Features

Province unsuitable as a unit of governance

by Neville Ladduwahetty

The government is reportedly planning to hold the provincial council elections while an expert committee is actively engaged in the making of a new constitution. Holding elections before the drafting of a constitution imposes a constraint on the expert committee since it cannot afford to drift too far from existing arrangements if it is not to incur the ire of the elected members following an election. This means that the expert committee cannot take into account the prevailing antipathy towards Provincial Councils (PCs), for whatever reason, and propose a fresh approach to devolution

This would be the unfortunate outcome if elections to PCs are held prior to the promulgation of a new constitution. If elections are held after a new Constitution is in place, it will give the expert committee an opportunity to propose a fresh approach after taking into account the lessons of historical experiences Sri Lanka has had to endure. Therefore, the plea to the government is to give the country the opportunity to evolve a system of government that serves them best, free of constraints.

LESSONS OF HISTORY

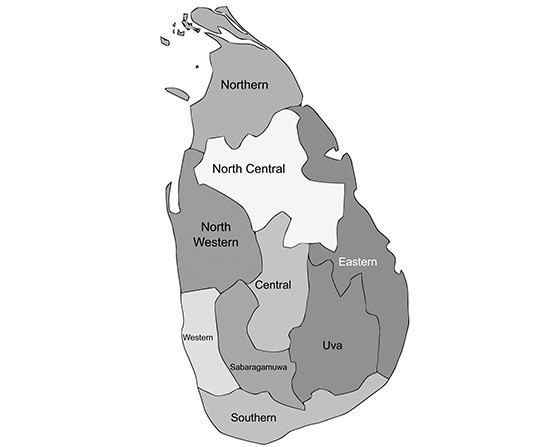

Having gained control of the whole of the island following the Kandyan Convention in 1815, the British attempted to administer the island as a single unit under a Governor. It did not take long for the British to realize that consolidation of power through an effective administration required the island to be sub-divided into smaller units as recommended by the Colebrooke-Cameron Reforms of 1833. The process of sub-division that started out with five (5) Provinces ended up with nine (9) provinces in 1889. Throughout this process of sub-division each province was further divided into districts and even smaller units in order to better administer the province. Thus by 1889 the nine provinces ended up being divided into the 25 districts.

With the introduction of the 13th Amendment to the Constitution in 1987, which created Provincial Councils, the lessons of history were ignored. Although the lesson of history was that smaller units are more effective as an administrative tool, the reversal to the larger unit of the province ignored the colonial guidelines of administration. The plea to the framers of the New Constitution is that these lessons of history are not ignored. What history has demonstrated clearly is that the province as a unit is ineffective as a unit of governance.

Although the administration of the island was based on the provinces under an all-powerful Government Agent for each province from 1833, his powers underwent significant derogation with the introduction of the Donoughmore Commission recommendations of 1931. Affirming this trend, the citation presented below states: “The status of the GA after the Donoughmore recommendations could be portrayed through the following note. ‘The division of government’s activities into ten ministries with a minister in charge of each activity, in place of general surveillance by the colonial secretary reduced enormously the power and responsibilities of the GA and led to the appointment of the departmental organizations responsible to the minister to manage many of the executives formerly entrusted to GA’. Thus the power and status of the GA, who was once an unquestioned authority in the district, underwent gradual erosion with the acquisition of his powers and authority of local administration by the departmental field agencies (Leitan p.41) Local administration for instance, under which Sanitary Boards and Village Committees were formerly supervised by the Kachchery organizations was now under the Department of Local Government. Education, Agriculture, Health and Public Works that were the subjects under the purview of the GA were the responsibilities of relevant departments under the executive committee system. (Ranasinghe R.A.W, “Role of Government Agent in Local Administration in Sri Lanka, International Journal of Education and Research, Vol. 2 No.2 February 2014).

