Midweek Review

‘Truth and Science’ has won the US presidential election;

will America win the world through it?

By Rohana R. Wasala

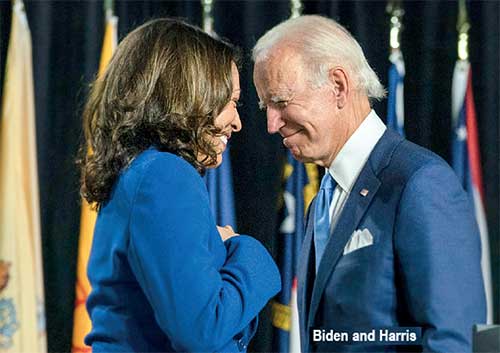

America is the most religious and the most nationalistic country in the world, in addition to being a global superpower. When the Democrats who fought the election on a platform of ‘Truth and Science’ defeated the Republicans who were guided or misguided by a person/a cult figure (instead of a coherent policy) whom many popular polls described as mendacious and ignorant on top of being an indecent narcissistic exemplar of religious and nationalistic extremism, racism and misogyny, it is natural for a world, persecuted by America’s hegemonic political economic and military power, to breathe a sigh of relief. Democratic Party’s Joe Biden and Kamala Harris have been declared President and Vice-President elects respectively, beating Republican Party’s Donald Trump, incumbent President, and his Vice-President and running mate Mike Pence. Sri Lanka is, no doubt, currently sharing that universal sense of consolation. Although some anti-national, NGO-dominated social media are trying in vain to turn that hopeful feeling to gloomy apprehension by drumming up a certain unfounded ‘Kamala Harris’ phobia, signs are that, probably, average Sri Lankans cannot wish a better person to be in that post to channel America’s influence in their region in a universally beneficent direction. My purpose here is to take a look at hypocritical religiosity and nationalism-turned-racism (versions of fundamentalist religion and racist jingoism, respectively), both at the service of despicable value-free politics, that Truth and Science successfully challenged at the recent US presidential election.

Religion is about human ‘spirituality’. Spirituality is ‘the quality of being concerned with the human spirit or soul as opposed to material or physical things’, in other words, with the mind as distinct from the body. So, it is appropriate to approach the phenomenon of religious fundamentalism from a psychological point of view. Some psychologists assume religious fundamentalism to be ‘a collection of infallible beliefs or principles that provide guidance regarding how to obtain salvation. Religious fundamentalists believe in the superiority of their religious teachings, and in a strict division between righteous people and evildoers…… This belief system regulates religious thoughts, but also all conceptions regarding the self, others, and the world’ (frontiers.org). Isn’t every religion fundamentalist by nature in this sense? But there are two kinds of religious fundamentalism in my opinion, harmless and harmful. What should concern us is the latter. The more a religion tends towards harmful religious fundamentalism, the more it resembles a cult that thrives on unhinged minds. A cult, we know, is ‘a system of religious veneration and devotion directed towards a particular figure or object’. (Both dictionary definitions given in this paragraph are from google.com)

The rise of Christian fundamentalism in America in the 19th century as a Protestant movement to counter theological liberalism and cultural modernism can be described as the advocacy of a return to the basic ‘infallible beliefs or principles ….’ of the Christian faith. That was harmless fundamentalism and was viewed as something positive. Actually, the term fundamentalism as originally applied to Christianity in America had non-violent, ‘you mind your own business, we mind ours’ connotations; the word acquired the current pejorative meaning in the media when it began to be connected with violent Islamic movements in the Middle East in the 1970s decade, a most conspicuous event among which was the 1979 Iran Revolution, that toppled the US-backed Shah of Iran, Mohamed Reza Pahlavi, during President Jimmy Carter’s last year in office. The latter, now 96, congratulated president elect Joe Biden and vice-president elect Kamala Harris as the media reported November 8.

