondicherry, returned to Paris with over two hundred manuscripts. His translation of Zend-Avesta and Ouvrage de Zoroastre was a reflection of French interest in Oriental Studies. William Jones who studied Persian at Oxford first came into prominence when he challenged the authority of Anquetil-Duperron.

The European contribution to the development of Oriental scholarship is important at this point. Paris became the main centre of the continental Europe for the construction of knowledge on the Orient. The first Chair of Sanskrit outside Britain was Antoine-Lẽonard de Chẽzy at the Collẽge de France. Eugẽne Bournouf later succeeded him. The first translation of Mahavamsa into an European language was done by Eugẽne Bournouf. In Paris, France Bopp and Max Mủller Studied Sanskrit under Bournouf. I will come to them later.

(To be continued)

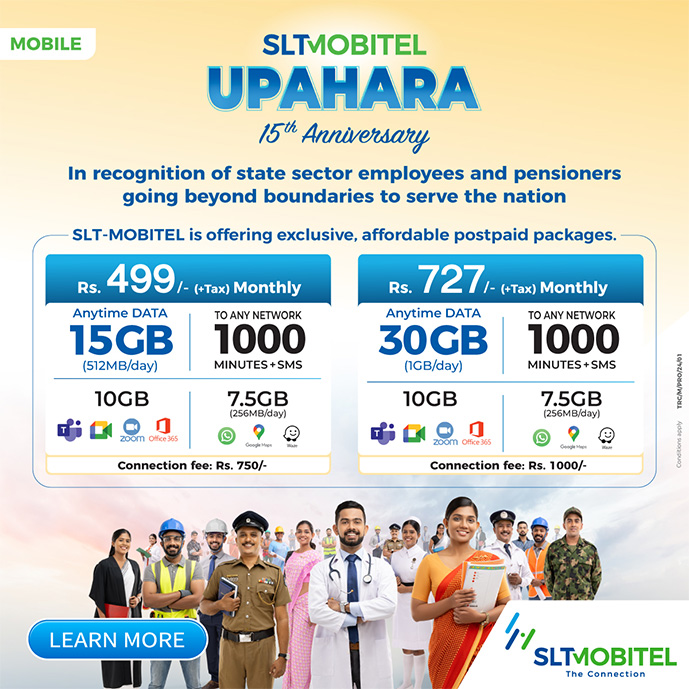

- News Advertiesment

See Kapruka’s top selling online shopping categories such as Toys, Grocery, Flowers, Birthday Cakes, Fruits, Chocolates, Clothing and Electronics. Also see Kapruka’s unique online services such as Money Remittence,News, Courier/Delivery, Food Delivery and over 700 top brands. Also get products from Amazon & Ebay via Kapruka Gloabal Shop into Sri Lanka.

Midweek Review

‘Professor of English Language Teaching’

It is a pleasure to be here today, when the University resumes postgraduate work in English and Education which we first embarked on over 20 years ago. The presence of a Professor on English Language Teaching from Kelaniya makes clear that the concept has now been mainstreamed, which is a cause for great satisfaction.

Twenty years ago, this was not the case. Our initiative was looked at askance, as indeed was the initiative which Prof. Arjuna Aluwihare engaged in as UGC Chairman to make degrees in English more widely available. Those were the days in which the three established Departments of English in the University system, at Peradeniya and Kelaniya and Colombo, were unbelievably conservative. Their contempt for his efforts made him turn to Sri Jayewardenepura, which did not even have a Department of English then and only offered it as one amongst three subjects for a General Degree.

Twenty years ago, this was not the case. Our initiative was looked at askance, as indeed was the initiative which Prof. Arjuna Aluwihare engaged in as UGC Chairman to make degrees in English more widely available. Those were the days in which the three established Departments of English in the University system, at Peradeniya and Kelaniya and Colombo, were unbelievably conservative. Their contempt for his efforts made him turn to Sri Jayewardenepura, which did not even have a Department of English then and only offered it as one amongst three subjects for a General Degree.

Ironically, the most dogmatic defence of this exclusivity came from Colombo, where the pioneer in English teaching had been Prof. Chitra Wickramasuriya, whose expertise was, in fact, in English teaching. But her successor, when I tried to suggest reforms, told me proudly that their graduates could go on to do postgraduate degrees at Cambridge. I suppose that, for generations brought up on idolization of E. F. C. Ludowyke, that was the acme of intellectual achievement.