Commenting on the process of division and sub-division during the colonial period where the powers of the provincial Government Agent become increasingly marginalized, Dr. Peiris in a characteristically scholarly article states: “Intra-provincial administrative adjustments were made at various times bringing the total number of Districts in the country from nineteen in 1889 to twenty-five at present. Government Agents of the provinces, holding executive power over their areas of authority, coordinated a range of government activities in their respective provinces. It is important to note, however, that in certain components of governance, while the related regional demarcations did not always coincide with provincial and district boundaries, the Government Agent had either only marginal involvement or no authority at all. This was particularly evident in fields such as the administration of justice, maintenance of law and order, and the provision of services in education and health care, in which there is large-scale daily interaction between the government and the people. (Dr. G.H. Peiris, Province-based Devolution in Sri Lanka: a Critique, December 17, 2020).

As Chairman of the Executive Committee responsible for Local Government it was Hon. S.W.R.D. Bandaranaike in 1940 who advocated the district as the most suitable unit from a Local Government perspective. His recommendation to the State Council was: “though the word ‘provincial’ is used here, I would point out that this body would be restricted to a revenue district, not necessarily to a province as we have it now, but to a revenue district. The Galle District, the Matara District, the Nuwara Eliya District and so on…” (Hansard {State Council}, 10 July 1940, pp. 1362-1371).

Thus, the lesson of history confirms the unsuitability of the province by itself as a unit of administration /governance. It is the sub-division of the province to districts that made administration effective during the colonial period. Furthermore, even though the population in the island in 1889 was only three million (Dr. G.H. Peiris), if the colonial powers deemed it appropriate to structure the island into nine provinces and twenty-five districts for reasons of administration, what kind of logic would justify reverting back to the larger unit of the province when the population is more than nearly six times what it was in 1889?

The reason for the reversal to the province was definitely NOT motivated by governance. The motivation for the reversal was clearly political. It was triggered by the need to find a solution to the Tamil national question based on claims of a traditional homeland involving the Northern and Eastern Provinces following the riots of 1983 and the intervention of India under the guise of the Indo-Lanka Accord. The history lesson that had come from colonial times to recognize the district and sub-divisions of the district, was ignored. What was introduced instead, was the province as the unit of governance in 1987, under the 13th Amendment. It is therefore understandable why the reversal to a province is as unworkable today as had been recognized by the colonial rulers.

LEARNING from HISTORY

No amount of additional powers and resources would make the provincial council system work, because the intention of the arrangement was for all power to be retained by the provincial councils. Such a centralized top down approach is inherently unworkable; a lesson the colonial administrators had eventually learnt. The only way to make it work was to devolve powers from the province to districts and to sub-divisions of districts such as pradeshiya sabhas and other local government units. This would derogate the powers currently exercised by the Chief Minister and the provincial council. Consequently, it would not be any different to the erosion of the powers of colonial Government Agents (GA) until the Donoughmore Commission recommendations were implemented and districts and its sub-units directly handled peripheral issues, thereby underscoring the irrelevance of the GA. Therefore, there is little or no prospect of PCs elected under current provisions devolving powers to districts and local governments within the province. Consequently, the current ineffective arrangements under the 13th Amendment would continue unless transformed rationally.

Although the province lost its relevance from an administration perspective, the British continued to identify the territory of the island in terms of provinces and districts. Even independent Ceylon and the Republic of Sri Lanka continued to identify the territory in terms of provinces and districts. However, it was only Article 5 of the 1978 Constitution that identified the territory of the Republic in terms of the district.

Notwithstanding the identification of the territory of the Republic of Sri Lanka in terms of the district, the reference to province resurfaced following the Vaddukoddai Resolution of 1976 that called for a separate state involving the Northern and Eastern Provinces. With this and the three-decade long armed conflict to create a separate state, the province has once more assumed importance to the point of not only becoming a threat to the territorial integrity of Sri Lanka, but also bequeathed an administrative nightmare that needs to be addressed without any further delay.

