Midweek Review

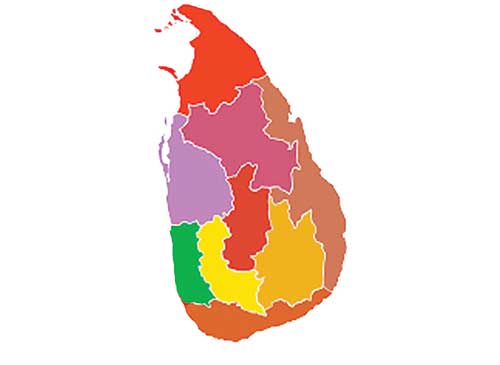

Province-based Devolution in Sri Lanka: a Critique

by G H Peiris

1. Preamble

This article is prompted by the recent announcement that the Cabinet will soon consider a proposal to conduct Provincial Council (PC) elections without delay. The article is intended to urge that the PC system should be abolished and replaced by constitutional devices to ensure: (a) genuine sharing of political power among all primordial, áscriptive and associational groups that constitute the nation of Sri Lanka; and (b) the statutory protection of Sri Lanka’s sovereignty and territorial integrity which the PC system, as long as it is permitted to last, will remain in dire peril. The article is also intended to stimulate the memory of those who appear to have forgotten the circumstances that culminated in the enactment of legislation in 1987 to establish PCs. There appears to prevail a measure of complacency among some of our present political stalwarts based on the notion that, with their two-thirds majority in Parliament, and with the 20th Amendment in place, they ought to let the status quo remain intact. This, I think, is quite silly. Apart from the fact that landslide electoral victories tend often to be brittle, those who were in the forefront of empowering the present regime are already reacting with dismay to the decision to re-establish the PCs.

2. Indo-Lanka Accord – the Indian Intervention

It is often forgotten that the government of India employed the most diabolical forms of diplomatic, military and economic coercion a powerful country could conceivably brought to bear upon a supposedly friendly nation with which it shares many cultural traits.

Omitting (for the sake of brevity) the vicissitudinous political career of Smt. Indira Gandhi during the 1970s, my elaboration of the foregoing observation begins with the commencement of her second spell of office as Prime Minister of India (January 1980 to October 1984) in the course of which she made no secret about her intense antipathy towards the JRJ-led government of Sri Lanka. This prompted certain emissaries of the ‘Tamil United Liberation Front’ (TULF) to suggest to her the desirability of launching an armed intervention in Sri Lanka of the type she had so successfully achieved at the “Liberation” of Bangladesh in 1971. That did not happen, probably because the JRJ regime had the backing of the West and the tragic end of her life in 1984. Regarding her malignant imprint on the constitutional affairs of Sri Lanka, however, it is worth citing the testimony of J. N. Dixit, Delhi’s High Commissioner in Colombo when (in his own words) he was “… involved in the most important and critical phase of Indo-Lanka relations; a period during which India’s mediatory efforts reached its peak culminating in the signing of the Indo-Lanka Agreement of 29 July 1987”. (Dixit, 1998: xvi):

“Once Mrs. Gandhi decided to be supportive of the cause of Sri Lankan Tamils on the basis of Indian interests and strategic considerations, the rest of the process which culminated in the Indo-Lanka Agreement and the induction of the IPKF was more or less inevitable”. (emphasis added)

Several reasons, partly conjectural, have been adduced for Smt. Gandhi’s hostility towards the government of Sri Lanka. For instance, She might have been resentful of Sri Lanka’s foreign policy leanings towards the ‘West’, and the reciprocal support which JRJ was attracting in abundance from some of the leading global powers for the mammoth development projects being implemented within the framework of ‘economic liberalisation’. Another explanation is that, with the worsening of relations between the Federal government and State governments of Punjab, Kashmir, Assam and West Bengal, Smt. Gandhi placed priority on consolidating her electoral support in Tamilnadu, which meant, among other things, greater concern on the demands of the Tamils in Sri Lanka. My own hunch is that it was a Shakespearian display of “Hell hath no fury as a woman scorned” towards JRJ, allegedly for an absurd insult he had hurled at her in the course of an ‘After Dinner’ speech as the Janatha government’s PM, Moraji Desai’s, guest of honour.

Be that as it may, Smt. Gandhi began to provide clandestine aid (financial, material and training in guerrilla offensives) to groups of Sri Lankan Tamil insurgents, even after it was made public knowledge through prestigious Indian journals. This is relevant background to an understanding of the disastrous anti-Tamil riot that occurred in Sri Lanka in July 1983.