Religious fundamentalism becomes a problem when any religion claims monopoly over

Truth (whatever that is), superiority over other faiths regardless of whether they also make similar claims about themselves, seeks to rescue the ‘misguided’ adherents of those faiths from allegedly false and evil beliefs and practices through coercion where conversion through conviction doesn’t work, or even resorts to violence to have its way with people, evoking divine authority to justify it. Religions are intrinsically political, but rarely democratically so. Religion and politics make a violently explosive mixture. (‘Politics has killed its thousands, but religion has slain its tens of thousands’. – Irish dramatist Sean O’Casey, ‘Religion kills’ ‘Religion poisons everything’ – British intellectual and socio-cultural and political critic Christopher Hitchens.) The Founding Fathers of the USA including Thomas Jefferson sought to establish a ‘wall of separation between the State and the Church’ to keep civil government free from the interferences of the Catholic clergy. The concept was termed ‘secularism’ only in the 19th century by British reformer George Jacob Holyoake.

Religious interference in what should come within exclusive state purview, for example public education, has persisted even into the third millennium, in America. A survey conducted in 2006 by Zogby International for the Discovery Institute found that approximately 70% of Americans approved of the view that biology teachers should teach Darwin’s theory of evolution, but also ‘the scientific evidence against it’ in contrast to 21% who held the opinion that only evolution and the scientific evidence that supports it must be taught in schools. This is the result of benighted ignorance – inexcusable in those who claim to be the greatest democracy and the only superpower in the world – that is at the root of religious fundamentalism. Evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins says that ‘the theory of evolution is actually a fact – as incontrovertible a fact as any in science’. There isn’t any scientific evidence against it. Prof. Dawkins makes ‘a personal summary of the evidence’ available to support this factual reality in his fascinating book ‘The Greatest Show on Earth’, Bantam Press, GB, 2009. The plain but profound final sentence of the book is worth quoting: ‘We are surrounded by endless forms, most beautiful and most wonderful, and it is no accident, but the direct consequence of evolution by non-random natural selection – the only game in town, the greatest show on Earth’.

In his book ‘Against Religion’ (Scribe Publications, Brunswick, VIC, Australia, 2007), Dr Tamas Pataki of the University of Melbourne makes a philosophical critique of religion, which goes beyond the neighbourhood of what, according to him, may be called psychology of religion. Pataki adopts religious scholar and philosopher John Haldane’s brief characterization of religion: ‘religion is best characterised as a system of beliefs and practices directed towards a transcendent reality in relation to which persons seek solutions to the observed facts of moral and physical evil, limitation and vulnerability, particularly and especially death.’

Scottish philosopher and academic John Haldane was a papal advisor to the Vatican. Obviously, he is not anti-religion; he is pro-religion.

He believes in the necessity of religion as a foundational political principle that fosters values like respect for others’ rights, and support for their well-being in multicultural multi-religious societies which are the global norm today for most countries; religion, according to him, is the best, and indeed, the only source of such ideas. Critics of religion argue that religions differ on what they consider to be moral and good, and instead of promoting goodwill and compassion towards people of other religions, sow feelings of mutual alienation, suspicion, and disunity, and egoistic self-absorption. Religious fundamentalism of both the benign and the malign kinds aggravate such attitudes.

According to Pataki, criticising religion is a complicated matter because there is so much diversity within religions. He writes: ‘The historical denominational differences are bad enough, but recent developments have completely erased any hope of perspicuous demarcation. Today the ineluctable longing for group identity drives even those who divest religion of its defining doctrinal content to religious affiliation. The denial of the Resurrection and the Deity is no bar to identifying as a Christian. Iris Murdoch (Irish British novelist and philosopher deeply concerned about good and evil) enjoined a Christianity without God or divine Jesus, a kind of Christian Buddhism. Unbelief has become belief.’

Pataki’s critical discussion is predicated on people that he describes as ‘religiose’, who include most of the groups currently identified as fundamentalist, among others. Another factor that forms an obstacle to criticism of religion is that it, like politics, cuts across a range of absolutely different fields: ideology/doctrine, practices, rituals, institutions, movements, attitudes, votaries, and priests. The evils of religion examined in the book are conspicuous in the three well known Abrahamic monotheisms, according to Pataki’s thinking.