That nightmare is that every province in Sri Lanka functions under two parallel systems. One system administers functions relating to line ministries of the central government and a second system administers functions relating to the powers devolved to the provinces under the 13th Amendment. Reverting back to the decentralized system that existed prior to devolution is not a satisfactory arrangement either, because of the remoteness of the center from the priorities of the periphery. Devolving power to the provinces is akin to a centralized arrangement because it is as remote from the periphery. The problem with the current arrangement is not so much due to the two parallel systems, but primarily due to the choice of the unit to which power is devolved. Therefore, accepting that two parallel systems need to function concurrently because of its

in-built merit that power needs to be shared, one way to mitigate its negative aspects is to devolve appropriate power to districts and the local government entities in keeping with the concept of subsidiarity, instead of the provinces as exists today.

POSSIBLE OPTIONS

The choice for the Government is either to live with the current ineffective arrangement as per the 13th Amendment despite the denial of human rights of the overwhelming majority for improved governance, or actively promote a change to current arrangements notwithstanding a possible backlash from those who benefit from current arrangements.

One way to mitigate a possible backlash would be to absorb all the elected members in each PC into a District- based Council and divide the powers currently devolved under the 13th Amendment excluding powers relating to Law and Order, Land and Land Settlement and any others based on the concept of subsidiarity between such District-based Councils and the Local Governments. Such an arrangement would empower the districts with powers it did not have and enhance the powers currently assigned to Local Governments. In addition, it would give many more members currently elected to PCs an opportunity to directly engage in District-level activities than they are today.

For instance, under the current PC system, on an average, only the Chief Minister and four others form the Board of Ministers in each of the nine provinces. This means a total of forty-five are actively engaged in all the nine provinces with the majority of the Council members not having an opportunity to play a meaningful role. Consequently, the arrangement is undemocratic since the majority of elected members do not have the opportunity to contribute their views and express their concerns. If as proposed herein, a five-member Board of Minister is created in each district a total of one hundred and twenty-five Councilors in the twenty-five districts would be in a position to engage themselves meaningfully. According to a website as of 2017 there were 455 PC members. Accommodating all of them in the 25 districts would mean each district-based council would have an average of 18 to 19 members. On the other hand, if the district-based council is made up of a minimum of 2 from each of the nearly 260 Pradheshiya Sabahs (not including the 14MCs and 37UCs) the number in the 25 district council would be 520 i.e. more than from all the PCs. Therefore, whether the district council is formed from members of PCs or from members of local governments, the numbers involved would be similar. The only difference being the cost of conducting an election to elect the district-based council. Therefore, regardless of how the district based council is elected, it is imperative that if Sri Lanka is to prosper it has to transfer powers currently devolved to the provinces to district-based councils and local government entities.

CONCLUSION

The Province as a territorial unit is of relevance to the Tamil political leadership, while it is of no relevance to the overwhelming majority of citizens. To the Tamil leadership the province provides them the opportunity to merge the Northern and Eastern Provinces and carve out a single political unit on grounds of a dubious Tamil homeland claim despite the absence of any physical vestige of such a claim. To the average citizen the province with all power vested in it, is an impediment to improved governance that affects his/her well-being. Furthermore, the province is an ever present and a constant threat to Sri Lanka’s territorial integrity and national security as demonstrated by a three-decade long armed conflict followed by continuing threats by the Tamil leadership to go it alone.

Although colonial administrators started out to govern the island by creating five provinces in 1833 under Colebrooke-Cameron Reforms, they soon realized that effective administration was not possible without creating more provinces along with districts within each province. This process continued until 1889, when the territory of colonial Ceylon was divided into nine provinces and twenty-five districts. However, with the introduction of Donoughmore Commission reforms the relevance of the Government Agent of the province and the province as an administrative tool gradually faded and the smaller unit of the district became the more effective territorial unit for effective governance. This trend is quoted in the references cited above. The district as the unit of administration was also recognized by the State Council for purposes of Local Government even prior to independence in 1940.

