Features

Implementing the Paddy Lands Act of 1958 – the Cultivation Committees

by Chandra Arulpragasam

Introduction: A Personal Note

In the CCS in early 1958, I was appointed Deputy Commissioner of the Agrarian Services Department, in charge of implementing the Paddy Lands Act of 1958. In setting out to draft the Administrative Regulations under the Act, I came across a number of structural, legal and operational considerations, which probably had not been foreseen by its authors. This was probably the first time that it was being looked at by an administrator with field experience – and the first time that it was being looked at by someone who was new to the Paddy Lands Act and to its thinking.

First, from a conceptual side, the concept and design of the Act did not fit, for example, the agrarian conditions of the Batticaloa district, which raised some problems of implementation. Secondly, because of the Act’s contentious nature, its legal provisions were likely to be challenged and its implementation obstructed. This made it necessary to examine its provisions from an adversarial point of view – which revealed many legal and administrative vulnerabilities. Thirdly, there were new problems of implementation. For example, the Act safeguarded tenants, but there were no records of tenants or of landlords. New records of land ownership, tenancy, etc. would have to be created from scratch before implementation could even begin.

In comparison, the land records in India, Pakistan and Bangladesh had been built up over a period of 200 years by the British imperial power. How could such records be created within six months before the Act would become operational in six districts of the country – as stipulated in the Act? Moreover, there were all sorts of potential legal and administrative problems in the elections of the Cultivation Committees. And so on.

The Commissioner of Agrarian Services happened to be abroad for three weeks. Thus, not only was I was the Acting Head of a Class I, Grade 1 Department at the age of 28 years, but I also needed policy-level help, because this was hitherto unchartered territory in the country. So I asked for an appointment with the Minister of Agriculture, Mr. Phillip Gunawardene, the author of the Act, whom I had never met or seen before. The Minister was charming, affable and even fatherly, over a cup of tea and cakes in Parliament. Getting down to business, I brought to his notice the number of legal difficulties and some of the administrative problems that needed his guidance.

I was so intent on my presentation of the potential legal problems of the Cultivation Committees that I failed to notice that he had tossed his spectacles on the table, which was a sign (I was told later) that he was losing his patience – and his temper. I was only half way through my list when he suddenly banged his fist on the table with a loud noise, stopping me abruptly. “Young man” he exclaimed: “Have you come across these difficulties in the field – or are they in your head?” When I pointed weakly to my head, “Go and work”, he thundered! “And when you come across these problems, then you come to me!” In complete disarray, I scooped up my files and scooted from Parliament, leaving a trail of paper in my wake! This was the first and last time that I saw Mr. Phillip Gunawardene.

Within a few months, he was isolated and pushed out of the Cabinet, to be succeeded as Minister of Agriculture by Mr. C. P. de Silva. This resulted in two difficulties that I had to face. Within a few months, every one of the legal and administrative problems that I had raised with the Minister had actually come to pass. But secondly, when I needed ministerial help, Mr. Phillip Gunawardene, was no longer there. Instead, there was a new Minister, Mr. C.P de Silva, his political foe, who was actually opposed to the Act, and who decided to let it fester in its own legal difficulties so as to discredit it countrywide. In fact, I had to battle with the new Minister to amend the Act in order to give effect to the intentions of Parliament, or to repeal it. I gathered that he was not prepared to go to Parliament to publicly repeal it, since it was publicly popular. As late as 1960, I was struggling to get the same loopholes plugged that I had pointed out to the former Minister (Mr. Philip Gunawardene) in 1958.

Although upset by my encounter with Mr.Phillip Gunawardene, I came later to recognize that I had been looking at it only from my own administive and legal point of view, not appreciating his political difficulties in going back to Parliament for amendments before implementation had even began! Although I never met Mr. Gunawardene thereafter, he must have appreciated my work, for he later paid me a handsome compliment in Parliament, as recorded in Hansard.

