Midweek Review

Recordings of the island’s history as seen by the compilers of the Mahavamsa

‘A man loses contact with reality if he is not surrounded by his books’ – Francois Mitterand

By Usvatte-aratchi

I was delighted to read Haris’ (GPSH de Silva) new book ‘Sri Lanka, a brief history based on the Mahavamsa and …of the British Governors’. Living as we do, embalmed in fake news and entombed by the SARS-CoV-2, it is a relief to read anything so fresh. It brings one into contact with reality. The pleasure was compounded because Haris, with another, is the oldest friend I have. I cherish the first meeting with Haris on the corridor of Ramanathan Hall overlooking the river. I was walking to my room, lonely and forlorn, when a fellow freshman accosted me, ‘I am Haris. Who are you?’ (Well, I am not a historian but a plain Jane economist, no not even an economic historian!) I was the first entrant from my school to the university and here was a stranger, friendly. I was full of remorse when I failed to find Haris in Victoria Station, when both of us happened to be in London in 1963. I was away for most of my adult life but we saw each other every time I came back home. Because of our growing disabilities we have, in fact, not seen each for several months. His new book was a most welcome emissary.

It is a straight forward record of rulers in this land from the second century BCE (before the beginning of the Common Era). He was ‘dealing with the recordings of the island’s history, as seen by the compilers of the Mahavamsa…to jog the interest of the general reader as well as some students of history…’. It is brief, indeed, a mere 148 pages, including a bibliography. Among the entrants to our universities are many students who have never read any history after Grade 8 or 9, and that most unsatisfactorily. They will graduate with little familiarity with even an outline of the history of the island and even less of its literature. Without glorifying that which requires sober assessment, this little book may help to interest young people in what happened in the far past as well as in the near past of the people of this land. There is a lot of snake oil on this subject that is sold by interested parties. Here is the genuine stuff as is recorded in the old book of recipes, the Mahavamsa. It is small enough to fit in a back pocket of a person, as Haris was fond of doing when he was an undergraduate. It makes a nice gift to anyone interested in or might benefit from some familiarity with the history of this island.

It is not a history of the people but a list of rulers as presented in ‘chronological order’ but nor is Mahavamsa, as made clear by Haris. There are some brief notes about major events, especially those of a religious nature and those having to do with irrigation. Once reservoirs were built and irrigations system well established, life seems to have gone on with a certain degree of monotony. Mahavamsa does not tarry with even the momentous changes in religious beliefs and practices brought forth with the Chola invasions. However, with the introductory chapter in this book the ambitious reader can obtain some ideas about the life of the people. The author’s useful reference to epigraphical and archeological evidence helps out to imagine what may have been life in those days. From the account of British governors covering 41 pages, compared to the 100 pages for all rulers from the beginning, we learn of the innovations in transport, communications and other government activity. Perhaps, there is more written information on these besides what was given in the Mahavamsa. In the introduction, Haris has commented as follows: ‘Beyond religion, religious architecture, irrigation and literary works, evidence for (of?) dedicated scientific research on natural phenomena or any other worldly subjects is hard to come by…..Apart from the political history, it is seen, that, say unlike the ancient Greeks or ancient Chinese, the Sinhalese had not generally interested themselves in any scientific inquiries, concerning nature or natural history;..’. If one reads the literary works from amavatura to kusa jataka kavyaya, it is evident that the philosophy of knowledge (epistemology) that the Sinhala espoused, constricted themselves to works in the nature of atthakatha and tika on Buddhist teachings. The exceptions are the sandesa poems of the 15th century. (This is well written up in Rapiel Tennakone, ‘ape parani asun kavi’.)