These lessons of history were ignored when power was devolved to provinces under the 13th Amendment to the Constitution in 1987. The true intent for resurrecting the province with political power was clearly political because it provided for the Northern and Eastern provinces to be merged into a single territorial unit to be governed by a single PC. For this to happen the province has to survive and its survival depends on how it delivers on governance. The fact that the province has failed as a viable devolved unit means that the province has lost its purpose and therefore the justification to exist.

If Sri Lanka is to prosper it is imperative that the province as a territorial and political entity is abolished for three vital reasons.

One – That powers devolved to the provinces under the 13th Amendments excluding Law and Order, Land and Land Settlement and any others based on the concept of subsidiarity, should be divided between the districts and related local governments with a view to facilitating greater economic development and for reasons of fostering enhanced democratic governance.

Two – That the province represents a clear and constant danger to Sri Lanka’s territorial integrity because its size tempts separatist aspirations.

Three – That because the province was created in order to meet political exigencies and not for reasons of good governance, the time and opportunity have come to abandon serving parochial political imaginings of a few and create a system that focuses on human development for the benefit of all citizens.

- News Advertiesment

See Kapruka’s top selling online shopping categories such as Toys, Grocery, Flowers, Birthday Cakes, Fruits, Chocolates, Clothing and Electronics. Also see Kapruka’s unique online services such as Money Remittence,News, Courier/Delivery, Food Delivery and over 700 top brands. Also get products from Amazon & Ebay via Kapruka Gloabal Shop into Sri Lanka.

Features

Islamophobia and the threat to democratic development

There’s an ill more dangerous and pervasive than the Coronavirus that’s currently sweeping Sri Lanka. That is the fear to express one’s convictions. Across the public sector of the country in particular many persons holding high office are stringently regulating and controlling the voices of their consciences and this bodes ill for all and the country.

The corrupting impact of fear was discussed in this column a couple of weeks ago when dealing with the military coup in Myanmar. It stands to the enduring credit of ousted Myanmarese Head of Government Aung San Suu Kyi that she, perhaps for the first time in the history of modern political thought, singled out fear, and not power, as the principal cause of corruption within the individual; powerful or otherwise.

To be sure, power corrupts but the corrupting impact of fear is graver and more devastating. For instance, the fear in a person holding ministerial office or in a senior public sector official, that he would lose position and power as a result of speaking out his convictions and sincere beliefs on matters of the first importance, would lead to a country’s ills going unaddressed and uncorrected.

Besides, the individual concerned would be devaluing himself in the eyes of all irrevocably and revealing himself to be a person who would be willing to compromise his moral integrity for petty worldly gain or a ‘mess of pottage’. This happens all the while in Lankan public life. Some of those who have wielded and are wielding immense power in Sri Lanka leave very much to be desired from these standards.

It could be said that fear has prevented Sri Lanka from growing in every vital respect over the decades and has earned for itself the notoriety of being a directionless country.

All these ills and more are contained in the current controversy in Sri Lanka over the disposal of the bodies of Covid victims, for example. The Sri Lankan polity has no choice but to abide by scientific advice on this question. Since authorities of the standing of even the WHO have declared that the burial of the bodies of those dying of Covid could not prove to be injurious to the wider public, the Sri Lankan health authorities could go ahead and sanction the burying of the bodies concerned. What’s preventing the local authorities from taking this course since they claim to be on the side of science? Who or what are they fearing? This is the issue that’s crying out to be probed and answered.

All these ills and more are contained in the current controversy in Sri Lanka over the disposal of the bodies of Covid victims, for example. The Sri Lankan polity has no choice but to abide by scientific advice on this question. Since authorities of the standing of even the WHO have declared that the burial of the bodies of those dying of Covid could not prove to be injurious to the wider public, the Sri Lankan health authorities could go ahead and sanction the burying of the bodies concerned. What’s preventing the local authorities from taking this course since they claim to be on the side of science? Who or what are they fearing? This is the issue that’s crying out to be probed and answered.