The riot caused extensive damage to life and property, and a massive displacement of the Sri Lankan Tamil population in the Sinhalese-majority areas ̶ one which included a large outflow of refugees from the country. It disrupted the economy aand brought the ‘liberalisation’ boom to an abrupt end. It tarnished the image of Sri Lanka abroad, generated a global tide of sympathy towards the Tamils, and attracted international attention and concern towards Tamil grievances. It paved the way for the direct intervention of India (untrammelled by pressures from the ‘West’) in the internal affairs of Sri Lanka, culminating in the introduction in 1987 of a massive Indian Peace-Keeping Force (IPKF). It also represented a major turning point in the history of Tamil politics in Sri Lanka, with the militant groups and their strategy of armed confrontation and terrorism gaining ascendancy over the older Tamil political parties and their proclaimed commitments to peaceful agitation and protest. The militants became a power in their own right, abandoning their earlier role as the ‘boys’ of the Tamil leadership in the political mainstreams.

Indian Intervention after the Convulsions of ‘Black July’

Smt. Indira Gandhi’s offer to “mediate” in the Sri Lankan imbroglio (pre-empting other global powers from claiming that role) could not have been turned down by the beleaguered President Jayewardene.

The process of mediation commenced with the arrival of the Indian diplomat, Parthasarathi Rao. It took the form of coercing the Sri Lanka government to change its policy of decentralisation of ‘development administration’ to devolution of political power, and to change the spatial framework for such devolution from the District to the Province, along with an amalgamation of the Northern Province and the Eastern Province. His “mission” ended with the production of document referred to in subsequent negotiations as ‘Annexure C’ which he took back to Delhi. To what this document was annexed, and whether there were other “Annexures” are not known.

‘Annexure C’, and Sri Lanka government’s own proposals were presented to an ‘All Party Conference (APC) summoned by JRJ at which there was vehement opposition to certain sections of that Annexure. But the government extracted from the APC proceedings a draft Ordinance providing for (a) “a revitalised District Councils” system and (b) the establishment of a Second Chamber, and tabled the drafts for further dialogue with the TULF (the SLFP delegates having withdrawn from the APC). Up to about the end of the year, the TULF leadership maintained that the draft ordinance did form the basis of an acceptable settlement. But, thereafter, in a sudden volte-face, they rejected it outright.

Smt. Indira Gandhi was assassinated by Sikh militants on 31 October 1984. Her son, Rajiv was sworn in as PM later on the same day. Critics have maintained that this caused a change in Indo-Lanka relations in the sense that Rajiv tended to be less “imperial” than his late mother in his approach to conflict resolution both within and outside India.

Despite Rajiv’s affable demeanour, the policy transformation brought about by his succession was less tangible than what most observers would have us believe.

For instance:

(a) the Delhi government made available through the State government of Tamilnadu a grant of US$ 3.2 million to the LTTE leadership; (b) as Lalith Athulathmudali (Sri Lanka’s Minister of Security and Defence) had observed, a leaked RAW document indicated the continuing existence of training camps and bases for Sri Lankan Tamil separatist activists and; (c) despite repeated requests by JRJ, Delhi did not adopt coastal surveillance measures to curtail clandestine movement of people and commodities across Palk Strait.

Meanwhile the Tamil militants escalated their terrorist onslaught, the most horrendous event of which was the slaughter by LTTE operatives of 148 devotees (most of them elderly women) at the premises of the Sri Maha Bōdhi shrine in the sacred city of Anuradhapura, and another 16 civilians in the course of their retreat into the wilds of Wilpattu on May 14, 1985. There was media speculation that firearms used by the Tigers in this massacre were purchased by the LTTE with the aforesaid Indian grant.

Romesh Bhandari, Rajiv’s Foreign Secretary, initiated peace negotiations between the government and delegates of the secessionist groups at a forum staged in July/August 1985 in the capital of Bhutan, and thus labelled as the ‘Thimpu Talks’. It provided a forum to Tamil militants for worldwide propaganda for their ‘liberation’ demands that were set out as follows (lawyer N. Balendran acting as their spokesman):

“It is our considered view that any meaningful solution to the national question of the island must be based on the following four cardinal principles:

(1) Recognition of the Tamils of Sri Lanka as a distinct nationality,

(2) Recognition of an identified Tamil homeland and the guarantee of its territorial integrity,

(3) Based on the above, recognition of the inalienable right of self-determination of the Tamil nation,

(4) Recognition of the right to full citizenship and other fundamental democratic rights of all Tamils, who look upon the island as their home.”

The Sri Lanka delegation response, as presented by H. L. de Silva (recorded in Balendran’s monograph on the ‘Thimpu Talks’) was as follows:

“First, we observe that there is a wide range of meanings that can attach to the concepts and ideas embodied in the four principles, and our response to them would accordingly depend on the meaning and significance that is sought to be applied to them. Secondly, we must state quite emphatically that if the first three principles are to be taken at their face value and given their accepted legal meaning they are wholly unacceptable to the government. They must be rejected for the reason that they constitute a negation of the sovereignty and territorial integrity of Sri Lanka; they are detrimental to a united Sri Lanka and are inimical to the interests of the several communities, ethnic and religious in our country”.