I should note that the sort of idealization of Ludowyke, the then academic establishment engaged in was unfair to a very broadminded man. It was the Kelaniya establishment that claimed that he ‘maintained high standards, but was rarefied and Eurocentric and had an inhibiting effect on creative writing’. This was quite preposterous coming from someone who removed all Sri Lankan and other post-colonial writing from an Advanced Level English syllabus. That syllabus, I should mention, began with Jacobean poetry about the cherry-cheeked charms of Englishwomen. And such a characterization of Ludowyke totally ignored his roots in Sri Lanka, his work in drama which helped Sarachchandra so much, and his writing including ‘Those Long Afternoons’, which I am delighted that a former Sabaragamuwa student, C K Jayanetti, hopes to resurrect.

I have gone at some length into the situation in the nineties because I notice that your syllabus includes in the very first semester study of ‘Paradigms in Sri Lankan English Education’. This is an excellent idea, something which we did not have in our long-ago syllabus. But that was perhaps understandable since there was little to study then except a history of increasing exclusivity, and a betrayal of the excuse for getting the additional funding those English Departments received. They claimed to be developing teachers of English for the nation; complete nonsense, since those who were knowledgeable about cherries ripening in a face were not likely to move to rural areas in Sri Lanka to teach English. It was left to the products of Aluwihare’s initiative to undertake that task.

Another absurdity of that period, which seems so far away now, was resistance to training for teaching within the university system. When I restarted English medium education in the state system in Sri Lanka, in 2001, and realized what an uphill struggle it was to find competent teachers, I wrote to all the universities asking that they introduce modules in teacher training. I met condign refusal from all except, I should note with continuing gratitude, from the University of Sri Jayewardenepura, where Paru Nagasunderam introduced it for the external degree. When I started that degree, I had taken a leaf out of Kelaniya’s book and, in addition to English Literature and English Language, taught as two separate subjects given the language development needs of students, made the third subject Classics. But in time I realized that was not at all useful. Thankfully, that left a hole which ELT filled admirably at the turn of the century.

The title of your keynote speaker today, Professor of English Language Teaching, is clear evidence of how far we have come from those distant days, and how thankful we should be that a new generation of practical academics such as her and Dinali Fernando at Kelaniya, Chitra Jayatilleke and Madhubhashini Ratnayake at USJP and the lively lot at the Postgraduate Institute of English at the Open University are now making the running. I hope Sabaragamuwa under its current team will once again take its former place at the forefront of innovation.

To get back to your curriculum, I have been asked to teach for the paper on Advanced Reading and Writing in English. I worried about this at first since it is a very long time since I have taught, and I feel the old energy and enthusiasm are rapidly fading. But having seen the care with which the syllabus has been designed, I thought I should try to revive my flagging capabilities.

However, I have suggested that the university prescribe a textbook for this course since I think it is essential, if the rounded reading prescribed is to be done, that students should have ready access to a range of material. One of the reasons I began while at the British Council an intensive programme of publications was that students did not read round their texts. If a novel was prescribed, they read that novel and nothing more. If particular poems were prescribed, they read those poems and nothing more. This was especially damaging in the latter case since the more one read of any poet the more one understood what he was expressing.

Though given the short notice I could not prepare anything, I remembered a series of school textbooks I had been asked to prepare about 15 years ago by International Book House for what were termed international schools offering the local syllabus in the English medium. Obviously, the appalling textbooks produced by the Ministry of Education in those days for the rather primitive English syllabus were unsuitable for students with more advanced English. So, I put together more sophisticated readers which proved popular. I was heartened too by a very positive review of these by Dinali Fernando, now at Kelaniya, whose approach to students has always been both sympathetic and practical.

I hope then that, in addition to the texts from the book that I will discuss, students will read other texts in the book. In addition to poetry and fiction the book has texts on politics and history and law and international relations, about which one would hope postgraduate students would want some basic understanding.

Similarly, I do hope whoever teaches about Paradigms in English Education will prescribe a textbook so that students will understand more about what has been going on. Unfortunately, there has been little published about this but at least some students will I think benefit from my book on English and Education: In Search of Equity and Excellence? which Godage & Bros brought out in 2016. And then there was Lakmahal Justified: Taking English to the People, which came out in 2018, though that covers other topics too and only particular chapters will be relevant.