Considering the need for absolute truthfulness and honesty on the part of all relevant persons and quarters in matters such as these, the latter have no choice but to resign from their positions if they are prevented from following the dictates of their consciences. If they are firmly convinced that burials could bring no harm, they are obliged to take up the position that burials should be allowed.

If any ‘higher authority’ is preventing them from allowing burials, our ministers and officials are conscience-bound to renounce their positions in protest, rather than behave compromisingly and engage in ‘double think’ and ‘double talk’. By adopting the latter course they are helping none but keeping the country in a state of chronic uncertainty, which is a handy recipe for social instabiliy and division.

In the Sri Lankan context, the failure on the part of the quarters that matter to follow scientific advice on the burials question could result in the aggravation of Islamophobia, or hatred of the practitioners of Islam, in the country. Sri Lanka could do without this latter phobia and hatred on account of its implications for national stability and development. The 30 year war against separatist forces was all about the prevention by military means of ‘nation-breaking’. The disastrous results for Sri Lanka from this war are continuing to weigh it down and are part of the international offensive against Sri Lanka in the UNHCR.

However, Islamophobia is an almost world wide phenomenon. It was greatly strengthened during Donald Trump’s presidential tenure in the US. While in office Trump resorted to the divisive ruling strategy of quite a few populist authoritarian rulers of the South. Essentially, the manoeuvre is to divide and rule by pandering to the racial prejudices of majority communities.

It has happened continually in Sri Lanka. In the initial post-independence years and for several decades after, it was a case of some populist politicians of the South whipping-up anti-Tamil sentiments. Some Tamil politicians did likewise in respect of the majority community. No doubt, both such quarters have done Sri Lanka immeasurable harm. By failing to follow scientific advice on the burial question and by not doing what is right, Sri Lanka’s current authorities are opening themselves to the charge that they are pandering to religious extremists among the majority community.

The murderous, destructive course of action adopted by some extremist sections among Muslim communities world wide, including of course Sri Lanka, has not earned the condemnation it deserves from moderate Muslims who make-up the preponderant majority in the Muslim community. It is up to moderate opinion in the latter collectivity to come out more strongly and persuasively against religious extremists in their midst. It will prove to have a cementing and unifying impact among communities.

It is not sufficiently appreciated by governments in the global South in particular that by voicing for religious and racial unity and by working consistently towards it, they would be strengthening democratic development, which is an essential condition for a country’s growth in all senses.

A ‘divided house’ is doomed to fall; this is the lesson of history. ‘National security’ cannot be had without human security and peaceful living among communities is central to the latter. There cannot be any ‘double talk’ or ‘politically correct’ opinions on this question. Truth and falsehood are the only valid categories of thought and speech.

Those in authority everywhere claiming to be democratic need to adopt a scientific outlook on this issue as well. Studies conducted on plural societies in South Asia, for example, reveal that the promotion of friendly, cordial ties among communities invariably brings about healing among estranged groups and produces social peace. This is the truth that is waiting to be acted upon.

Features

Pakistan’s love of Sri Lanka

By Sanjeewa Jayaweera

It was on 3rd January 1972 that our family arrived in Karachi from Moscow. Our departure from Moscow had been delayed for a few weeks due to the military confrontation between Pakistan and India. It ended on 16th December 1971. After that, international flights were not permitted for some time.

The contrast between Moscow and Karachi was unbelievable. First and foremost, Moscow’s temperature was near minus 40 degrees centigrade, while in Karachi, it was sunny and a warm 28 degrees centigrade. However, what struck us most was the extreme warmth with which the airport authorities greeted our family. As my father was a diplomat, we were quickly ushered to the airport’s VIP Lounge. We were in transit on our way to Rawalpindi, the airport serving the capital of Islamabad.

We quickly realized that the word “we are from Sri Lanka” opened all doors just as saying “open sesame” gained entry to Aladdin’s cave! The broad smile, extreme courtesy, and genuine warmth we received from the Pakistani people were unbelievable.