New Ideas: The Role of the Cultivation Committees

Starting from the premise that the state machinery, especially at lower levels, was subject to the influence of the landlords, the Paddy Lands Act created a new Agrarian Services Department at national level, devoted to its implementation. Moreover, in order to bypass the lower level of administration at field level (which was thought to be under landlord influence), it created Cultivation Committees with assured majorities for the actual cultivators. This attempt to bias the administration in favour of the weaker sections of the agrarian society represented a change from the view prevailing from colonial times, namely, that the administration would be neutral in its dealings with all sections of the public. It is relevant to note here that most of the agrarian reform programmes in Latin America started from the same premise. Similarly, they opted for separate, dedicated agencies for the implementation of their land reforms, outside their existing ministries. The experiences of Japan, South Korea and Taiwan were quite different because their land reforms were carried out under martial law, or with the active backing of the military.

The Act was also innovatory in that it represented the first time in any country in South and South East Asia that legal powers in the implementation of tenurial reforms and the management of irrigation and cultivation at field levels were given to an elected body. The idea that an elected body of semi-educated farmers could take over functions from the government bureaucracy was clearly revolutionary at that time. For example, since the rent payable on a particular field was fixed as one-fourth share of the harvest, how could a distant court know how much the gross harvest of a particular field was? The Act recognized that such factual questions at field level could only be answered at field level. The failure to recognize this and to provide for beneficiary participation in implementing such reforms has been one of the greatest weaknesses of similar programmes in other countries of the region at that time.

The first role of the Cultivation Committees was to help in the implementation of the tenancy provisions of the Act (Sections 8-19). The Committees were also authorized to act as intermediaries between landlord and tenant in the collection of rents, etc., thus reducing the personal hold of landlords over their tenants. The Cultivation Committees were thus expected to play an important socio-psychological role in bolstering the confidence of the tenant-cultivators to actively claim their rights under the law.

Secondly, the Cultivation Committees were given important development functions, with powers for the advancement of paddy cultivation in their areas. They were given access to technical advice in the form of Agricultural Extension Officers and Village Cultivation Officers, who were made ex-officio members of the Committees; but with a right only to speak but not to vote at their meetings. It was hoped that with such technical advice emanating from within, and adopted by the Committees, would enable both paddy production and water-management to be greatly improved by the farmers, acting on their own volition..

A third major innovatory function of the Cultivation Committees was in respect of (irrigation) water management, with the Committees taking over the functions of the Irrigation Headmen (Vel Vidanes) at field level. These functions, among others, included enforcement of rules relating to cultivation dates, clearing of channels, fencing, etc, as well as improving water management. This was in a context where bureaucratic and technical means of water management at field level had already failed. The Paddy Lands Act of 1958 thus predated international recognition of the need for farmer participation in water-management by at least 20 years! In practice, however, the Cultivation Committees under the Act of 1958 never made any progress in this field because they were legally invalidated soon after their formation.

A fourth innovation was in the field of agricultural extension. It was evident then, and more evident now, that agricultural extension systems based on the western models of one extension worker dealing face-to-face with each individual farmer were completely unrealistic in most developing countries with a multitude of small farmers. For example, in Nepal, an extension agent would have to walk one whole day to even reach 50 farmers in remote vellages! No developing country in the world could afford such a system in the context of multiple small farmers, which would require a quadrupling or more of extension workers. Ironically, this has been the recommendation of FAO and the World Bank for decades since the Paddy Lands Act of 1958! It is therefore obvious that a two-stage system or a group system of extension had to be devised, either with the extension agent working through farmer leaders, or through a system of group-extension, as envisaged by the Paddy Lands Act. Thus, the Act’s introduction of such a group extension system with farmer education and participation in the planning and implementation of such self-decided programmes of agricultural development was at least 40 years ahead of its time.