Religion is not all bad, though, as already suggested. To many people religion is invaluable as the deepest expression of human worth and moral well-being. It is also an inexhaustible source of consolation for them in personally and socially distressful, emotionally draining situations such as bereavement and natural catastrophes. However, Pataki adds reservations to this: ‘There is no metric for religion at its best, but it is not hard to measure it at its worst, in the tenebrous collapse of reason and in corpses. Besides, it is obviously more important today to confront religion at its worst and most dangerous. The good takes care of itself.’ The further a religion is from blind irrationality and intrinsic violence, the greater is its potential as a socio-cultural institution for the general good of the community concerned.

Pataki describes ten characteristics of religious fundamentalism, which I will set down here – with my own elaborations given in parentheses, in some cases, as I understand them (Some of these were accidentally revealed during the US election): Religious fundamentalists are counter-modernists; they advocate religious, cultural and political isolationism; they are assertive, clamorous, and often violent, (but they play the victim card when confronted); fundamentalists believe that they are the Elect of their god, the Chosen people, the Saved, etc; they display public marks of distinction, which they think are necessary to maintain their superiority and distinctive identity (so, they may wear special body marks, adopt a special dress code, and use names that reveal their specific religious identity); religious fundamentalists believe that (as theirs is the one true religion and the one exclusively blameless way of life) these must not allow any inroads to be made into their domain from other religions (or secularist institutions, religious pluralism is unthinkable for them). A sixth characteristic belief that fundamentalists commonly share is that there is only one inerrant holy book, and one inerrant prophet or charismatic leader (both of which they have been divinely favoured with). They also believe that law and authority come from God and that God’s law surpasses human law. Yet another fundamentalist characteristic is the preoccupation with controlling female sexuality; unbreachable segregation must be established between men and women. Pataki identifies the ninth characteristic of fundamentalists as their major concern with the sexual behaviour of individuals; the fear of and opposition to homosexuality. The tenth characteristic of fundamentalists is that their religious fundamentalism is inseparable from their nationalism (nationalism of the evil kind, racism, the ‘all for ourselves and nothing for other people’ doctrine usually adopted by Americans that Noam Chomsky criticises in in his book ‘Who Rules the World’, 2016).

For me, evidence for the last point mentioned came from the tail end of Donald Trump’s election campaign. The nationalism slogan was loudly chanted on the stages of both camps, Democratic and Republican. There is nothing wrong with that. Good nationalism should be commended. Racism that passes for nationalism is what is bad. On the Republican side, the identity between the wrong kind of nationalism (white racism) and what can be described as religious fundamentalism in terms of the characteristics given above, was particularly conspicuous. Paula White, Trump’s spiritual adviser, held a number of prayer services invoking divine blessings for his victory even as his defeat had become a certainty by the final stages of the counting process which was still in progress in the wake of the just concluded presidential election. She, apparently, engaged in battle with the ‘demonic confederacies’ that were allegedly trying to steal Trump’s victory (cf. ‘a strict division between righteous people and evildoers’ in the second paragraph from the beginning of this essay). She loudly chanted: ‘Strike Strike…. I Strike the ground……..until you have Victory…..I hear a sound of Victory…I hear an overabundance of Rain and Victory in the Quarters of Heaven…..I hear Shouting and Singing…. Angels are being released……are being despatched…’ etc. Then she broke into speaking in tongues (directly communicating with God) like Paul did after Christ resurrected: ‘Amanda, Atha, Rasa, Baka, Ambo, Rike, Eka, Anda, Anda, Manda… I hear the sound of Victory, etc’. Trump lost in spite of all this. The Democrat Joe Biden, who, on his part, presumably, made as passionate a supplication for divine intervention for his victory, won the election. But his no nonsense main campaign slogan ‘Battle for the Soul of the Nation Our Best Days Still Lie Ahead No Malarkey! Build Back Better Unite for a Better America’ had little to do with religion.

When all is said and done, it is up to the American people, as Americans, to choose their ruler/s for the next four years; they are doing that now. On the face of it, especially to us outsiders, the winning margin of four million votes according to estimates at the time of writing (Biden’s 74 to Trump ‘s 70 million) is a bit disappointing; the gap should have been wider, we feel, given the unpopularity of the latter, deepened by the anti-Trump stance of the media and Trump’s own apparent personal perverseness, his unconcealed white supremacist bravado and his sexist prejudice displayed against his own near and dear ones. However, only his 70 million or more supporters know what endeared him to them. Outsiders cannot decide for Americans. The best we may expect from the incoming US administration is that they appreciate this reality in respect of Sri Lanka when considering whether or not to continue or modify the established tradition of intervention and interference in its affairs in pursuit of their geopolitical ends in its region as an essential part of their grand scheme of serving their own national interest back home.