This was all to do with Mrs Sirima Bandaranaike’s decision to allow Pakistani aircraft to land in Colombo to refuel on the way to Dhaka in East Pakistan during the military confrontation between Pakistan and India. It was a brave decision by Mrs Bandaranaike (Mrs B), and the successive governments and Sri Lanka people are still enjoying the fruits of it. Pakistan has been a steadfast and loyal supporter of our country. They have come to our assistance time and again in times of great need when many have turned their back on us. They have indeed been an “all-weather” friend of our country.

Getting back to 1972, I was an early beneficiary of Pakistani people’s love for Sri Lankans. I failed the entrance exam to gain entry to the only English medium school in Islamabad! However, when I met the Principal, along with my father, he said, “Sanjeewa, although you failed the entrance exam, I will this time make an exception as Sri Lankans are our dear friends.” After that, the joke around the family dinner table was that I owed my education in Pakistan to Mrs B!

At school, my brother and I were extended a warm welcome and always greeted “our good friends from Sri Lanka.” I felt when playing cricket for our college; our runs were cheered more loudly than of others.

One particular incident that I remember well was when the Embassy received a telex from the Foreign inistry. It requested that our High Commissioner seek an immediate meeting with the Prime Minister of Pakistan, Mr Zulifikar Ali Bhutto (ZB), and convey a message from Mrs B. The message requested that an urgent shipment of rice be dispatched to Sri Lanka as there would be an imminent rice shortage. As the Ambassador was not in the station, the responsibility devolved on my father.

It usually takes about a week or more to get an audience with the Prime Minister (PM) of a foreign country due to their busy schedule. However, given the urgency, my father spoke to the Foreign Ministry’s Permanent Sectary, who fortunately was our neighbour and sought an urgent appointment. My father received a call from the PM’s secretary around 10 P.M asking him to come over to the PM’s residence. My father met ZB around midnight. ZB was about to retire to bed and, as such, was in his pyjamas and gown enjoying a cigar! He had greeted my father and had asked, “Mr Jayaweera, what can we do for great friend Madam Bandaranaike?. My father conveyed the message from Colombo and quietly mentioned that there would be riots in the country if there is no rice!

ZB had immediately got the Food Commissioner of Pakistan on the line and said, “I want a shipload of rice to be in Colombo within the next 72 hours!” The Food Commissioner reverted within a few minutes, saying that nothing was available and the last export shipment had left the port only a few hours ago to another country. ZB had instructed to turn the ship around and send it to Colombo. This despite protests from the Food Commissioner about terms and conditions of the Letter of Credit prohibiting non-delivery. Sri Lanka got its delivery of rice!

The next was the visit of Mrs B to Pakistan. On arrival in Rawalpindi airport, she was given a hero’s welcome, which Pakistan had previously only offered to President Gaddafi of Libya, who financially backed Pakistan with his oil money. That day, I missed school and accompanied my parents to the airport. On our way, we witnessed thousands of people had gathered by the roadside to welcome Mrs B.

When we walked to the airport’s tarmac, thousands of people were standing in temporary stands waving Sri Lanka and Pakistan flags and chanting “Sri Lanka Pakistan Zindabad.” The noise emanating from the crowd was as loud and passionate as the cheering that the Pakistani cricket team received during a test match. It was electric!

I believe she was only the second head of state given the privilege of addressing both assemblies of Parliament. The other being Gaddafi. There was genuine affection from Mrs B amongst the people of Pakistan.

I always remember the indefatigable efforts of Mr Abdul Haffez Kardar, a cabinet minister and the President of the Pakistan Cricket Board. From around 1973 onwards, he passionately championed Sri Lanka’s cause to be admitted as a full member of the International Cricket Council (ICC) and granted test status. Every year, he would propose at the ICC’s annual meeting, but England and Australia’s veto kept us out until 1981.

I always felt that our Cricket Board made a mistake by not inviting Pakistan to play our inaugural test match. We should have appreciated Mr Kardar and Pakistan’s efforts. In 1974 the Pakistan board invited our team for a tour involving three test matches and a few first-class games. Most of those who played in our first test match was part of that tour, and no doubt gained significant exposure playing against a highly talented Pakistani team.