At the end of the book, there is an appendix which gives the names of kings and their regnal years from Vijaya to Srivikrama Rajasingha and the Portuguese captains-General. The first list of names was published by Polwatte Buddhadattta (1959) in his Pali Mahavamso. The second list was written by K.M. de Silva in his A history of Sri Lanka(2005). Now we have a third in this book. It might be interesting to compare the lists but I cannot spare the time. My interest was aroused in an examination of the names of kings in the several periods of history, so divided by the principal capitals. When kings ruled from Anuradhapura there were three names for kings, that occurred frequently: Aba (abhaya), Tissa and Naga. Examples are panduka+abhaya, devanampiya tissa and chora+naga. When the capital moved to Polonnaruva, a new epithet appears frequently: Vijayabahu, parakramabahu, buvanekabahu. That tradition goes all the way down to Kotte. The bahu ending raises a question. Is it a different form for abhaya or aba? (Perakum+ba sirita has golu+aba for Gotabaya.) What does bhaya (fear, danger or risk) otherwise mean or signify? From Sitavaka began Rajasingha and the Sinhale monarchy ended in Maha nuvara with Sri Vickrema Rajasingha. What accounts for those changes and what do those changes signify? Haris did not set out asking those questions but they are not irrelevant.

After reading the book, three questions arose in my mind. The first, I raised in the previous paragraph. The third is in the last paragraph. The second is why did the Mahavamsa remain out of reach for the Sinhala reader for 14 centuries? In fact, it was read in French and English before it was read in Sinhala. The language of the Mahavamsa simply denied the expectation of its author ‘sujanappasada sangvegatthaya kathe mahavamso.- written for the enjoyment of the good people, as the sujana had no access to what he wrote. Haris has a short discussion on the language of the Mahavamsa but this is not one of the questions he raised; perhaps, it was not a subject fit for historical inquiry; I am not limited by that constraint. It is mentioned in the book itself, ‘Thera Mahanama, who compiled the earliest part from Cap 1 to Cap 37.52, was supposed to have used Sihalatthakatha Mahavamsa as the main source …’ Adikaram mentioned 19 sihalatthakatha that existed before Mahavamsa came to be written. Yet Mahavamsa was written in what Tennekone called bambabasa (the language of the brahmas) with which almost all people were unfamiliar. Did Mahanama want only bhikkhu and a few privileged laymen to have access to what he wrote? Then why were the motives of sihalatthakatha compilers, who came before him, different from those of Mahanama?

Perhaps, the answer is in the intervention of Buddhaghosha, who lived not far earlier than when Mahanama wrote the Mahavamsa. Malalasekera tells us that Buddhaghosha, collected all sihalatthakatha into a pile high as three fully grown elephants and set fire to them all. Buddhaghosha himself wrote his commentaries in Pali. Like all vanities, it was thought that writing in Pali exhibited one’s learning and writing in Sinhala was below the dignity of any man of learning. You can see that attitude among writers after Anuradhapura with the onset of Hindu and Samskritc cultural norms, well exhibited in Angkorvat and in Java. As I once pointed in this newspaper, it is remarkable that between the 5th century, up to which there had been Sinhala writings, Sinhala writing dried up until the 13th, excepting when in the 9th century Siyabaslakara, Dham piya atuva getapadaya and Sikha valanda (and vinisa) appeared, all of them samskrt and pali than Sinhala. A new Sinhala literature began at the end of the 13th century, when Lilavathie was queen, after a long eight centuries of drought.

The production of this book has been an amateur job by the publisher. There seems to have been no attention to book design, no copy editing and entirely inadequate proof reading. There are copy editing, grammar checks and spelling checks programmes which are common ware in computers now. No attempts seem to have been made to make use of those in preparing the typescript for print. I interrupted reading Rapiel Tennakone’s ape parani asun kavi running into 1175 pages, when I received Haris’ thin volume. Tennekone’s book has 350 pages of index, most taxing work. It was published in 1960 or so by M.D. Gunasena . The entire massive volume must have ben written by hand and proof-read several times over. I had read up to page 497 and had not found one error. There is responsible publishing. An author writes a book with labour and by the time he reads the typescript for the fifth time, there are no mistakes in it at all. However, when the fresh smelling copies come home, you feel it would have been better that you had not written. I am not trying to vent my spleen on this publisher but this malady is of epidemic proportions and the best-known publishers in the country publish fine authors with error filled volumes. I reviewed in these pages a few months ago a large volume and was furious that the publishers got away with scores of errors. It is time that our publishers took a lesson or two from those that came before them and from publishers overseas.