The collapse of ‘Thimpu Talks’ prompted Bhandari, in barely concealed personal disgust at the arrogance and recalcitrance of Mr. Balendran and his entourage of secessionist militants, to summon a follow-up negotiations in Delhi at which he restricted Sri Lanka participation to delegates of the government and of the TULF. At the conclusion of that effort in August 1985 a document named the ‘Delhi Accord’, “initialled” by representatives of the two governments, was released to the media by India’s Foreign Office. It claimed that a measure of consensus was reached on ‘Province’ as the unit of devolution’ and on the powers to be devolved. The Delhi Accord was rejected by the LTTE. By the end of the year the TULF leadership had also rejected the ‘Delhi Accord’.

Thereafter there was a series of discussions between representatives of the two governments. A. P. Venkateswaran, appointed Foreign Secretary in January 1987, attempted unilaterally to make the ‘Delhi Accord’ more acceptable to the TULF by bringing the Accord offers close to a federal form of government.

Perhaps the greatest betrayal of the trust which the government of Sri Lanka had placed in the Rajiv regime was represented by Delhi’s reaction to the military campaign termed ‘Operation Liberation’ launched by the government on 26 May 1987 in the face of which the Tiger cadres, abandoned their Thalaivar’s bravado, and fled in disarray. An SOS appeal conveyed by the LTTE leadership to Tamilnadu resulted in a flotilla of fishing vessels sailing out in the guise of a “spontaneous” civilian response but, in fact, with the backing of the central and state governments. That maritime invasion was foiled by the Sri Lanka Nsavy. Thereupon, in a blatant violation of international law and Sri Lanka’s air space, a convoy of Mirage-2000 combat planes dropped 20 tons of food and medical supplies on Jaffna, ostensibly as a ‘mercy mission’, but in reality, a demonstration of what Delhi could do unless Sri Lanka obeys. At the commencement of ‘Operation Liberation’, Dixit informed Lalith Athulathmudali that India would not stand idly by if the Sri Lanka Army attempts to capture Jaffna (K. M. de Silva, 1994: 631).

The JRJ-Rajiv dialogue at the ‘SAARC Summit’ conducted at Bangalore in early 1987; discussions between Indian VIPs like Dinesh Singh and P. Chidambaran and Sri Lanka ministers like Lalith Athulathmudali, Gamini Dissanayake and A C S Hameed; and, more geerally, the enforcement of his will on senior bureaucrats in Colombo by J N Dixit (who, by this stage, had earned for himself the epithet ‘India’s Viceroy’) were among the Indo-Lanka interactions that brought about the signing of the agreement.

What I have sketched above is only the bare outline of how and why the aging President JRJ, nudging 80, succumbed to the ruthless Indian onslaught, disillusioned as he was, by the disintegration of his inner circle of loyalists, the aggressive extra-parliamentary campaign led by Sirimavo Bandaranaike, and the ethos of anarchy and violence created by the JVP whose oft repeated theme, disseminated through the calligraphically unique poster campaign, was ‘jay ăr maramu’ (‘let’s kill JR’). Soon after the signing of the Indo-Lanka Accord, the JVP almost succeeded in doing that in a grenade attack on UNP parliamentary group meeting.

Indo-Lanka Accord’: Its Political Backdrop in Sri Lanka

Politics of insurrection gathered momentum in Jaffna at least from about a decade earlier than the signing of the said ‘Accord’ when the mainstream Tamil parties began to pursue a strategy of nurturing insurgent groups, and inculcating the notion of Sinhalese oppression (rather than inequities inherent to the mismanaged economy being experienced by all ethnic groups, and the blatant Caste-based oppression endemic to the Sri Lankan Tamil social milieu) being the root cause for their deprivations. It should also be recalled that the benefits of economic buoyancy that ushered in by the policy transformation of ‘liberalization of the economy’ from the earlier pseudo-socialist shackles, initiated by the government elected to office in 1977, were scarcely felt in the predominantly Tamil areas of the north.

It was in the context of intensifying turbulence that the leaders of Ilangai Tamil Arasi Kachchi (ITAK), All-Ceylon Tamil Congress (ACTC) and Ceylon Workers Congress (CWC) formed a coalition named the Tamil United Liberation Front (TULF). At its inaugural session conducted in May 1976, the TULF adopted the so-called ‘Vaddukodai Resolution’, the opening statement of which reads as follows:

“The convention resolves that the restoration and reconstitution of the Free, Sovereign, Secular state of TAMIL EELAM based on the right of self-determination inherent to every nation has become inevitable in order to safeguard the very existence of the Tamil Nation in this Country”.