Several Pakistani greats were part of the Pakistan and India team that played a match soon after the Central Bank bomb in Colombo to prove that it was safe to play cricket in Colombo. It was a magnificent gesture by both Pakistan and India. Our greatest cricket triumph was in Pakistan when we won the World Cup in 1996. I am sure the players and those who watched the match on TV will remember the passionate support our team received that night from the Pakistani crowd. It was like playing at home!

I also recall reading about how the Pakistani government air freighted several Multi Barrell artillery guns and ammunition to Sri Lanka when the A rmy camp in Jaffna was under severe threat from the LTTE. This was even more important than the shipload of rice that ZB sent. This was crucial as most other countries refused to sell arms to our country during the war.

Time and again, Pakistan has steadfastly supported our country’s cause at the UNHCR. No doubt this year, too, their diplomats will work tirelessly to assist our country.

We extend a warm welcome to Mr Imran Khan, the Prime Minister of Pakistan. He is a truly inspirational individual who was undoubtedly an excellent cricketer. Since retirement from cricket, he has decided to get involved in politics, and after several years of patiently building up his support base, he won the last parliamentary elections. I hope that just as much as he galvanized Sri Lankan cricketers, his political journey would act as a catalyst for people like Kumar Sangakkara and Mahela Jayawardene to get involved in politics. Cricket has been called a “gentleman’s game.” Whilst politics is far from it!.

Features

Covid-19 health rules disregarded at entertainment venues?

Believe me, seeing certain videos, on social media, depicting action, on the dance floor, at some of these entertainment venues, got me wondering whether this Coronavirus pandemic is REAL!

To those having a good time, at these particular venues, and, I guess, the management, as well, what the world is experiencing now doesn’t seem to be their concerned.

Obviously, such irresponsible behaviour could create more problems for those who are battling to halt the spread of Covid-19, and the new viriant of Covid, in our part of the world.

The videos, on display, on social media, show certain venues, packed to capacity – with hardly anyone wearing a mask, and social distancing…only a dream..

How can one think of social distancing while gyrating, on a dance floor, that is over crowded!

If this trend continues, it wouldn’t be a surprise if Coronavirus makes its presence felt…at such venues.

And, then, what happens to the entertainment scene, and those involved in this field, especially the musicians? No work, whatsoever!

Lots of countries have closed nightclubs, and venues, where people gather, in order to curtail the spread of this deadly virus that has already claimed the lives of thousands.

Thailand did it and the country is still having lots of restrictions, where entertainment is concerned, and that is probably the reason why Thailand has been able to control the spread of the Coronavirus.

With a population of over 69 million, they have had (so far), a little over 25,000 cases, and 83 deaths, while we, with a population of around 21 million, have over 80,000 cases, and more than 450 deaths.

I’m not saying we should do away with entertainment – totally – but we need to follow a format, connected with the ‘new normal,’ where masks and social distancing are mandatory requirements at these venues. And, dancing, I believe, should be banned, at least temporarily, as one can’t maintain the required social distance, while on the dance floor, especially after drinks.

Police spokesman DIG Ajith Rohana keeps emphasising, on TV, radio, and in the newspapers, the need to adhere to the health regulations, now in force, and that those who fail to do so would be penalised.

He has also stated that plainclothes officers would move around to apprehend such offenders.

Perhaps, he should instruct his officers to pay surprise visits to some of these entertainment venues.

He would certainly have more than a bus load of offenders to be whisked off for PCR/Rapid Antigen tests!

I need to quote what Dr. H.T. Wickremasinghe said in his article, published in The Island of Tuesday, February 16th, 2021:

“…let me conclude, while emphasising the need to continue our general public health measures, such as wearing masks, social distancing, and avoiding crowded gatherings, to reduce the risk of contact with an infected person.

“There is no science to beat common sense.”

But…do some of our folks have this thing called COMMON SENSE!