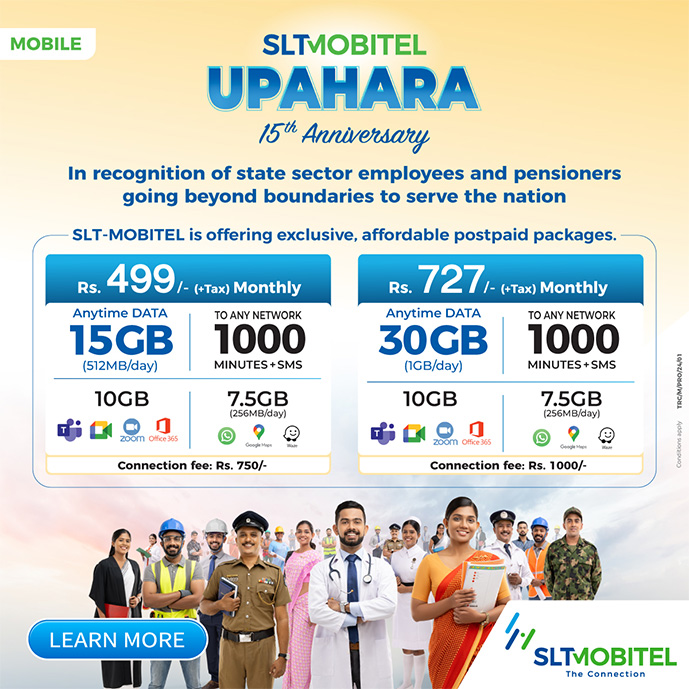

- News Advertiesment

See Kapruka’s top selling online shopping categories such as Toys, Grocery, Flowers, Birthday Cakes, Fruits, Chocolates, Clothing and Electronics. Also see Kapruka’s unique online services such as Money Remittence,News, Courier/Delivery, Food Delivery and over 700 top brands. Also get products from Amazon & Ebay via Kapruka Gloabal Shop into Sri Lanka.

Midweek Review

‘Professor of English Language Teaching’

It is a pleasure to be here today, when the University resumes postgraduate work in English and Education which we first embarked on over 20 years ago. The presence of a Professor on English Language Teaching from Kelaniya makes clear that the concept has now been mainstreamed, which is a cause for great satisfaction.

Twenty years ago, this was not the case. Our initiative was looked at askance, as indeed was the initiative which Prof. Arjuna Aluwihare engaged in as UGC Chairman to make degrees in English more widely available. Those were the days in which the three established Departments of English in the University system, at Peradeniya and Kelaniya and Colombo, were unbelievably conservative. Their contempt for his efforts made him turn to Sri Jayewardenepura, which did not even have a Department of English then and only offered it as one amongst three subjects for a General Degree.

Twenty years ago, this was not the case. Our initiative was looked at askance, as indeed was the initiative which Prof. Arjuna Aluwihare engaged in as UGC Chairman to make degrees in English more widely available. Those were the days in which the three established Departments of English in the University system, at Peradeniya and Kelaniya and Colombo, were unbelievably conservative. Their contempt for his efforts made him turn to Sri Jayewardenepura, which did not even have a Department of English then and only offered it as one amongst three subjects for a General Degree.

Ironically, the most dogmatic defence of this exclusivity came from Colombo, where the pioneer in English teaching had been Prof. Chitra Wickramasuriya, whose expertise was, in fact, in English teaching. But her successor, when I tried to suggest reforms, told me proudly that their graduates could go on to do postgraduate degrees at Cambridge. I suppose that, for generations brought up on idolization of E. F. C. Ludowyke, that was the acme of intellectual achievement.

I should note that the sort of idealization of Ludowyke, the then academic establishment engaged in was unfair to a very broadminded man. It was the Kelaniya establishment that claimed that he ‘maintained high standards, but was rarefied and Eurocentric and had an inhibiting effect on creative writing’. This was quite preposterous coming from someone who removed all Sri Lankan and other post-colonial writing from an Advanced Level English syllabus. That syllabus, I should mention, began with Jacobean poetry about the cherry-cheeked charms of Englishwomen. And such a characterization of Ludowyke totally ignored his roots in Sri Lanka, his work in drama which helped Sarachchandra so much, and his writing including ‘Those Long Afternoons’, which I am delighted that a former Sabaragamuwa student, C K Jayanetti, hopes to resurrect.