Lastly, the tenurial provisions of the Paddy Lands Act needed to be supported by a broader package of institutional support for smallholder agriculture, in order for the Act itself to be effective. Such a package was provided by the establishment of the multipurpose cooperatives, agricultural credit for smallholders, a fertilizer subsidy, a guaranteed price for paddy and a pilot crop insurance scheme. It is important to recognize that the Green Revolution could not have taken off in Sri Lanka around 1967 if the institutional support structure for small-scale paddy farming had not been laid in the late 1950s, alongside and with the Paddy Lands Act.

While the Act provided for an active role by farmers’ organizations (the Cultivation Committees), it is clear that the latter were not neutral farmer organizations. It was known, for example, that the village cooperatives in most countries of South Asia were under the control of the big landlords. The Paddy Lands Act, therefore, went to great lengths to neutralize the overweening power of the landlords by weighting these Committees heavily in favour of the actual cultivators. The landlords, however, retaliated by getting the Cultivation Committees declared legally invalid. This had the effect of cutting off the implementation structure at the knees, with no feet on the ground, making field level implementation impossible.

Thus one of the main laudatory features of the Act, namely, its provision for beneficiary participation, proved also to be its Achilles heel, leading ultimately to its collapse. Although such local farmers’ associations weighted in favour of the actual tillers succeeded in Japan, Taiwan and South Korea, they were supported by martial law, or by military force. In contrast, our Cultivation Committees were subject to a judicial system under the rule of law in a democracy. In fact, it even allowed a President of a Village Tribunal to famously declare from the bench: “Pillippua Parippua-ge kumburu panatha appete epa” (We do not want lousy Phillip’s Paddy Lands Act!)

The Department of Agrarian Services organized rounds of field-level meetings, trying to encourage the Cultivation Committees to hold fast, promising that legal amendments would soon be forthcoming to remedy their legal incapacity. But in fact, these amendments came too late. They were passed only after the landlords had already evicted their tenants, and only after the Cultivation Committees had been seen to have failed in their cultivation and irrigation duties, thus losing the confidence of the farmers themselves.

It is also necessary to consider the socio-political climate in the villages at that time. There was euphoria among the tenant-cultivators and agricultural workers when the Act was passed, heightened by their participation in the formation of the Cultivation Committees, which they felt would support them against arbitrary eviction and higher rents.

This enthusiasm was reflected in other aspects of cultivation too. Fertilizer consumption doubled in the first year of the formation of the Cultivation Committees, but collapsed in the year following their legal invalidation. This collapse caused great demoralization among the cultivators, since they had gained great socio-psychological support from the Committees in standing up for their rights. With their collapse, many tenants surrendered their rights, accepting their plight as “hidden tenants” with no rights under the law. There was chaos in the paddy fields too, since there was no agent/agency left to ensure that the fields were fenced or the water issued. Hence, by the time the Cultivation Committees were re-legalized by the Paddy Lands (Amendment) Acts of 1961 and 1964, the latter served only to close the stable door after the horse had bolted. The Committees never regained the vigour and vibrancy that accompanied the first flush of their formation under the Act of 1958.

Legal and Administrative Challenges: The Collapse of the Cultivation Committees

It is left only to record the legal arguments that led to the collapse of the Cultivation Committees of 1958 – which provides a lesson in itself of how legal finagling can upset progressive legislation. A Cultivation Committee was to consist of twelve (12) members (Section 29). “Of the prescribed number of elected members of the Committee: (a) not less than three-fourths shall be elected by the qualified cultivators……; and (b) not more than one-fourth shall be elected by the qualified owners….” Clearly the intention was to give greater weight in the Committees to the actual cultivators as opposed to the landlords.

In administrative terms, it was clear that there had to be two separate elections: one for the owners to elect their members, and one for the actual cultivators to elect theirs. This required that separate electoral lists be prepared for the owners and separate ones for the cultivators. Given the predictable opposition from the landlords, every name on every electoral list was liable to be challenged, while the elections themselves could be disputed in law. I had pointed this out to Mr. Phillip Gunawardene in my first and only encounter with him.

