Sat Mag

‘Integrity, professionalism and empathy, the ethos of officering’

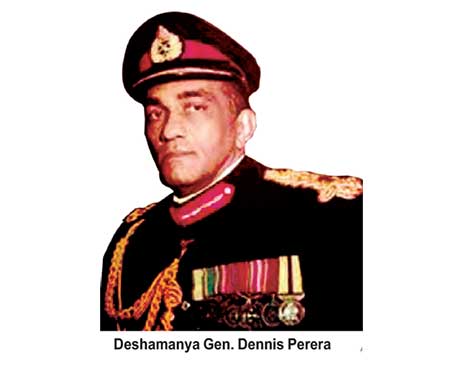

(The seventh death anniversary of Deshamanya Gen. Dennis Perera fell on 11 August. This is the Dennis Perera memorial oration 2016 delivered by Air Chief Marshal Gagan Bulathsinghala RWP, RSP, VSV, USP, Mphil, Msc, FIM(SL)ndc, psc, Former Commander of the Air Force and Ambassador to Afghanistan)

The former US President and Supreme Commander Allied Expeditionary Forces in WW 2, Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower states:

“The supreme quality for leadership is unquestionable INTEGRITY.

Without it, no real success is possible;

No matter whether it is on a section, gang, a football field,

In an army or in an office!”

Reflecting on the illustrious career of the late Deshamanya Gen. Dennis Perera, one sees an outstanding leader whose lifetime principle was integrity of the highest order personifying exemplary moral courage to do what is needed and what is right, while being an officer and gentleman, par-excellence.

The young Master Dennis Perera was educated at St. Peter’s College, Colombo, and excelled as a multifaceted student both in academics and sport. In 1949, at the age of 19, he answered the call to the profession of arms to join the then young Ceylon Army.

Young Master Dennis Perera’s mother’s dream was for her son to a join the order and become a Priest, due to her strong faith in religion. However, an uncle of Master Perera, who was in the Ceylon Police, saw him more as soldier material and convinced his parents to let him join the Ceylon Army.

General Perera received his initial military training at Mons Officer Cadet School, UK, and the Royal Military Academy Sandhurst. He was also a graduate of the British Army’s Staff College, Camberley. In 1977, at the age of 46, he was bestowed the twin honours of being the first Engineer officer and also the youngest officer ever to be made the Commander of the Sri Lanka Army. Further the late Gen Perera was an alumni of the prestigious National Defence Collage of India.

On retirement, Gen. Perera continued to serve the nation and the corporate sector, first as the High Commissioner to Australia, and later as Chairman of the Securities Exchange Commission, and as Chairman of Ceylon Tobacco Company, and two other high performing Companies. In the year 2000, acknowledging his meritorious service to the nation he was bestowed the title, ‘Deshamanya’. He was next elevated to a Four Star General, in the year 2000.

Gen. Perera possessed a unique character and was known for his compassion and inspiration towards the people around him. He was well known to be a shrewd strategist and a sound leader who always lived up to the motto of the Royal Military Academy Sandhurst, ‘Serve to Lead’. Gen Perera maintained the highest level of integrity as an Officer and remains a role model for officering in the armed forces of Sri Lanka. As an officer, and a statesman, he made an everlasting impression for the military fraternity and the nation.

In 2010, I had an interesting experience when I flew with Gen. Perera and his gracious Lady to attend the golden Jubilee celebrations of the National Defence College, New Delhi. Though he had hung up his uniform, some time back, I felt the he remained a hard core General, the way he expressed his thoughts on military traditions. Every conversation, I had with Gen. Perera, made me feel proud as a military officer. It was very apparent that he was most upright and proud of the profession of arms. He professed that a military officer should never lean against any one or be a shadow to any one, and must stand up firm for what is right.

I am very confident that this august audience needs no elaboration on Gen. Perera‘s role in establishing the KDU. Gen. Perera pioneered and triggered the conversion of the ‘Kandawala Estate’ into the esteemed Military University it is today.

It was indeed fitting that Gen. Perera himself was appointed the first Chancellor after it became a University. Gen. Dennis Perera’s visionary leadership and foresight provided our Army with the Commandos and the Women’s Corps as integral units, in corporate parlance two timely investments that have brought rich dividends.

The Association of Retired Flag Rank Officers (ARFRO), which has brought us together this evening, was another successful effort of Gen Dennis Perera. This is the professional institution of the profession of arms in Sri Lanka. It is a member of the esteemed Organization of Professional Associations of Sri Lanka and is affiliation to the World Consultative Association of Retired Generals, Admirals & Air Marshals. A truly worthy outfit to be in, for military veteran of Flag rank after a retirement.

Ladies and gentlemen, Gen. Dennis Perera, was a passionate leader, a visionary and a professional, whose life is worthy of celebration at the highest level of esteem and appreciation.

Considering the epitome of military officering in Sri Lanka whom this oration is dedicated to, I chose as my discourse the obvious attributes practiced by him.

General Collin Powell, the former US Secretary of State said:

“The most important thing I learned is that soldiers watch what their leaders do. You can give them classes and lecture them forever, but it is your personal example they will follow.”

Ladies and gentlemen, from the very beginning of civilization, when mankind engaged in war fighting, the officer was the nucleus and the pivot around which the rank and file rallied for guidance, direction and leadership. Thus, an officer with firm, coherent decisional ability and robust leadership becomes important for the structural integrity of any military unit.