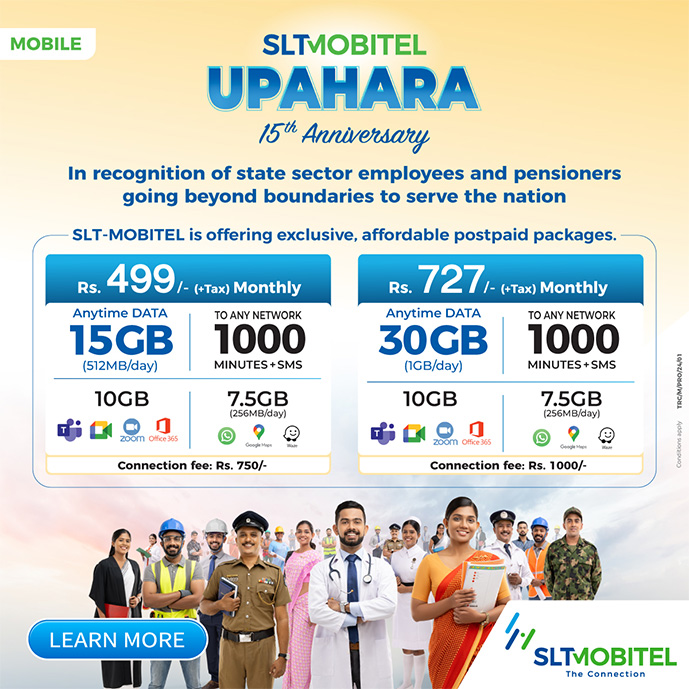

- News Advertiesment

See Kapruka’s top selling online shopping categories such as Toys, Grocery, Flowers, Birthday Cakes, Fruits, Chocolates, Clothing and Electronics. Also see Kapruka’s unique online services such as Money Remittence,News, Courier/Delivery, Food Delivery and over 700 top brands. Also get products from Amazon & Ebay via Kapruka Gloabal Shop into Sri Lanka.

Midweek Review

‘Professor of English Language Teaching’

It is a pleasure to be here today, when the University resumes postgraduate work in English and Education which we first embarked on over 20 years ago. The presence of a Professor on English Language Teaching from Kelaniya makes clear that the concept has now been mainstreamed, which is a cause for great satisfaction.

Twenty years ago, this was not the case. Our initiative was looked at askance, as indeed was the initiative which Prof. Arjuna Aluwihare engaged in as UGC Chairman to make degrees in English more widely available. Those were the days in which the three established Departments of English in the University system, at Peradeniya and Kelaniya and Colombo, were unbelievably conservative. Their contempt for his efforts made him turn to Sri Jayewardenepura, which did not even have a Department of English then and only offered it as one amongst three subjects for a General Degree.

Twenty years ago, this was not the case. Our initiative was looked at askance, as indeed was the initiative which Prof. Arjuna Aluwihare engaged in as UGC Chairman to make degrees in English more widely available. Those were the days in which the three established Departments of English in the University system, at Peradeniya and Kelaniya and Colombo, were unbelievably conservative. Their contempt for his efforts made him turn to Sri Jayewardenepura, which did not even have a Department of English then and only offered it as one amongst three subjects for a General Degree.

Ironically, the most dogmatic defence of this exclusivity came from Colombo, where the pioneer in English teaching had been Prof. Chitra Wickramasuriya, whose expertise was, in fact, in English teaching. But her successor, when I tried to suggest reforms, told me proudly that their graduates could go on to do postgraduate degrees at Cambridge. I suppose that, for generations brought up on idolization of E. F. C. Ludowyke, that was the acme of intellectual achievement.