But there were even more serious problems. Since the law and relevant regulations stipulated that all Cultivation Committees shall have twelve members, the refusal by landlords to elect their representatives would render most of the Committees invalid. This again was a potential problem that I had brought to the notice of the Minister in my initial and only meeting with him – for which I was chased out by him! Faced with this situation on the ground one year later, we took the position (with the agreement of the Attorney-General) that if the landlords failed to elect their three representatives, the cultivators could elect the full twelve members of the Committee, since they (the cultivators) were entitled to elect a number “not less than three-fourths” of the Committee. The landlords then consulted Mr. H. V. Pereira, the highest legal luminary in the country. His brilliant mathematical argument in the appellate court was that since the landlords were to elect “a number “… “not more than one-fourth”, and since the qualified owners had elected nought representatives, and since nought is not a number, the Cultivation Committees were not legally constituted! On this abtruse mathematical argument, the Court decided that the Cultivation Committees were not legally constituted!

All past and future actions of such Committees were also declared null and void! This ruling encouraged the landlords to boycott the Cultivation Committee elections all over the country, thus rendering them legally invalid and their actions legally void. Thus the implementation machinery of the Act at field level was completely demolished on the basis of this legal argument! Since these Committees had by law taken over important irrigation and cultivation functions (the vel vidanes having been abolished) their invalidation led to a breakdown in the common arrangements for cultivation and irrigation, thus causing complete chaos in the field. And the Minister in charge of its implementation (Mr.C.P. de Silva) was not prepared to pass the needed amendments to plug the legal loopholes.

This placed me, as the implementer, in a professionally unenviable position. On the one hand, my duty was to implement the Act; but on the other, my own Minister who was also supposed to be implementing the Act, seemed intent on making its implementation impossible. Nor was he willing to repeal the Act, since it still had popular appeal. Two Commissioners of the Agrarian Services had been transferred out of the Department because they had agreed to sign the needed amendments to plug the loopholes in the Act. After more than two years of this unequal and unsuccessful struggle, I capitulated and sought a transfer out of the Ministry.

(The writer, a former member of the Ceylon Civil Service, later worked for a long period at the UN’s FAO in Rome).

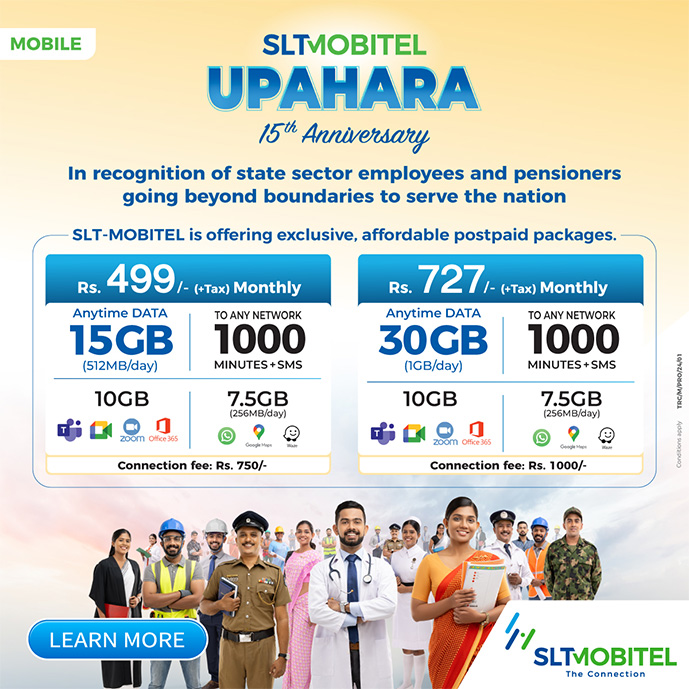

- News Advertiesment

See Kapruka’s top selling online shopping categories such as Toys, Grocery, Flowers, Birthday Cakes, Fruits, Chocolates, Clothing and Electronics. Also see Kapruka’s unique online services such as Money Remittence,News, Courier/Delivery, Food Delivery and over 700 top brands. Also get products from Amazon & Ebay via Kapruka Gloabal Shop into Sri Lanka.