The former book is bulky but I believe it is entertaining as well. So, to conclude I will quote from it, to show what should not be done in Education and English. For instance, it is heartening that you are concerned with ‘social integration, co-existence and intercultural harmony’ and that you want to encourage ‘sensitivity towards different cultural and linguistic identities’. But for heaven’s sake do not do it as the NIE did several years ago in exaggerating differences. In those dark days, they produced textbooks which declared that ‘Muslims are better known as heavy eaters and have introduced many tasty dishes to the country. Watalappam and Buriani are some of these dishes. A distinguished feature of the Muslims is that they sit on the floor and eat food from a single plate to show their brotherhood. They eat string hoppers and hoppers for breakfast. They have rice and curry for lunch and dinner.’ The Sinhalese have ‘three hearty meals a day’ and ‘The ladies wear the saree with a difference and it is called the Kandyan saree’. Conversely, the Tamils ‘who live mainly in the northern and eastern provinces … speak the Tamil language with a heavy accent’ and ‘are a close-knit group with a heavy cultural background’’.

And for heaven’s sake do not train teachers by telling them that ‘Still the traditional ‘Transmission’ and the ‘Transaction’ roles are prevalent in the classroom. Due to the adverse standard of the school leavers, it has become necessary to develop the learning-teaching process. In the ‘Transmission’ role, the student is considered as someone who does not know anything and the teacher transmits knowledge to him or her. This inhibits the development of the student.

In the ‘Transaction’ role, the dialogue that the teacher starts with the students is the initial stage of this (whatever this might be). Thereafter, from the teacher to the class and from the class to the teacher, ideas flow and interaction between student-student too starts afterwards and turns into a dialogue. From known to unknown, simple to complex are initiated and for this to happen, the teacher starts questioning.’

And while avoiding such tedious jargon, please make sure their command of the language is better than to produce sentences such as these, or what was seen in an English text, again thankfully several years ago:

Read the story …

Hello! We are going to the zoo. “Do you like to join us” asked Sylvia. “Sorry, I can’t I’m going to the library now. Anyway, have a nice time” bye.

So Syliva went to the zoo with her parents. At the entrance her father bought tickets. First, they went to see the monkeys

She looked at a monkey. It made a funny face and started swinging Sylvia shouted: “He is swinging look now it is hanging from its tail its marvellous”

“Monkey usually do that’

I do hope your students will not hang from their tails as these monkeys do.

Midweek Review

Little known composers of classical super-hits

By Satyajith Andradi

Quite understandably, the world of classical music is dominated by the brand images of great composers. It is their compositions that we very often hear. Further, it is their life histories that we get to know. In fact, loads of information associated with great names starting with Beethoven, Bach and Mozart has become second nature to classical music aficionados. The classical music industry, comprising impresarios, music publishers, record companies, broadcasters, critics, and scholars, not to mention composers and performers, is largely responsible for this. However, it so happens that classical music lovers are from time to time pleasantly struck by the irresistible charm and beauty of classical pieces, the origins of which are little known, if not through and through obscure. Intriguingly, most of these musical gems happen to be classical super – hits. This article attempts to present some of these famous pieces and their little-known composers.

Pachelbel’s Canon in D

The highly popular piece known as Pachelbel’s Canon in D constitutes the first part of Johann Pachelbel’s ‘Canon and Gigue in D major for three violins and basso continuo’. The second part of the work, namely the gigue, is rarely performed. Pachelbel was a German organist and composer. He was born in Nuremburg in 1653, and was held in high esteem during his life time. He held many important musical posts including that of organist of the famed St Stephen’s Cathedral in Vienna. He was the teacher of Bach’s elder brother Johann Christoph. Bach held Pachelbel in high regard, and used his compositions as models during his formative years as a composer. Pachelbel died in Nuremburg in 1706.

Pachelbel’s Canon in D is an intricate piece of contrapuntal music. The melodic phrases played by one voice are strictly imitated by the other voices. Whilst the basso continuo constitutes a basso ostinato, the other three voices subject the original tune to tasteful variation. Although the canon was written for three violins and continuo, its immense popularity has resulted in the adoption of the piece to numerous other combinations of instruments. The music is intensely soothing and uplifting. Understandingly, it is widely played at joyous functions such as weddings.