The contemporary armed forces are ramping up their efforts to groom a capable breed of officers to lead and confront the asymmetric threats encountered by nations in battle spaces which are not clearly defined. It is the need of the day that this effort should persist from the moment an officer joins, as it is only knowledge and its continuous application that will make one perfect.

In this context I would like to quote from Aristotle

“We are what we repeatedly do; Excellence, therefore, is not an act but a habit“.

For any military officer, Integrity is the primary attribute which strengthens his moral fiber to control emotions, both in times of adversity and success. Integrity is a leadership attribute discussed at length in our profession.

Integrity is defined as, ‘The quality of truthfulness, honesty and maintaining of moral standard’.

Integrity then should not be considered a mere attribute, but a virtue to live by for any officer.

The world today discusses and studiously studies “Ethics” in all spheres public, corporate, national and international. Similarly the military today has been rediscovered around an ethical compass, thus military leaders need to be aware of the dramatic lift in the bar of standards in accountability, honesty, and trust.

An officer is entrusted with; state secrets relating integrity of a nation and the lives of the public and the men he leads. If an officer is found to be dishonest or disloyal, it means that his character has two sides and one will manifest to suit the circumstance, to meet his personal liking and not the common goal.

The officers as leaders must demonstrate the moral fiber to be selfless to address the needs of their subordinates before their own, and possess the integrity to seek wholesome solutions.

Our great nation expects complete honesty and integrity from us; upon which it has entrusted its security and integrity and given us all which have said we needed to do the job. Anything less, if delivered will ultimately put our nation at risk by sabotaging its future, and its strategy to compete in the world. Therefore General Eisenhower’s’ edict that “Integrity is the supreme quality of leadership” is underscored with no doubt.

Even though midway, I need to make a disclaimer that I will generalize in relation to gender and refer to military personnel as HE or HIM, only to make life easier for me in this discourse and in no way lessen the immense contribution of the ladies in our profession. Professionalism is the next attribute of officering that I endeavor to relate to.

General Charles De Gaulle (Galle), the decorated French Soldier and President describes the men of our profession as:

“Men who adopt the profession of arms submit to their own free will to a law of perpetual constraint of their own accord.

If they drop in their tracks, if their ashes are scattered in the four winds that is all part and parcel of their job.”

The contemporary military culture is far distanced from the traditional forms of war fighting, as cyber space, smart equipment and proactive tactics have encroached at a rapid pace.

However, technology cannot and will not replace the concept of professional officering. Thus the military needs a corps of highly skilled technology savvy officers to command them in tomorrow’s uncertain environment.

On the other hand, the knowledge of common affairs and skill that is expected from an officer cannot be obtained only by referring to a stack of books and manuals only. It is cumulative, and gained through hard experiences learnt through failures and the continuous attempts to succeed.

The men, the officer of today is called upon to command, are technology savvy, well educated, well socialized and have grown up in a free thinking environment. To be able command their respect and followership one needs to prove professional ability beyond doubt.

The opponents of peace the officer of today will be called upon to confront, are shrewd exponents of asymmetric warfare and are capable of exceptional cruelty and violence as well as, well strategized operations. They have learned and trained to exploit technology and the human mind, with much precision and process to achieve their sick ideological objectives.

Their standard modus operandi is to attack the social fabric at the same time from many directions.

In this context it is imperative for the officer who leads from the front to develop knowledge and all round capacity that includes ‘outside ones lane’ knowledge.

Ladies and gentlemen, at the end of the day, the most important and cardinal characteristic a professional needs to have is the knowledge and competence in one’s own field.

The legendary Field Marshal Sam Manekshaw, of the Indian army has once said:

“….. you cannot be born with professional knowledge and professional competence even if you are a child of Prime Minister, or the son of an industrialist or the progeny of a Field Marshal. Professional knowledge and professional competence have to be acquired by hard work and constant study.”

In addition to the explicit and tacit knowledge an officer is armed with, he also needs to have an inner thirst and passion for knowledge for things unknown and things outside the zone of comfort. For this the officer needs to be enthusiastic in the never ending process of developing new skills and acquiring new knowledge.

Due to the uncertainty, the high stress levels, and the continuously evolving threats to the society he serves, an officer’s professional competence must be at the highest level at all times.

For this it is necessary, that the appropriate candidates only be selected to hold the commission, and the aspects of their selection, training, assigning and evaluation, given the highest precedence of priority by the authorities concerned. Incompetent and unprofessional officers, who are unsuitable to lead men and incapable of rational decision-making, should not be tolerated in any military institution.

The popular edict goes on to say that “there are no bad soldiers but only bad officers”

Professionalism for an officer is not only knowing the job, but it also relates to the discipline and decorum that he and his men maintain while engaged on the task, whatever the circumstances may be. This goes beyond an officer inspecting haircuts, and turn out and bearing but reaches out to greater depth of intervening into unprofessional conduct, such as human rights abuses, or even fraternization. Both these occur due to the lack of self-control and the moral fiber to control ones emotions and is a failure that should be purged from the professional officer corps at the first hint of existence.

In this context, it is the conduct of the officer that the men will follow, and this will then decide, the esteem of the unit in the social domain it operates.

As per the Sri Lanka Air Force Ethos, Core Values and Standards adopted from the Royal Air Force, it applies the following test to determine the code of social conduct.

‘Have the actions or behaviour of an individual adversely impacted, or are they likely to impact, on the efficiency or operational effectiveness of the Sri Lanka Air Force?’