Features

Islamophobia and the threat to democratic development

There’s an ill more dangerous and pervasive than the Coronavirus that’s currently sweeping Sri Lanka. That is the fear to express one’s convictions. Across the public sector of the country in particular many persons holding high office are stringently regulating and controlling the voices of their consciences and this bodes ill for all and the country.

The corrupting impact of fear was discussed in this column a couple of weeks ago when dealing with the military coup in Myanmar. It stands to the enduring credit of ousted Myanmarese Head of Government Aung San Suu Kyi that she, perhaps for the first time in the history of modern political thought, singled out fear, and not power, as the principal cause of corruption within the individual; powerful or otherwise.

To be sure, power corrupts but the corrupting impact of fear is graver and more devastating. For instance, the fear in a person holding ministerial office or in a senior public sector official, that he would lose position and power as a result of speaking out his convictions and sincere beliefs on matters of the first importance, would lead to a country’s ills going unaddressed and uncorrected.

Besides, the individual concerned would be devaluing himself in the eyes of all irrevocably and revealing himself to be a person who would be willing to compromise his moral integrity for petty worldly gain or a ‘mess of pottage’. This happens all the while in Lankan public life. Some of those who have wielded and are wielding immense power in Sri Lanka leave very much to be desired from these standards.

It could be said that fear has prevented Sri Lanka from growing in every vital respect over the decades and has earned for itself the notoriety of being a directionless country.

All these ills and more are contained in the current controversy in Sri Lanka over the disposal of the bodies of Covid victims, for example. The Sri Lankan polity has no choice but to abide by scientific advice on this question. Since authorities of the standing of even the WHO have declared that the burial of the bodies of those dying of Covid could not prove to be injurious to the wider public, the Sri Lankan health authorities could go ahead and sanction the burying of the bodies concerned. What’s preventing the local authorities from taking this course since they claim to be on the side of science? Who or what are they fearing? This is the issue that’s crying out to be probed and answered.

All these ills and more are contained in the current controversy in Sri Lanka over the disposal of the bodies of Covid victims, for example. The Sri Lankan polity has no choice but to abide by scientific advice on this question. Since authorities of the standing of even the WHO have declared that the burial of the bodies of those dying of Covid could not prove to be injurious to the wider public, the Sri Lankan health authorities could go ahead and sanction the burying of the bodies concerned. What’s preventing the local authorities from taking this course since they claim to be on the side of science? Who or what are they fearing? This is the issue that’s crying out to be probed and answered.

Considering the need for absolute truthfulness and honesty on the part of all relevant persons and quarters in matters such as these, the latter have no choice but to resign from their positions if they are prevented from following the dictates of their consciences. If they are firmly convinced that burials could bring no harm, they are obliged to take up the position that burials should be allowed.

If any ‘higher authority’ is preventing them from allowing burials, our ministers and officials are conscience-bound to renounce their positions in protest, rather than behave compromisingly and engage in ‘double think’ and ‘double talk’. By adopting the latter course they are helping none but keeping the country in a state of chronic uncertainty, which is a handy recipe for social instabiliy and division.

In the Sri Lankan context, the failure on the part of the quarters that matter to follow scientific advice on the burials question could result in the aggravation of Islamophobia, or hatred of the practitioners of Islam, in the country. Sri Lanka could do without this latter phobia and hatred on account of its implications for national stability and development. The 30 year war against separatist forces was all about the prevention by military means of ‘nation-breaking’. The disastrous results for Sri Lanka from this war are continuing to weigh it down and are part of the international offensive against Sri Lanka in the UNHCR.