I have gone at some length into the situation in the nineties because I notice that your syllabus includes in the very first semester study of ‘Paradigms in Sri Lankan English Education’. This is an excellent idea, something which we did not have in our long-ago syllabus. But that was perhaps understandable since there was little to study then except a history of increasing exclusivity, and a betrayal of the excuse for getting the additional funding those English Departments received. They claimed to be developing teachers of English for the nation; complete nonsense, since those who were knowledgeable about cherries ripening in a face were not likely to move to rural areas in Sri Lanka to teach English. It was left to the products of Aluwihare’s initiative to undertake that task.

Another absurdity of that period, which seems so far away now, was resistance to training for teaching within the university system. When I restarted English medium education in the state system in Sri Lanka, in 2001, and realized what an uphill struggle it was to find competent teachers, I wrote to all the universities asking that they introduce modules in teacher training. I met condign refusal from all except, I should note with continuing gratitude, from the University of Sri Jayewardenepura, where Paru Nagasunderam introduced it for the external degree. When I started that degree, I had taken a leaf out of Kelaniya’s book and, in addition to English Literature and English Language, taught as two separate subjects given the language development needs of students, made the third subject Classics. But in time I realized that was not at all useful. Thankfully, that left a hole which ELT filled admirably at the turn of the century.

The title of your keynote speaker today, Professor of English Language Teaching, is clear evidence of how far we have come from those distant days, and how thankful we should be that a new generation of practical academics such as her and Dinali Fernando at Kelaniya, Chitra Jayatilleke and Madhubhashini Ratnayake at USJP and the lively lot at the Postgraduate Institute of English at the Open University are now making the running. I hope Sabaragamuwa under its current team will once again take its former place at the forefront of innovation.

To get back to your curriculum, I have been asked to teach for the paper on Advanced Reading and Writing in English. I worried about this at first since it is a very long time since I have taught, and I feel the old energy and enthusiasm are rapidly fading. But having seen the care with which the syllabus has been designed, I thought I should try to revive my flagging capabilities.

However, I have suggested that the university prescribe a textbook for this course since I think it is essential, if the rounded reading prescribed is to be done, that students should have ready access to a range of material. One of the reasons I began while at the British Council an intensive programme of publications was that students did not read round their texts. If a novel was prescribed, they read that novel and nothing more. If particular poems were prescribed, they read those poems and nothing more. This was especially damaging in the latter case since the more one read of any poet the more one understood what he was expressing.

Though given the short notice I could not prepare anything, I remembered a series of school textbooks I had been asked to prepare about 15 years ago by International Book House for what were termed international schools offering the local syllabus in the English medium. Obviously, the appalling textbooks produced by the Ministry of Education in those days for the rather primitive English syllabus were unsuitable for students with more advanced English. So, I put together more sophisticated readers which proved popular. I was heartened too by a very positive review of these by Dinali Fernando, now at Kelaniya, whose approach to students has always been both sympathetic and practical.

I hope then that, in addition to the texts from the book that I will discuss, students will read other texts in the book. In addition to poetry and fiction the book has texts on politics and history and law and international relations, about which one would hope postgraduate students would want some basic understanding.

Similarly, I do hope whoever teaches about Paradigms in English Education will prescribe a textbook so that students will understand more about what has been going on. Unfortunately, there has been little published about this but at least some students will I think benefit from my book on English and Education: In Search of Equity and Excellence? which Godage & Bros brought out in 2016. And then there was Lakmahal Justified: Taking English to the People, which came out in 2018, though that covers other topics too and only particular chapters will be relevant.