This test applies to all individuals of the SLAF, on or off duty, in order to undermine unprofessional behaviour without hesitation. As far as the social fabric surrounding the Sri Lankan military is concerned.

I strongly believe that this ‘self-query’ can be applied to any service institution. In the Sri Lankan post conflict environment, where we experience numerous cynical and false expressions, relating to our past and present conduct, it is the leadership that must emerge with professionalism. For this the cornerstone of professionalism must be invented upon good order, discipline, decorum, and exemplary conduct. If our profession loses the trust and confidence of the societal domain, due to unprofessional conduct, it becomes increasingly difficult to acquire the much needed popular support for the conduct of our core competency. Therefore, we must bear in mind that we as officers are responsible for the public’s perception of our institutions.

From professionalism I now delve into Empathy, the softer and lesser discussed attribute in an officer’s repertoire.

General Omar Bradley better known as the soldiers general during WW2 in one of his papers on Leadership states;

“A leader should possess human understanding and consideration for others. Men are not robots and should not be treated as though they were machines. I do not by any means suggest coddling. But men are highly intelligent, complicated beings who will respond favourably to human understanding and consideration. By this means, their leader will get maximum effort from each of them.”

Knowing your men and to possess the ability to understand and share their feelings are essential empathetic traits of a leader. It is important to develop a memory for names and faces of the people under ones command. The saying goes, ‘a man’s name is to him the most important word in his language’. Our subordinates endure great pains emotionally, psychologically, physically and socially during war and during peace.

For an officer to mitigate the emotional pain, the officer needs to be able to empathize and make the man feel that his pain is felt even though not necessarily shared or the issue resolved. The approach to resolving subordinates emotional issues is often confounding as only the manifestation is seen.

Human and social issues faced by our subordinates cannot be resolved by the mere application of military law or generous distribution of welfare items to families of subordinates. The genuine caring nature and the ability to feel subordinates pain and see their point of view even though not necessarily accepted are the qualities of an empathetic leader.

Thus, empathy, is an integral part of officering as our subordinates, are constantly exposed to multifarious and intense stressors.

If we carefully review history we see the empathetic side of leaders who were ruthless in the execution of war.

Field Marshall Erwin Rommell the legendry ‘Dessert Fox’ of the Africa Korps, is known to have been greatly loved by his men and respected by the enemy; he is said to have looked after his men well and grieved at their loss, It is also said that he ignored orders from Nazi leadership to summarily execute prisoners of war.

When an officer is aware of the emotional state of his men, it creates an unspoken bond of trust between them and the officer. Without empathy and compassion ones subordinates will always keep their ‘guards up’ and be cautious and will have less camaraderie towards their leader.

General George S. Patton, better known by men as “ole blood an guts” is quoted in the book “War as I knew it”

“Officers are responsible, not only for the conduct of their men in battle, but also for their health and contentment when not fighting. An officer must be the last man to take shelter from fire, and the first to move forward.

Throughout my discourse I have elaborated on three core attributes that are the Ethos of Officering, Integrity, Professionalism, and Empathy. The thresholds of these three attributes converge in most instances supporting one and other.

These three attributes taken in broader sense encompass all values that we would like a leader of our choice to possess. It is not rationally possible for a single human being to possess all three values in their entirety, but we as seniors need to emphasize the importance of these attributes to our younger generations.

As I said, our younger generations have grown up in a “free thinking environment” and tend to refer to the words realism and pragmatism instead of values. It is in this sense that we need to create awareness of the importance of “means as well as the successful achievement of the end” It is here that the Ethos of officering comes into bearing.

In the SLAF we have recently introduced the booklet “ETHOS & CORE VALUES” in this we have translated our values into a broad statement.Through this statement our intention is to give the officer an identity based on value and say ‘this is who I am’. At this point I must acknowledge that this book is based on an inheritance from The Royal Air Force but has been remodeled to suit our needs, our culture, and our own values.

The art of officering has evolved in many ways to suit the trends of change, but there are many unwritten laws, traditions, customs, and a value based system of officering handed down by our forefathers of this profession that our generation will now hand over to the next. Men and technology will come and retire but these value based traditions cannot be changed nor should review be attempted, as they stem from valuable lessons learnt from engagement in painful conflict.

Integrity, professionalism and empathy are the attributes that serve as the pillars of genuine officering, they need to be taught, nurtured, developed and appreciated when practiced. This will ensure that the respect and esteem of our sacred profession will remain intact.

May the Late Deshamanya Gen. Dennis Perera be remembered by the future generation for his excellence in soldiering!

- News Advertiesment

See Kapruka’s top selling online shopping categories such as Toys, Grocery, Flowers, Birthday Cakes, Fruits, Chocolates, Clothing and Electronics. Also see Kapruka’s unique online services such as Money Remittence,News, Courier/Delivery, Food Delivery and over 700 top brands. Also get products from Amazon & Ebay via Kapruka Gloabal Shop into Sri Lanka.

Sat Mag

End of Fukuyama’s last man, and triumph of nationalism

By Uditha Devapriya

What, I wonder, are we to make of nationalism, the most powerful political force we have today? Liberals dream on about its inevitable demise, rehashing a line they’ve been touting since goodness-knows-when. Neoliberals do the same, except their predictions of its demise have less to do with the utopian triumph of universal values than with their undying belief in the disappearance of borders and the interlinking of countries and cities through the gospel of trade. Both are wrong, and grossly so. There is no such thing as a universal value, and even those described as such tend to differ in time and place. There is such a thing as trade, and globalisation has made borders meaningless. But far from making nationalism meaningless, trade and globalisation have in fact bolstered its relevance.