However, Islamophobia is an almost world wide phenomenon. It was greatly strengthened during Donald Trump’s presidential tenure in the US. While in office Trump resorted to the divisive ruling strategy of quite a few populist authoritarian rulers of the South. Essentially, the manoeuvre is to divide and rule by pandering to the racial prejudices of majority communities.

It has happened continually in Sri Lanka. In the initial post-independence years and for several decades after, it was a case of some populist politicians of the South whipping-up anti-Tamil sentiments. Some Tamil politicians did likewise in respect of the majority community. No doubt, both such quarters have done Sri Lanka immeasurable harm. By failing to follow scientific advice on the burial question and by not doing what is right, Sri Lanka’s current authorities are opening themselves to the charge that they are pandering to religious extremists among the majority community.

The murderous, destructive course of action adopted by some extremist sections among Muslim communities world wide, including of course Sri Lanka, has not earned the condemnation it deserves from moderate Muslims who make-up the preponderant majority in the Muslim community. It is up to moderate opinion in the latter collectivity to come out more strongly and persuasively against religious extremists in their midst. It will prove to have a cementing and unifying impact among communities.

It is not sufficiently appreciated by governments in the global South in particular that by voicing for religious and racial unity and by working consistently towards it, they would be strengthening democratic development, which is an essential condition for a country’s growth in all senses.

A ‘divided house’ is doomed to fall; this is the lesson of history. ‘National security’ cannot be had without human security and peaceful living among communities is central to the latter. There cannot be any ‘double talk’ or ‘politically correct’ opinions on this question. Truth and falsehood are the only valid categories of thought and speech.

Those in authority everywhere claiming to be democratic need to adopt a scientific outlook on this issue as well. Studies conducted on plural societies in South Asia, for example, reveal that the promotion of friendly, cordial ties among communities invariably brings about healing among estranged groups and produces social peace. This is the truth that is waiting to be acted upon.

Features

Pakistan’s love of Sri Lanka

By Sanjeewa Jayaweera

It was on 3rd January 1972 that our family arrived in Karachi from Moscow. Our departure from Moscow had been delayed for a few weeks due to the military confrontation between Pakistan and India. It ended on 16th December 1971. After that, international flights were not permitted for some time.

The contrast between Moscow and Karachi was unbelievable. First and foremost, Moscow’s temperature was near minus 40 degrees centigrade, while in Karachi, it was sunny and a warm 28 degrees centigrade. However, what struck us most was the extreme warmth with which the airport authorities greeted our family. As my father was a diplomat, we were quickly ushered to the airport’s VIP Lounge. We were in transit on our way to Rawalpindi, the airport serving the capital of Islamabad.

We quickly realized that the word “we are from Sri Lanka” opened all doors just as saying “open sesame” gained entry to Aladdin’s cave! The broad smile, extreme courtesy, and genuine warmth we received from the Pakistani people were unbelievable.

This was all to do with Mrs Sirima Bandaranaike’s decision to allow Pakistani aircraft to land in Colombo to refuel on the way to Dhaka in East Pakistan during the military confrontation between Pakistan and India. It was a brave decision by Mrs Bandaranaike (Mrs B), and the successive governments and Sri Lanka people are still enjoying the fruits of it. Pakistan has been a steadfast and loyal supporter of our country. They have come to our assistance time and again in times of great need when many have turned their back on us. They have indeed been an “all-weather” friend of our country.

Getting back to 1972, I was an early beneficiary of Pakistani people’s love for Sri Lankans. I failed the entrance exam to gain entry to the only English medium school in Islamabad! However, when I met the Principal, along with my father, he said, “Sanjeewa, although you failed the entrance exam, I will this time make an exception as Sri Lankans are our dear friends.” After that, the joke around the family dinner table was that I owed my education in Pakistan to Mrs B!