The former book is bulky but I believe it is entertaining as well. So, to conclude I will quote from it, to show what should not be done in Education and English. For instance, it is heartening that you are concerned with ‘social integration, co-existence and intercultural harmony’ and that you want to encourage ‘sensitivity towards different cultural and linguistic identities’. But for heaven’s sake do not do it as the NIE did several years ago in exaggerating differences. In those dark days, they produced textbooks which declared that ‘Muslims are better known as heavy eaters and have introduced many tasty dishes to the country. Watalappam and Buriani are some of these dishes. A distinguished feature of the Muslims is that they sit on the floor and eat food from a single plate to show their brotherhood. They eat string hoppers and hoppers for breakfast. They have rice and curry for lunch and dinner.’ The Sinhalese have ‘three hearty meals a day’ and ‘The ladies wear the saree with a difference and it is called the Kandyan saree’. Conversely, the Tamils ‘who live mainly in the northern and eastern provinces … speak the Tamil language with a heavy accent’ and ‘are a close-knit group with a heavy cultural background’’.

And for heaven’s sake do not train teachers by telling them that ‘Still the traditional ‘Transmission’ and the ‘Transaction’ roles are prevalent in the classroom. Due to the adverse standard of the school leavers, it has become necessary to develop the learning-teaching process. In the ‘Transmission’ role, the student is considered as someone who does not know anything and the teacher transmits knowledge to him or her. This inhibits the development of the student.

In the ‘Transaction’ role, the dialogue that the teacher starts with the students is the initial stage of this (whatever this might be). Thereafter, from the teacher to the class and from the class to the teacher, ideas flow and interaction between student-student too starts afterwards and turns into a dialogue. From known to unknown, simple to complex are initiated and for this to happen, the teacher starts questioning.’

And while avoiding such tedious jargon, please make sure their command of the language is better than to produce sentences such as these, or what was seen in an English text, again thankfully several years ago:

Read the story …

Hello! We are going to the zoo. “Do you like to join us” asked Sylvia. “Sorry, I can’t I’m going to the library now. Anyway, have a nice time” bye.

So Syliva went to the zoo with her parents. At the entrance her father bought tickets. First, they went to see the monkeys

She looked at a monkey. It made a funny face and started swinging Sylvia shouted: “He is swinging look now it is hanging from its tail its marvellous”

“Monkey usually do that’

I do hope your students will not hang from their tails as these monkeys do.

Midweek Review

Little known composers of classical super-hits

By Satyajith Andradi

Quite understandably, the world of classical music is dominated by the brand images of great composers. It is their compositions that we very often hear. Further, it is their life histories that we get to know. In fact, loads of information associated with great names starting with Beethoven, Bach and Mozart has become second nature to classical music aficionados. The classical music industry, comprising impresarios, music publishers, record companies, broadcasters, critics, and scholars, not to mention composers and performers, is largely responsible for this. However, it so happens that classical music lovers are from time to time pleasantly struck by the irresistible charm and beauty of classical pieces, the origins of which are little known, if not through and through obscure. Intriguingly, most of these musical gems happen to be classical super – hits. This article attempts to present some of these famous pieces and their little-known composers.

Pachelbel’s Canon in D

The highly popular piece known as Pachelbel’s Canon in D constitutes the first part of Johann Pachelbel’s ‘Canon and Gigue in D major for three violins and basso continuo’. The second part of the work, namely the gigue, is rarely performed. Pachelbel was a German organist and composer. He was born in Nuremburg in 1653, and was held in high esteem during his life time. He held many important musical posts including that of organist of the famed St Stephen’s Cathedral in Vienna. He was the teacher of Bach’s elder brother Johann Christoph. Bach held Pachelbel in high regard, and used his compositions as models during his formative years as a composer. Pachelbel died in Nuremburg in 1706.

Pachelbel’s Canon in D is an intricate piece of contrapuntal music. The melodic phrases played by one voice are strictly imitated by the other voices. Whilst the basso continuo constitutes a basso ostinato, the other three voices subject the original tune to tasteful variation. Although the canon was written for three violins and continuo, its immense popularity has resulted in the adoption of the piece to numerous other combinations of instruments. The music is intensely soothing and uplifting. Understandingly, it is widely played at joyous functions such as weddings.