The liberals of the 1990s were (dead) wrong when they foretold the end of history. That is why Francis Fukuyama’s essay reads so much like a wayward prophet’s dream today. And yet, those who quote Fukuyama tend to focus on his millenarian vision of liberal democracy, with its impending triumph across both East and West. This is not all there is to it.

To me what’s interesting about the essay isn’t his thesis about the end of history – whatever that meant – but what, or who, heralds it: Fukuyama’s much ignored “last man.” If we are to talk about how nationalism triumphed over liberal democracy, how populists trumped the end of history, we must talk about this last man, and why he’s so important.

In Fukuyama’s reading of the future, mankind gets together and achieves a state of perfect harmony. Only liberal democracy can galvanise humanity to aspire to and achieve this state, because only liberal democracy can provide everyone enough of a slice of the pie to keep us and them – majority and minority – happy. This is a bourgeois view of humanity, and indeed no less a figure than Marx observed that for the bourgeoisie, the purest political system was the bourgeois republic. In this purest of political systems, this bourgeois republic, Fukuyama sees no necessity for further progression: with freedom of speech, the right to assemble and dissent, an independent judiciary, and separation of powers, human beings get to resolve, if not troubleshoot, all their problems. Consensus, not competition, becomes the order of the day. There can be no forward march; only a turning back.

Yet that future state of affairs suffers from certain convulsions. History is a series of episodic progressions, each aiming at something better and more ideal. If liberal democracy, with its championing of the individual and the free market, triumphs in the end, it must be preceded by the erosion of community life. The problem here is that like all species, humanity tends to congregate, to gather as collectives, as communities.

“[I]n the future,” Fukuyama writes, “we risk becoming secure and self-absorbed last men, devoid of thymotic striving for higher goals in our pursuit of private comforts.” Being secure and self-absorbed, we become trapped in a state of stasis; we think we’re in a Panglossian best of all possible worlds, as though there’s nothing more to achieve.

Fukuyama calls this “megalothymia”, or “the desire to be recognised as greater than other people.” Since human beings think in terms of being better than the rest, the fact of reaching a point where we don’t need to show we’re better lulls us to a sense of restless dissatisfaction. The inevitable follows: some of us try finding out ways of doing something that’ll put us a cut above the rest. In the rush to the top, we end up in “a struggle for recognition.”

Thus the last men of history, in their quest to find some way they can show that they’re superior, run the risk of becoming the first men of history: rampaging, irrational hordes, hell-bent on fighting enemies, at home and abroad, real and imagined.

Fukuyama tries to downplay this risk, contending that liberal democracy provides the best antidote against a return to such a primitive state of nature. And yet even in this purest of political systems, security becomes a priority: to prevent a return to savagery, there must be an adequate deterrent against it. In his scheme of things, two factors prevent history from realising the ideals of humanity, and it is these that make such a deterrent vital: persistent war and persistent inequality. Liberal democracy does not resolve these to the extent of making them irrelevant. Like dregs in a teacup, they refuse to dissolve.

Fukuyama tries to downplay this risk, contending that liberal democracy provides the best antidote against a return to such a primitive state of nature. And yet even in this purest of political systems, security becomes a priority: to prevent a return to savagery, there must be an adequate deterrent against it. In his scheme of things, two factors prevent history from realising the ideals of humanity, and it is these that make such a deterrent vital: persistent war and persistent inequality. Liberal democracy does not resolve these to the extent of making them irrelevant. Like dregs in a teacup, they refuse to dissolve.

The problem with those who envisioned this end of history was that they conflated it with the triumph of liberal democracy. Fukuyama committed the same error, but most of those who point at his thesis miss out on the all too important last part of his message: that built into the very foundation of liberal democracy are the landmines that can, and will, blow it off. Yet this does not erase the first part of his message: that despite its failings, it can still render other political forms irrelevant, simply because, in his view, there is no alternative to free markets, constitutional republicanism, and the universal tenets of liberalism. There may be such a thing as civilisation, and it may well divide humanity. Such niceties, however, will sooner or later give way to the promise of globalisation and free trade.

It is no coincidence that the latter terms belong in the dictionary of neoliberal economists, since, as Kanishka Goonewardena has put it pithily, no one rejoiced at Fukuyama’s vision of the future of liberal democracy more than free market theorists. But could one have blamed them for thinking that competitive markets would coexist with a political system supposedly built on cooperation? To rephrase the question: could one have foreseen that in less than a decade of untrammelled deregulation, privatisation, and the like, the old forces of ethnicity and religious fundamentalism would return? Between the Berlin Wall and Srebrenica, barely three years had passed. How had the prophets of liberalism got it so wrong?

Liberalism traces its origins to the mid-19th century. It had the defect of being younger, much younger, than the forces of nationalism it had to fight and put up with. Fast-forward to the end of the 20th century, the breakup of the Soviet Union, and the shift in world order from bipolarity to multipolarity, and you had these two foes fighting each other again, only this time with the apologists of free markets to boot. This three-way encounter or Mexican standoff – between the nationalists, the liberal democrats, and the neoliberals – did not end up in favour of dyed-in-the-wool liberal democrats. Instead it ended up vindicating both the nationalists and the neoliberals. Why it did so must be examined here.