At school, my brother and I were extended a warm welcome and always greeted “our good friends from Sri Lanka.” I felt when playing cricket for our college; our runs were cheered more loudly than of others.

One particular incident that I remember well was when the Embassy received a telex from the Foreign inistry. It requested that our High Commissioner seek an immediate meeting with the Prime Minister of Pakistan, Mr Zulifikar Ali Bhutto (ZB), and convey a message from Mrs B. The message requested that an urgent shipment of rice be dispatched to Sri Lanka as there would be an imminent rice shortage. As the Ambassador was not in the station, the responsibility devolved on my father.

It usually takes about a week or more to get an audience with the Prime Minister (PM) of a foreign country due to their busy schedule. However, given the urgency, my father spoke to the Foreign Ministry’s Permanent Sectary, who fortunately was our neighbour and sought an urgent appointment. My father received a call from the PM’s secretary around 10 P.M asking him to come over to the PM’s residence. My father met ZB around midnight. ZB was about to retire to bed and, as such, was in his pyjamas and gown enjoying a cigar! He had greeted my father and had asked, “Mr Jayaweera, what can we do for great friend Madam Bandaranaike?. My father conveyed the message from Colombo and quietly mentioned that there would be riots in the country if there is no rice!

ZB had immediately got the Food Commissioner of Pakistan on the line and said, “I want a shipload of rice to be in Colombo within the next 72 hours!” The Food Commissioner reverted within a few minutes, saying that nothing was available and the last export shipment had left the port only a few hours ago to another country. ZB had instructed to turn the ship around and send it to Colombo. This despite protests from the Food Commissioner about terms and conditions of the Letter of Credit prohibiting non-delivery. Sri Lanka got its delivery of rice!

The next was the visit of Mrs B to Pakistan. On arrival in Rawalpindi airport, she was given a hero’s welcome, which Pakistan had previously only offered to President Gaddafi of Libya, who financially backed Pakistan with his oil money. That day, I missed school and accompanied my parents to the airport. On our way, we witnessed thousands of people had gathered by the roadside to welcome Mrs B.

When we walked to the airport’s tarmac, thousands of people were standing in temporary stands waving Sri Lanka and Pakistan flags and chanting “Sri Lanka Pakistan Zindabad.” The noise emanating from the crowd was as loud and passionate as the cheering that the Pakistani cricket team received during a test match. It was electric!

I believe she was only the second head of state given the privilege of addressing both assemblies of Parliament. The other being Gaddafi. There was genuine affection from Mrs B amongst the people of Pakistan.

I always remember the indefatigable efforts of Mr Abdul Haffez Kardar, a cabinet minister and the President of the Pakistan Cricket Board. From around 1973 onwards, he passionately championed Sri Lanka’s cause to be admitted as a full member of the International Cricket Council (ICC) and granted test status. Every year, he would propose at the ICC’s annual meeting, but England and Australia’s veto kept us out until 1981.

I always felt that our Cricket Board made a mistake by not inviting Pakistan to play our inaugural test match. We should have appreciated Mr Kardar and Pakistan’s efforts. In 1974 the Pakistan board invited our team for a tour involving three test matches and a few first-class games. Most of those who played in our first test match was part of that tour, and no doubt gained significant exposure playing against a highly talented Pakistani team.

Several Pakistani greats were part of the Pakistan and India team that played a match soon after the Central Bank bomb in Colombo to prove that it was safe to play cricket in Colombo. It was a magnificent gesture by both Pakistan and India. Our greatest cricket triumph was in Pakistan when we won the World Cup in 1996. I am sure the players and those who watched the match on TV will remember the passionate support our team received that night from the Pakistani crowd. It was like playing at home!

I also recall reading about how the Pakistani government air freighted several Multi Barrell artillery guns and ammunition to Sri Lanka when the A rmy camp in Jaffna was under severe threat from the LTTE. This was even more important than the shipload of rice that ZB sent. This was crucial as most other countries refused to sell arms to our country during the war.