I should note that the sort of idealization of Ludowyke, the then academic establishment engaged in was unfair to a very broadminded man. It was the Kelaniya establishment that claimed that he ‘maintained high standards, but was rarefied and Eurocentric and had an inhibiting effect on creative writing’. This was quite preposterous coming from someone who removed all Sri Lankan and other post-colonial writing from an Advanced Level English syllabus. That syllabus, I should mention, began with Jacobean poetry about the cherry-cheeked charms of Englishwomen. And such a characterization of Ludowyke totally ignored his roots in Sri Lanka, his work in drama which helped Sarachchandra so much, and his writing including ‘Those Long Afternoons’, which I am delighted that a former Sabaragamuwa student, C K Jayanetti, hopes to resurrect.

I have gone at some length into the situation in the nineties because I notice that your syllabus includes in the very first semester study of ‘Paradigms in Sri Lankan English Education’. This is an excellent idea, something which we did not have in our long-ago syllabus. But that was perhaps understandable since there was little to study then except a history of increasing exclusivity, and a betrayal of the excuse for getting the additional funding those English Departments received. They claimed to be developing teachers of English for the nation; complete nonsense, since those who were knowledgeable about cherries ripening in a face were not likely to move to rural areas in Sri Lanka to teach English. It was left to the products of Aluwihare’s initiative to undertake that task.

Another absurdity of that period, which seems so far away now, was resistance to training for teaching within the university system. When I restarted English medium education in the state system in Sri Lanka, in 2001, and realized what an uphill struggle it was to find competent teachers, I wrote to all the universities asking that they introduce modules in teacher training. I met condign refusal from all except, I should note with continuing gratitude, from the University of Sri Jayewardenepura, where Paru Nagasunderam introduced it for the external degree. When I started that degree, I had taken a leaf out of Kelaniya’s book and, in addition to English Literature and English Language, taught as two separate subjects given the language development needs of students, made the third subject Classics. But in time I realized that was not at all useful. Thankfully, that left a hole which ELT filled admirably at the turn of the century.

The title of your keynote speaker today, Professor of English Language Teaching, is clear evidence of how far we have come from those distant days, and how thankful we should be that a new generation of practical academics such as her and Dinali Fernando at Kelaniya, Chitra Jayatilleke and Madhubhashini Ratnayake at USJP and the lively lot at the Postgraduate Institute of English at the Open University are now making the running. I hope Sabaragamuwa under its current team will once again take its former place at the forefront of innovation.

To get back to your curriculum, I have been asked to teach for the paper on Advanced Reading and Writing in English. I worried about this at first since it is a very long time since I have taught, and I feel the old energy and enthusiasm are rapidly fading. But having seen the care with which the syllabus has been designed, I thought I should try to revive my flagging capabilities.

However, I have suggested that the university prescribe a textbook for this course since I think it is essential, if the rounded reading prescribed is to be done, that students should have ready access to a range of material. One of the reasons I began while at the British Council an intensive programme of publications was that students did not read round their texts. If a novel was prescribed, they read that novel and nothing more. If particular poems were prescribed, they read those poems and nothing more. This was especially damaging in the latter case since the more one read of any poet the more one understood what he was expressing.

Though given the short notice I could not prepare anything, I remembered a series of school textbooks I had been asked to prepare about 15 years ago by International Book House for what were termed international schools offering the local syllabus in the English medium. Obviously, the appalling textbooks produced by the Ministry of Education in those days for the rather primitive English syllabus were unsuitable for students with more advanced English. So, I put together more sophisticated readers which proved popular. I was heartened too by a very positive review of these by Dinali Fernando, now at Kelaniya, whose approach to students has always been both sympathetic and practical.

I hope then that, in addition to the texts from the book that I will discuss, students will read other texts in the book. In addition to poetry and fiction the book has texts on politics and history and law and international relations, about which one would hope postgraduate students would want some basic understanding.

Similarly, I do hope whoever teaches about Paradigms in English Education will prescribe a textbook so that students will understand more about what has been going on. Unfortunately, there has been little published about this but at least some students will I think benefit from my book on English and Education: In Search of Equity and Excellence? which Godage & Bros brought out in 2016. And then there was Lakmahal Justified: Taking English to the People, which came out in 2018, though that covers other topics too and only particular chapters will be relevant.