The fundamental issue with liberalism, which nationalism does not suffer from, is that it views humanity as one. Yet humanity is not one: man is man, but he is also rich, poor, more privileged, and less privileged. Even so, liberal ideals such as the rule of law, separation of powers, and judicial independence tend to believe in the equality of citizens.

So long as this assumption is limited to political theory, nothing wrong can come out of believing it. The problem starts when such theories are applied as economic doctrines. When judges rule in favour of welfare cuts or in favour of corporations over economically backward communities, for instance, the ideals of humanity no longer appear as universal as they once were; they appear more like William Blake’s “one law for the lion and ox.”

That disjuncture didn’t trouble the founders of European liberalism, be it Locke, Rousseau, or Montesquieu, because for all their rhetoric of individual freedoms and liberties they never pretended to be writing for anyone other than the bourgeoisie of their time. Indeed, John Stuart Mill, beloved by advocates of free markets in Sri Lanka today, bluntly observed that his theories did not apply to slaves or subjects of the colonies. To the extent that liberalism remained cut off from the “great unwashed” of humanity, then, it could thrive because it did not face the problem of reconciling different classes into one category. Put simply, humanity for 19th century liberals looked white, bourgeois, and European.

The tail-end of the 20th century could not have been more different to this state of affairs. I will not go into why so and how come, but I will say that between the liberal promise of all humanity merging as one, the nationalist dogma of everyone pitting against everyone else, and the neoliberal paradigm of competition and winner-takes-all, the winner could certainly not be ideologues who believed in the withering away of cultural differences and the coming together of humanity. As the century drew to a close, it became increasingly obvious that the winners would be the free market and the nationalist State. How exactly?

Here I like to propose an alternative reading of not just Fukuyama’s end of history and last man, but also the triumph of nationalism and neoliberalism over liberal democracy. In 1992 Benjamin Barber wrote an interesting if not controversial essay titled “Jihad vs. McWorld” to The Atlantic in which he argued that two principles governed the post-Cold War order, and of the two, narrow nationalism threatened globalisation. Andre Gunder Frank wrote a reply to Barber where he contended that, far from opposing one another, narrow nationalism, or tribalism, in fact resembled the forces of globalisation – free markets and free trade – in how they promoted the transfer of resources from the many to the few.

For Gunder Frank, the type of liberal democracy Barber championed remained limited to a narrow class, far too small to be inclusive and participatory. In that sense “McWorldisation”, or the spread of multinational capital to the most far-flung corners of the planet, would not lead to the disappearance of communal or cultural fragmentation, but would rather bolster and lay the groundwork for such fragmentation. Having polarised entire societies, especially those of the Global South, along class lines, McWorldisation becomes a breeding ground for the very “axial principle” Barber saw as its opposite: “Jihadism.”

Substitute neoliberalism for McWorldisation, nationalism for Jihadism, and you see how the triumph of one has not led to the defeat of the other. Ergo, my point: nationalism continues to thrive, not just because (as is conventionally assumed) liberal democracy vis-à-vis Francis Fukuyama failed, but more importantly because, in its own way, neoliberalism facilitated it. Be it Jihadism there or Jathika Chintanaya here, in the Third World of the 21st century, what should otherwise have been a contradiction between two forces opposed to each other has instead become a union of two opposites. Hegel’s thesis and antithesis have hence become a grand franken-synthesis, one which will govern the politics of this century for as long as neoliberalism survives, and for as long as nationalism thrives on it.

The writer can be reached at udakdev1@gmail.com

Sat Mag

Chitrasena: Traditional dance legacy perseveres

By Rochelle Palipane Gunaratne

Where would Mother Lanka’s indigenous dance forms be, if not for the renaissance of traditional dance in the early 1940s? January 26, 2021 marked the 100th birth anniversary of the legendary Guru Chitrasena who played a pivotal role in reviving a dance form which was lying dormant, ushering in a brand new epoch to a traditional rhythmic movement that held sway for over two millennia.

“There was always an aura that drew us all to Seeya and we were mesmerized by it,” enthused Heshma, Artistic Director of the Chitrasena Dance Company and eldest grand-daughter of the doyen of dance. She reminisced about her legendary grandfather during a brief respite from working on a video depicting his devotion to a dance form that chose him.

“Most classical art forms require a lifetime of learning and dedication as it’s also a discipline which builds character and that is what we have been inculcated with by Guru Chitrasena, who also left us with an invaluable legacy,” emphasized Heshma, adding that it makes everything else pale in comparison and provides the momentum even when faced with trials.

Blazing a dynamic trail

The patriarch’s life and times resonated with an era of change in Ceylon, here was an island nation that was almost overshadowed by a gigantic peninsula whose influence had been colossal. Being colonized by the western empires meant a further suppression for over four centuries. Yet, hidden in the island’s folds were artistes, dancers and others who held on almost devoutly to their sacred doctrines. The time was ripe for the harvest and the need for change was almost palpable. To this era was born Chitrasena, who took the idea by its horns and led it all the way to the world stage.

The patriarch’s life and times resonated with an era of change in Ceylon, here was an island nation that was almost overshadowed by a gigantic peninsula whose influence had been colossal. Being colonized by the western empires meant a further suppression for over four centuries. Yet, hidden in the island’s folds were artistes, dancers and others who held on almost devoutly to their sacred doctrines. The time was ripe for the harvest and the need for change was almost palpable. To this era was born Chitrasena, who took the idea by its horns and led it all the way to the world stage.