Jeremiah Clarke’s Trumpet Voluntary

The hugely popular piece known as ‘Jeremiah Clarke’s Trumpet Voluntary’ appeared originally as ‘ The Prince of Denmark’s March’ in Jeremiah Clarke’s book ‘ Choice lessons for the Harpsichord and Spinet’, which was published in 1700 ( Michael Kennedy; Oxford Dictionary of Music ). Sometimes, it has also been erroneously attributed to England’s greatest composer Henry Purcell (1659 – 1695 ) and called ‘Purcell’s Trumpet Voluntary (Percy A. Scholes ; Oxford Companion to Music). This brilliant composition is often played at joyous occasions such as weddings and graduation ceremonies. Needless to say, it is a piece of processional music, par excellence. As its name suggests, it is probably best suited for solo trumpet and organ. However, it is often played for different combinations of instruments, with or without solo trumpet. It was composed by the English composer and organist Jeremiah Clarke.

Jeremiah Clarke was born in London in 1670. He was, like his elder contemporary Pachelbel, a musician of great repute during his time, and held important musical posts. He was the organist of London’s St. Paul’s Cathedral and the composer of the Theatre Royal. He died in London in 1707 due to self – inflicted gun – shot injuries, supposedly resulting from a failed love affair.

Albinoni’s Adagio

The full title of the hugely famous piece known as ‘Albinoni’s Adagio’ is ‘Adagio for organ and strings in G minor’. However, due to its enormous popularity, the piece has been arranged for numerous combinations of instruments. It is also rendered as an organ solo. The composition, which epitomizes pathos, is structured as a chaconne with a brooding bass, which reminds of the inevitability and ever presence of death. Nonetheless, there is no trace of despondency in this ethereal music. On the contrary, its intense euphony transcends the feeling of death and calms the soul. The composition has been attributed to the Italian composer Tomaso Albinoni (1671 – 1750), who was a contemporary of Bach and Handel. However, the authorship of the work is shrouded in mystery. Michael Kennedy notes: “The popular Adagio for organ and strings in G minor owes very little to Albinoni, having been constructed from a MS fragment by the twentieth century Italian musicologist Remo Giazotto, whose copyright it is” (Michael Kennedy; Oxford Dictionary of Music).

Boccherini’s Minuet

The classical super-hit known as ‘Boccherini’s Minuet’ is quite different from ‘Albinoni’s Adagio’. It is a short piece of absolutely delightful music. It was composed by the Italian cellist and composer Luigi Boccherini. It belongs to his string quintet in E major, Op. 13, No. 5. However, due to its immense popularity, the minuet is performed on different combinations of instruments.

Boccherini was born in Lucca in 1743. He was a contemporary of Haydn and Mozart, and an elder contemporary of Beethoven. He was a prolific composer. His music shows considerable affinity to that of Haydn. He lived in Madrid for a considerable part of his life, and was attached to the royal court of Spain as a chamber composer. Boccherini died in poverty in Madrid in 1805.

Like numerous other souls, I have found immense joy by listening to popular classical pieces like Pachelbel’s Canon in D, Jeremiah Clarke’s Trumpet Voluntary, Albinoni’s Adagio and Boccherini’s Minuet. They have often helped me to unwind and get over the stresses of daily life. Intriguingly, such music has also made me wonder how our world would have been if the likes of Bach, Handel, Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, and Schubert had never lived. Surely, the world would have been immeasurably poorer without them. However, in all probability, we would have still had Pachelbel’s Canon in D, Jeremiah Clarke’s Trumpet Voluntary, Albinoni’s Adagio, and Boccherini’s Minuet, to cheer us up and uplift our spirits.

Midweek Review

The Tax Payer and the Tough

By Lynn Ockersz

The tax owed by him to Caesar,

Leaves our retiree aghast…

How is he to foot this bill,

With the few rupees,

He has scraped together over the months,

In a shrinking savings account,

While the fires in his crumbling hearth,

Come to a sputtering halt?

But in the suave villa next door,

Stands a hulk in shiny black and white,

Over a Member of the August House,

Keeping an eagle eye,

Lest the Rep of great renown,

Be besieged by petitioners,

Crying out for respite,

From worries in a hand-to-mouth life,

But this thought our retiree horrifies:

Aren’t his hard-earned rupees,

Merely fattening Caesar and his cohorts?