Jeremiah Clarke’s Trumpet Voluntary

The hugely popular piece known as ‘Jeremiah Clarke’s Trumpet Voluntary’ appeared originally as ‘ The Prince of Denmark’s March’ in Jeremiah Clarke’s book ‘ Choice lessons for the Harpsichord and Spinet’, which was published in 1700 ( Michael Kennedy; Oxford Dictionary of Music ). Sometimes, it has also been erroneously attributed to England’s greatest composer Henry Purcell (1659 – 1695 ) and called ‘Purcell’s Trumpet Voluntary (Percy A. Scholes ; Oxford Companion to Music). This brilliant composition is often played at joyous occasions such as weddings and graduation ceremonies. Needless to say, it is a piece of processional music, par excellence. As its name suggests, it is probably best suited for solo trumpet and organ. However, it is often played for different combinations of instruments, with or without solo trumpet. It was composed by the English composer and organist Jeremiah Clarke.

Jeremiah Clarke was born in London in 1670. He was, like his elder contemporary Pachelbel, a musician of great repute during his time, and held important musical posts. He was the organist of London’s St. Paul’s Cathedral and the composer of the Theatre Royal. He died in London in 1707 due to self – inflicted gun – shot injuries, supposedly resulting from a failed love affair.

Albinoni’s Adagio

The full title of the hugely famous piece known as ‘Albinoni’s Adagio’ is ‘Adagio for organ and strings in G minor’. However, due to its enormous popularity, the piece has been arranged for numerous combinations of instruments. It is also rendered as an organ solo. The composition, which epitomizes pathos, is structured as a chaconne with a brooding bass, which reminds of the inevitability and ever presence of death. Nonetheless, there is no trace of despondency in this ethereal music. On the contrary, its intense euphony transcends the feeling of death and calms the soul. The composition has been attributed to the Italian composer Tomaso Albinoni (1671 – 1750), who was a contemporary of Bach and Handel. However, the authorship of the work is shrouded in mystery. Michael Kennedy notes: “The popular Adagio for organ and strings in G minor owes very little to Albinoni, having been constructed from a MS fragment by the twentieth century Italian musicologist Remo Giazotto, whose copyright it is” (Michael Kennedy; Oxford Dictionary of Music).

Boccherini’s Minuet

The classical super-hit known as ‘Boccherini’s Minuet’ is quite different from ‘Albinoni’s Adagio’. It is a short piece of absolutely delightful music. It was composed by the Italian cellist and composer Luigi Boccherini. It belongs to his string quintet in E major, Op. 13, No. 5. However, due to its immense popularity, the minuet is performed on different combinations of instruments.

Boccherini was born in Lucca in 1743. He was a contemporary of Haydn and Mozart, and an elder contemporary of Beethoven. He was a prolific composer. His music shows considerable affinity to that of Haydn. He lived in Madrid for a considerable part of his life, and was attached to the royal court of Spain as a chamber composer. Boccherini died in poverty in Madrid in 1805.

Like numerous other souls, I have found immense joy by listening to popular classical pieces like Pachelbel’s Canon in D, Jeremiah Clarke’s Trumpet Voluntary, Albinoni’s Adagio and Boccherini’s Minuet. They have often helped me to unwind and get over the stresses of daily life. Intriguingly, such music has also made me wonder how our world would have been if the likes of Bach, Handel, Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, and Schubert had never lived. Surely, the world would have been immeasurably poorer without them. However, in all probability, we would have still had Pachelbel’s Canon in D, Jeremiah Clarke’s Trumpet Voluntary, Albinoni’s Adagio, and Boccherini’s Minuet, to cheer us up and uplift our spirits.

Midweek Review

The Tax Payer and the Tough

By Lynn Ockersz

The tax owed by him to Caesar,

Leaves our retiree aghast…

How is he to foot this bill,

With the few rupees,

He has scraped together over the months,

In a shrinking savings account,

While the fires in his crumbling hearth,

Come to a sputtering halt?

But in the suave villa next door,

Stands a hulk in shiny black and white,

Over a Member of the August House,

Keeping an eagle eye,

Lest the Rep of great renown,

Be besieged by petitioners,

Crying out for respite,

From worries in a hand-to-mouth life,

But this thought our retiree horrifies:

Aren’t his hard-earned rupees,

Merely fattening Caesar and his cohorts?