He literally coaxed the hidden treasures of the island out of the Gurus of old whose birthrights were the traditional dance forms, who did not have a need or a desire for the stage. Their repertoire was relegated to village ceremonies, peraheras and ritual sacrifices. The nobles, at the time, entertained themselves sometimes watching these ‘devil dancers.’ In fact, some of these traditional dancers are said to have been taken as part of a ‘human circus’ act to be presented abroad in the late 1800s.

But how did Chitrasena change that thinking? He went in search of these traditional Gurus, lived with them, learned the traditions and then re-presented them as a respectable dance art on the stage. He revolutionized the manner in which we, colonized islanders, viewed what was endemic to us, suffice it to say he gave it the pride and honour it deserved, though it came with a supreme sacrifice, a lifetime of commitment to dancing, braving the criticism and other challenges that were constantly put up to deter him. Not only did he commit himself to this colossal task but the involvement of his immediate family and the family of dancers was exceptional, bordering on devotion as their lives revolved around dance alone.

Imbued in them is the desire to dance and share their knowledge with others and it is done through various means, such as giving prominence to Gurus of yore, hence the Guru Gedara Festival which saw the confluence of many artistes and connoisseurs who mingled at the Chitrasena Kalayathanaya in August 2018. Moreover the family has been heavily involved in inculcating a love for dancing in all age groups through various dance classes for over 75 years, specifically curated dance workshops, concerts and scholarships for students who are passionate about dancing.

While hardship is what strengthens our inner selves, there were questions posed by Chitrasena that we need to ask ourselves and the authorities concerning the arts and their development in our land. “Yes, there is a burgeoning interest in expanding infrastructure in many different fields as part of post war development. But what purpose will it serve if there are no artistes to perform in all the new theatres to be built for instance?” queries Heshma. The new theatres we have now are not even affordable to most of the local artistes. “When I refer to dance I am not referring to the cabaret versions of our traditional forms. I am talking about the dancers who want to immerse themselves in a manner that refuses to compromise their art for any reason at all, not to cater to the whims and fancies of popular trends, vulgarization for financial gain or simply diluting these sacred art forms to appeal to audiences who are ignorant about its value,” she concludes. There are still a few master artistes and some very talented young artistes, who care very deeply about our indigenous art forms, who need to be encouraged and supported to pursue their passion, which then will help preserve our rich cultural heritage. But the support for the arts is so minimal in our country that one wonders as to how their astute devotion will prevail in this unhinged world where instant fixes run rampant.

While hardship is what strengthens our inner selves, there were questions posed by Chitrasena that we need to ask ourselves and the authorities concerning the arts and their development in our land. “Yes, there is a burgeoning interest in expanding infrastructure in many different fields as part of post war development. But what purpose will it serve if there are no artistes to perform in all the new theatres to be built for instance?” queries Heshma. The new theatres we have now are not even affordable to most of the local artistes. “When I refer to dance I am not referring to the cabaret versions of our traditional forms. I am talking about the dancers who want to immerse themselves in a manner that refuses to compromise their art for any reason at all, not to cater to the whims and fancies of popular trends, vulgarization for financial gain or simply diluting these sacred art forms to appeal to audiences who are ignorant about its value,” she concludes. There are still a few master artistes and some very talented young artistes, who care very deeply about our indigenous art forms, who need to be encouraged and supported to pursue their passion, which then will help preserve our rich cultural heritage. But the support for the arts is so minimal in our country that one wonders as to how their astute devotion will prevail in this unhinged world where instant fixes run rampant.

Yet, the cry of the torchbearers of unpretentious traditional dance theatre in our land, is to provide it a respectable platform and the support it rightly deserves, and this is an important moment in time to ensure the survival of our dance. With this thought, one needs to pay homage to Chitrasena whose influence transcends cultures and metaphorical boundaries and binds the connoisseurs of dance and other art forms, leaving an indelible mark through the ages.

Amaratunga Arachchige Maurice Dias alias Chitrasena was born on 26 January 1921 at Waragoda, Kelaniya, in Sri Lanka. Simultaneously, in India, Tagore had established his academy, Santiniketan and his lectures on his visit to Sri Lanka in 1934 had inspired a revolutionary change in the outlook of many educated men and women. Tagore had stressed the need for a people to discover its own culture to be able to assimilate fruitfully the best of other cultures. Chitrasena was a schoolboy at the time, and his father Seebert Dias’ house had become a veritable cultural confluence frequented by the literary and artistic intelligentsia of the time.

In 1936, Chitrasena made his debut at the Regal Theatre at the age of 15 in the role of Siri Sangabo, the seeds of the first Sinhala ballet produced and directed by his father. Presented in Kandyan style, Chitrasena played the lead role, and this created a stir among the aficionados who noticed the boy’s talents. D.B. Jayatilake, who was Vice-Chairman of the Board of Ministers under the British Council Administration, Buddhist scholar, Founder and first President of the Colombo Y.M.B.A, freedom fighter, Leader of the State Council and Minister of Home Affairs, was a great source of encouragement to the young dancer.