The former book is bulky but I believe it is entertaining as well. So, to conclude I will quote from it, to show what should not be done in Education and English. For instance, it is heartening that you are concerned with ‘social integration, co-existence and intercultural harmony’ and that you want to encourage ‘sensitivity towards different cultural and linguistic identities’. But for heaven’s sake do not do it as the NIE did several years ago in exaggerating differences. In those dark days, they produced textbooks which declared that ‘Muslims are better known as heavy eaters and have introduced many tasty dishes to the country. Watalappam and Buriani are some of these dishes. A distinguished feature of the Muslims is that they sit on the floor and eat food from a single plate to show their brotherhood. They eat string hoppers and hoppers for breakfast. They have rice and curry for lunch and dinner.’ The Sinhalese have ‘three hearty meals a day’ and ‘The ladies wear the saree with a difference and it is called the Kandyan saree’. Conversely, the Tamils ‘who live mainly in the northern and eastern provinces … speak the Tamil language with a heavy accent’ and ‘are a close-knit group with a heavy cultural background’’.

And for heaven’s sake do not train teachers by telling them that ‘Still the traditional ‘Transmission’ and the ‘Transaction’ roles are prevalent in the classroom. Due to the adverse standard of the school leavers, it has become necessary to develop the learning-teaching process. In the ‘Transmission’ role, the student is considered as someone who does not know anything and the teacher transmits knowledge to him or her. This inhibits the development of the student.

In the ‘Transaction’ role, the dialogue that the teacher starts with the students is the initial stage of this (whatever this might be). Thereafter, from the teacher to the class and from the class to the teacher, ideas flow and interaction between student-student too starts afterwards and turns into a dialogue. From known to unknown, simple to complex are initiated and for this to happen, the teacher starts questioning.’

And while avoiding such tedious jargon, please make sure their command of the language is better than to produce sentences such as these, or what was seen in an English text, again thankfully several years ago:

Read the story …

Hello! We are going to the zoo. “Do you like to join us” asked Sylvia. “Sorry, I can’t I’m going to the library now. Anyway, have a nice time” bye.

So Syliva went to the zoo with her parents. At the entrance her father bought tickets. First, they went to see the monkeys

She looked at a monkey. It made a funny face and started swinging Sylvia shouted: “He is swinging look now it is hanging from its tail its marvellous”

“Monkey usually do that’

I do hope your students will not hang from their tails as these monkeys do.

Midweek Review

Little known composers of classical super-hits

By Satyajith Andradi

Quite understandably, the world of classical music is dominated by the brand images of great composers. It is their compositions that we very often hear. Further, it is their life histories that we get to know. In fact, loads of information associated with great names starting with Beethoven, Bach and Mozart has become second nature to classical music aficionados. The classical music industry, comprising impresarios, music publishers, record companies, broadcasters, critics, and scholars, not to mention composers and performers, is largely responsible for this. However, it so happens that classical music lovers are from time to time pleasantly struck by the irresistible charm and beauty of classical pieces, the origins of which are little known, if not through and through obscure. Intriguingly, most of these musical gems happen to be classical super – hits. This article attempts to present some of these famous pieces and their little-known composers.

Pachelbel’s Canon in D

The highly popular piece known as Pachelbel’s Canon in D constitutes the first part of Johann Pachelbel’s ‘Canon and Gigue in D major for three violins and basso continuo’. The second part of the work, namely the gigue, is rarely performed. Pachelbel was a German organist and composer. He was born in Nuremburg in 1653, and was held in high esteem during his life time. He held many important musical posts including that of organist of the famed St Stephen’s Cathedral in Vienna. He was the teacher of Bach’s elder brother Johann Christoph. Bach held Pachelbel in high regard, and used his compositions as models during his formative years as a composer. Pachelbel died in Nuremburg in 1706.

Pachelbel’s Canon in D is an intricate piece of contrapuntal music. The melodic phrases played by one voice are strictly imitated by the other voices. Whilst the basso continuo constitutes a basso ostinato, the other three voices subject the original tune to tasteful variation. Although the canon was written for three violins and continuo, its immense popularity has resulted in the adoption of the piece to numerous other combinations of instruments. The music is intensely soothing and uplifting. Understandingly, it is widely played at joyous functions such as weddings.