Time and again, Pakistan has steadfastly supported our country’s cause at the UNHCR. No doubt this year, too, their diplomats will work tirelessly to assist our country.

We extend a warm welcome to Mr Imran Khan, the Prime Minister of Pakistan. He is a truly inspirational individual who was undoubtedly an excellent cricketer. Since retirement from cricket, he has decided to get involved in politics, and after several years of patiently building up his support base, he won the last parliamentary elections. I hope that just as much as he galvanized Sri Lankan cricketers, his political journey would act as a catalyst for people like Kumar Sangakkara and Mahela Jayawardene to get involved in politics. Cricket has been called a “gentleman’s game.” Whilst politics is far from it!.

Features

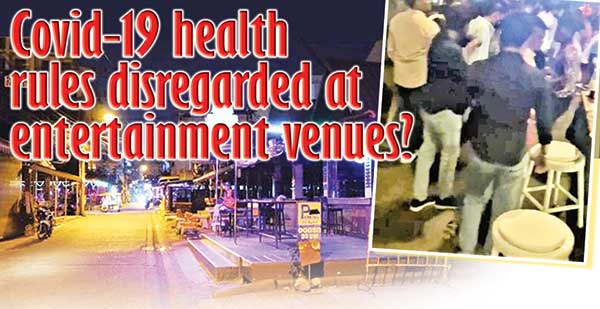

Covid-19 health rules disregarded at entertainment venues?

Believe me, seeing certain videos, on social media, depicting action, on the dance floor, at some of these entertainment venues, got me wondering whether this Coronavirus pandemic is REAL!

To those having a good time, at these particular venues, and, I guess, the management, as well, what the world is experiencing now doesn’t seem to be their concerned.

Obviously, such irresponsible behaviour could create more problems for those who are battling to halt the spread of Covid-19, and the new viriant of Covid, in our part of the world.

The videos, on display, on social media, show certain venues, packed to capacity – with hardly anyone wearing a mask, and social distancing…only a dream..

How can one think of social distancing while gyrating, on a dance floor, that is over crowded!

If this trend continues, it wouldn’t be a surprise if Coronavirus makes its presence felt…at such venues.

And, then, what happens to the entertainment scene, and those involved in this field, especially the musicians? No work, whatsoever!

Lots of countries have closed nightclubs, and venues, where people gather, in order to curtail the spread of this deadly virus that has already claimed the lives of thousands.

Thailand did it and the country is still having lots of restrictions, where entertainment is concerned, and that is probably the reason why Thailand has been able to control the spread of the Coronavirus.

With a population of over 69 million, they have had (so far), a little over 25,000 cases, and 83 deaths, while we, with a population of around 21 million, have over 80,000 cases, and more than 450 deaths.

I’m not saying we should do away with entertainment – totally – but we need to follow a format, connected with the ‘new normal,’ where masks and social distancing are mandatory requirements at these venues. And, dancing, I believe, should be banned, at least temporarily, as one can’t maintain the required social distance, while on the dance floor, especially after drinks.

Police spokesman DIG Ajith Rohana keeps emphasising, on TV, radio, and in the newspapers, the need to adhere to the health regulations, now in force, and that those who fail to do so would be penalised.

He has also stated that plainclothes officers would move around to apprehend such offenders.

Perhaps, he should instruct his officers to pay surprise visits to some of these entertainment venues.

He would certainly have more than a bus load of offenders to be whisked off for PCR/Rapid Antigen tests!

I need to quote what Dr. H.T. Wickremasinghe said in his article, published in The Island of Tuesday, February 16th, 2021:

“…let me conclude, while emphasising the need to continue our general public health measures, such as wearing masks, social distancing, and avoiding crowded gatherings, to reduce the risk of contact with an infected person.

“There is no science to beat common sense.”

But…do some of our folks have this thing called COMMON SENSE!