In 1936, Chitrasena made his debut at the Regal Theatre at the age of 15 in the role of Siri Sangabo, the seeds of the first Sinhala ballet produced and directed by his father. Presented in Kandyan style, Chitrasena played the lead role, and this created a stir among the aficionados who noticed the boy’s talents. D.B. Jayatilake, who was Vice-Chairman of the Board of Ministers under the British Council Administration, Buddhist scholar, Founder and first President of the Colombo Y.M.B.A, freedom fighter, Leader of the State Council and Minister of Home Affairs, was a great source of encouragement to the young dancer.

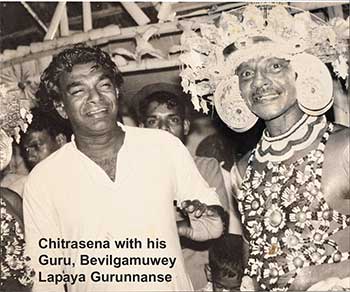

Chitrasena learnt the Kandyan dance from Algama Kiriganitha Gurunnanse, Muddanawe Appuwa Gurunnanse and Bevilgamuwe Lapaya Gurunnanse. Having mastered the traditional Kandyan dance, his ‘Ves Bandeema’, ceremony of graduation by placing the ‘Ves Thattuwa’ on the initiate’s head, followed by the ‘Kala-eliya’ mangallaya, took place in 1940. In the same year he proceeded to Travancore to study Kathakali dance at Sri Chitrodaya Natyakalalayam under Sri Gopinath, Court dancer in Travancore. He gave a command performance with Chandralekha (wife of portrait painter J.D.A. Perera) before the Maharaja and Maharani of Travancore at the Kowdiar Palace. He later studied Kathakali at the Kerala Kalamandalam.

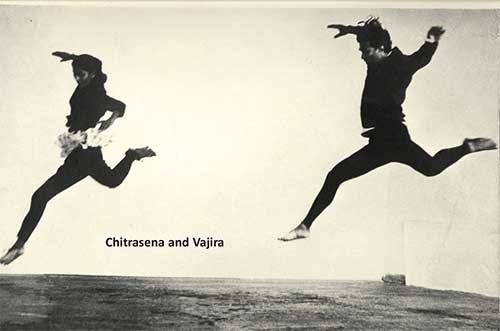

In 1941, Chitrasena performed at the Regal Theatre, one of the first dance recitals of its kind, before the Governor Sir Andrew Caldecott and Lady Caldecott with Chandralekha and her troupe. Chandralekha was one of the first women to break into the field of the Kandyan dance, followed by Chitrasenás protégé and soul mate, Vajira, who then became the first professional female dancer. Thereafter, Chitrasena and Vajira continued to captivate audiences worldwide with their dynamic performances which later included their children, Upeka, Anjalika and students. The matriarch, Vajira took on the reigns at a time when the duo was forced to physically separate with the loss of the house in Colpetty where they lived and worked for over 40 years. Daughter Upeka then continued to uphold the tradition, leading the dance company to all corners of the globe during a very difficult time in the country. At present, the grand-children Heshma, Umadanthi and Thaji interweave their unique talents and strengths to the legacy inspired by Guru Chitrasena.

Sat Mag

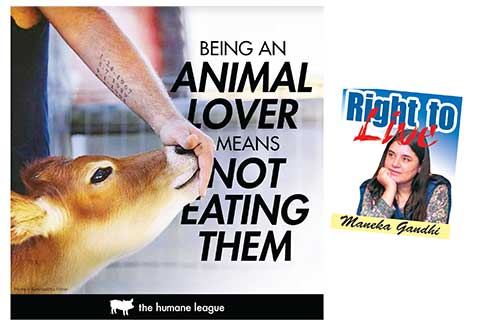

Meat by any other name is animal flesh

In India most animal welfare people are vegetarians. We, in People for Animals, insist on that. After all, you cannot want to look after animals and then eat them. But most meat eaters, whether they are animal people or not, have a hesitant relationship with the idea of killing animals for food. They enjoy the taste of meat, but shy away from making the connection that animals have been harmed grievously in the process.

This moral conflict is referred to, in psychological terms, as the ‘meat paradox’. A meat eater will eat caviar, but he will refuse to listen to someone telling him that this has been made from eggs gotten from slitting the stomach of a live pregnant fish. The carnivorous individual simply does not want to feel responsible for his actions. Meat eaters and sellers try and resolve this dilemma by adopting the strategy of mentally dissociating meat from its animal origins. For instance, ever since hordes of young people have started shunning meat, the meat companies and their allies in the government, and nutraceutical industry, have deliberately switched to calling it “protein”. This is an interesting manipulation of words and a last-ditch attempt to influence consumer behaviour.

For centuries meat has been a part of people’s diet in many cultures. Global meat eating rose hugely in the 20th century, caused by urbanization and developments in meat production technology. And, most importantly, the strategies used by the meat industry to dissociate the harming of animals from the flesh on the plate. Researchers say “These strategies can be direct and explicit, such as denial of animals’ pain, moral status, or intelligence, endorsement of a hierarchy in which humans are placed above non-human animals” (using religion and god to amplify the belief that animals were created solely for humans, and had no independent importance for the planet, except as food and products). The French are taught, for instance, that animals cannot think.

Added to this is the justification of meat consumption based on spurious nutritional grounds. Doctors and dieticians, who are unwitting tools of the “nutritional science” industry, put their stamp on this shameless hard sell.