Jeremiah Clarke’s Trumpet Voluntary

The hugely popular piece known as ‘Jeremiah Clarke’s Trumpet Voluntary’ appeared originally as ‘ The Prince of Denmark’s March’ in Jeremiah Clarke’s book ‘ Choice lessons for the Harpsichord and Spinet’, which was published in 1700 ( Michael Kennedy; Oxford Dictionary of Music ). Sometimes, it has also been erroneously attributed to England’s greatest composer Henry Purcell (1659 – 1695 ) and called ‘Purcell’s Trumpet Voluntary (Percy A. Scholes ; Oxford Companion to Music). This brilliant composition is often played at joyous occasions such as weddings and graduation ceremonies. Needless to say, it is a piece of processional music, par excellence. As its name suggests, it is probably best suited for solo trumpet and organ. However, it is often played for different combinations of instruments, with or without solo trumpet. It was composed by the English composer and organist Jeremiah Clarke.

Jeremiah Clarke was born in London in 1670. He was, like his elder contemporary Pachelbel, a musician of great repute during his time, and held important musical posts. He was the organist of London’s St. Paul’s Cathedral and the composer of the Theatre Royal. He died in London in 1707 due to self – inflicted gun – shot injuries, supposedly resulting from a failed love affair.

Albinoni’s Adagio

The full title of the hugely famous piece known as ‘Albinoni’s Adagio’ is ‘Adagio for organ and strings in G minor’. However, due to its enormous popularity, the piece has been arranged for numerous combinations of instruments. It is also rendered as an organ solo. The composition, which epitomizes pathos, is structured as a chaconne with a brooding bass, which reminds of the inevitability and ever presence of death. Nonetheless, there is no trace of despondency in this ethereal music. On the contrary, its intense euphony transcends the feeling of death and calms the soul. The composition has been attributed to the Italian composer Tomaso Albinoni (1671 – 1750), who was a contemporary of Bach and Handel. However, the authorship of the work is shrouded in mystery. Michael Kennedy notes: “The popular Adagio for organ and strings in G minor owes very little to Albinoni, having been constructed from a MS fragment by the twentieth century Italian musicologist Remo Giazotto, whose copyright it is” (Michael Kennedy; Oxford Dictionary of Music).

Boccherini’s Minuet

The classical super-hit known as ‘Boccherini’s Minuet’ is quite different from ‘Albinoni’s Adagio’. It is a short piece of absolutely delightful music. It was composed by the Italian cellist and composer Luigi Boccherini. It belongs to his string quintet in E major, Op. 13, No. 5. However, due to its immense popularity, the minuet is performed on different combinations of instruments.

Boccherini was born in Lucca in 1743. He was a contemporary of Haydn and Mozart, and an elder contemporary of Beethoven. He was a prolific composer. His music shows considerable affinity to that of Haydn. He lived in Madrid for a considerable part of his life, and was attached to the royal court of Spain as a chamber composer. Boccherini died in poverty in Madrid in 1805.

Like numerous other souls, I have found immense joy by listening to popular classical pieces like Pachelbel’s Canon in D, Jeremiah Clarke’s Trumpet Voluntary, Albinoni’s Adagio and Boccherini’s Minuet. They have often helped me to unwind and get over the stresses of daily life. Intriguingly, such music has also made me wonder how our world would have been if the likes of Bach, Handel, Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, and Schubert had never lived. Surely, the world would have been immeasurably poorer without them. However, in all probability, we would have still had Pachelbel’s Canon in D, Jeremiah Clarke’s Trumpet Voluntary, Albinoni’s Adagio, and Boccherini’s Minuet, to cheer us up and uplift our spirits.

Midweek Review

The Tax Payer and the Tough

By Lynn Ockersz

The tax owed by him to Caesar,

Leaves our retiree aghast…

How is he to foot this bill,

With the few rupees,

He has scraped together over the months,

In a shrinking savings account,

While the fires in his crumbling hearth,

Come to a sputtering halt?

But in the suave villa next door,

Stands a hulk in shiny black and white,

Over a Member of the August House,

Keeping an eagle eye,

Lest the Rep of great renown,

Be besieged by petitioners,

Crying out for respite,

From worries in a hand-to-mouth life,

But this thought our retiree horrifies:

Aren’t his hard-earned rupees,

Merely fattening Caesar and his cohorts?