The most important of all these strategies, and the one that has a profound effect on meat consumption, is the dissociation of meat from its animal origins. Important studies have been done on this (Kunst & Hohle, 2016; Rothgerber, 2013; Tian, Hilton & Becker, 2016; Foer, 2009; Joy, 2011; Singer, 1995). “At the core of the meat paradox is the experience of cognitive dissonance. Cognitive dissonance theory proposes that situations involving conflicting behaviours, beliefs or attitudes produce a state of mental discomfort (Festinger, 1957). If a person holds two conflicting, or inconsistent pieces of information, he feels uncomfortable. So, the mind strives for consistency between the two beliefs, and attempts are made to explain or rationalize them, reducing the discomfort. So, the person distorts his/her perception wilfully and changes his/her perception of the world.

The meat eater actively employs dissociation as a coping strategy to regulate his conscience, and simply stops associating meat with animals.

In earlier hunter-gatherer and agricultural societies, people killed or saw animals killed for their table. But from the mid-19th century the eater has been separated from the meat production unit. Singer (1995) says that getting meat from shops, or restaurants, is the last step of a gruesome process in which everything, but the finished product, is concealed. The process: the loading of animals into overcrowded trucks, the dragging into killing chambers, the killing, beheading, removing of skin, cleaning of blood, removal of intestines and cutting the meat into pieces, is all secret and the eater is left with neatly packed, ready-to-cook pieces with few reminders of the animal. No heads, bones, tails, feet. The industry manipulates the mind of the consumer so that he does not think of the once living and intelligent animal.

The language is changed concealing the animal. Pig becomes pork, sausage, ham, bacon, cows become beef and calves become veal, goat becomes mutton and hens become chicken and white meat. And now all of them have become protein.

Then come rituals and traditions which remove any kind of moral doubt. People often partake in rituals and traditions without reflecting on their rationale or consequences. Thanksgiving is turkey, Fridays is fish. In India all rituals were vegetarian. Now, many weddings serve meat. Animal sacrifice to the gods is part of this ritual.

Studies have found that people prefer, or actively choose, to buy and eat meat that does not remind them of the animal origins (Holm, 2018; Te Velde et al.,2002. But Evans and Miele (2012), who investigated consumers’ interactions with animal food products, show that the fast pace of food shopping, the presentation of animal foods, and the euphemisms used instead of the animal (e.g., pork, beef and mutton) reduced consumers’ ability to reflect upon the animal origins of the food they were buying. Kubberod et al. (2002) found that high school students had difficulty in connecting the animal origins of different meat products, suggesting that dissociation was deeply entrenched in their consuming habits. Simons et al. found that people differed in what they considered meat: while red meat and steak was seen as meat, more processed and white meat (like chicken nuggets e.g.) was sometimes not seen as meat at all, and was often not considered when participants in the study reported the frequency of their meat eating.

Kunst and Hohle (2016) demonstrated how the process of presenting and preparing meat, and deliberately turning it from animal to product, led to less disgust and empathy for the killed animal and higher intentions to eat meat. If the animal-meat link was made obvious – by displaying the lamb for instance, or putting the word cow instead of beef on the menu – the consumer avoided eating it and went for a vegetarian alternative. This is an important finding: by interrupting the mental dissociation, meat eating immediately went down. This explains how, during COVID, the pictures of the Chinese eating animals in Wuhan’s markets actually put off thousands of carnivores and meat sale went down. In experiments by Zickfeld et al. (2018) and Piazza et al. (2018) it was seen that showing the pictures of animals, especially young animals, reduce people’s willingness to eat meat.

Do gender differences exist when it comes to not thinking about the meat one eats?

In Kubberød and colleagues’ (2002) study on disgust and meat consumption, substantial differences emerged between females and males. Men were more aware of the origins of different types of meat, yet did not consider the origins when consuming it. Women reported that they did not want to associate the meat they ate with a living animal, and that reminders would make them uncomfortable and sometimes even unable to eat the meat. In a study by Bray et al. (2016), who investigated parents’ conversations with their children about the origins of meat, women were more likely than men to avoid these conversations with their children, as they felt more conflicted about eating meat themselves. In a study by Kupsala (2018) female consumers expressed more tension related to the thought of killing animals for food than men. The supermarket customer group preferred products that did not remind them of animal origins, and showed a strong motivation to avoid any clues that highlighted the meat-animal connection. What emerged was that the females felt that contact with, and personification of, food producing animals would sometimes make it impossible for them to eat animal products.

What are the other dissociation techniques that companies and societies use to make people eat meat. For men, the advertising is direct: Masculinity, the inevitable fate of animals, the generational traditions of their family. For women it is far more indirect: just simply hiding the source of the meat and giving the animal victim a cute name to prevent disgust and avoidance.

Kubberod et al. (2202) compared groups from rural and urban areas but found little evidence for differences between these groups. Moreover, both urban and rural consumers in the study agreed that meat packaging and presentation functioned to conceal the link between the meat and the once living animal. Both groups of respondents also stated that if pictures of tied up pigs, or pigs in stalls, would be presented on packaging of pork meat, or pictures of caged hens on egg cartons, they would not purchase the product in question.

Are people who are sensitive to disruptions of the dissociation process (or, in plain English, open to learning the truth about the lies they tell themselves) more likely to become vegetarians? Probably. Everyone has a conscience. The meat industry has tried to make you bury it. We, in the animal welfare world, should try to make it active again.

(To join the animal welfare movement contact gandhim@nic.in,www.peopleforanimalsindia.org)