The concluding paragraphs of that ‘Resolution’ (copied below) should, in retrospect, be understood as epitomising a formal decision to launch of an ‘Eelam War’.

“This convention calls upon its ‘LIBERATION FRONT’ to formulate a plan of action and launch without undue delay the struggle for winning the sovereignty and freedom of the Tamil Nation.”, followed by more specific belligerence,

“And this Convention calls upon the Tamil Nation in general and the Tamil youth in particular to come forward to throw themselves fully in the sacred fight for freedom and to flinch not until the goal of a sovereign state of TAMIL EELAM is reached”.

The campaign rhetoric of the TULF was somewhat more vicious than its belligerence at Vaddukoddai.. At a public rally conducted shortly after the formation in 1976 of the ACTC-ITAK alliance with qualified support from Arumuga Thondaman’s ‘Ceylon Workers Congress’, the person who could have been called the ‘First Lady’ of that alliance said in the course of her speech: “I will not rest until I wear slippers turned out of Sinhalese skins”. Unbelievable? If it is, look up the ‘Report of the Commission of Inquiry’ into the communal disturbances of 1977 conducted by a former Supreme Court Judge (a person belonging to the Burgher community), published as Sessional Paper XII of 1980.

The data tabulated below show that the TULF appeal did not get the expected response even from the people living in the ‘North-East’. It is, of course, true that all contestants fielded by the TULF did win their seats in the Northern Province, securing comfortable majorities in the districts of Jaffna, Kilinochchi and Vavuniya; but elsewhere in the province, the margins of victory were wafer-thin. The polling outcome of the Eastern Province probably shocked the TULF leadership and certainly caused widespread surprise, especially since less than one-third of the voters of Batticaloa District (where Tamils accounted for 72%, and the ‘Sri Lankan Tamils 71% the district population) only 32% had endorsed the ‘Eelam’ appeal.

By the early 1980s, several groups had taken control over acts of terrorism and sabotage in Jaffna peninsula. The violence perpetrated by the insurgents and the retaliatory acts of the security forces reached fever-pitch on the eve of elections to the newly instituted District Development Councils. It resonated in other parts of the country in the form of two relatively brief waves of mob attacks on Tamil civilians, one in 1980 and the other in 1981. The victims included ‘Indian Tamils’.

The economic upsurge in the first 6 years of the JRJ-led government was short lived, and the political hopes proved to be illusory. The Jaffna peninsula turbulence was perceived by the government as a ‘law and order problem’ ̶ which a police contingent led by a Deputy Inspector General of Police Rudhra Rajasingham, a Tamil officer of impeccable repute, was ordered by the President to “eradicate within three months”. It failed in the face of massive protest campaigns, intensifying guerrilla attacks on government institutions and the security forces, and harsh retaliatory action by the security forces.

The ‘Eelam War’ for which the groundwork had been laid by the TULF was triggered off by the anti-Tamil riot of unprecedented brutality that took place in July 1983. Its damning repercussions were referred to earlier in this memorandum. JRJ reacted by proscribing several parties and incarcerating a few among his more articulate detractors, some, on the basis of barely credible evidence. Yet another blunder by him at this state was the holding of a national referendum in order to extend the life of the parliament (with the 4/5th majority under his command) by another 6 years. Apart from the rampant malpractices that features this poll, it did look like the fulfilment of his euphoric pledge in the aftermath of his victory to “roll back the electoral map”.

The youth unrest in the Northeast which was mobilised for electoral gain by the TULF began to be replicated in earnest elsewhere in the island in the form of the second wave of insurrection launched by the Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (JVP/Peoples Liberation Front). In the economic recession that prevailed, and with the incessant Television displays of unattainable luxury restricted to the life styles of a small minority, increasing numbers of youth suffering from “frustration aggression” were attracted to the JVP fold. By 1985, they engaged in raids for the collection of money and arms, crippling the economy with frequently enforced curfews, and a range of terrorist violence such as intimidation, torture and the murder of persons identified as collaborators of the government.

The Province as a Unit of Devolution

The Colebrooke-Cameron Reforms of 1833 that introduced a network of 5 Provinces was intended to consolidate British rule over the island which remained tenuous even after the suppression of the rebellion of 1818. The spatial pattern of provinces was changes from time to time until it was finalised in 1889 against the backdrop of the mid-Victorian imperial glory and the absence of any challenge to British supremacy in ‘Ceylon’. The population of the island at that time was only 3 million; and, despite the ongoing deforestation of the Central Highlands, at least about 70% of the island territory was uncharted wilderness.

To be Continued

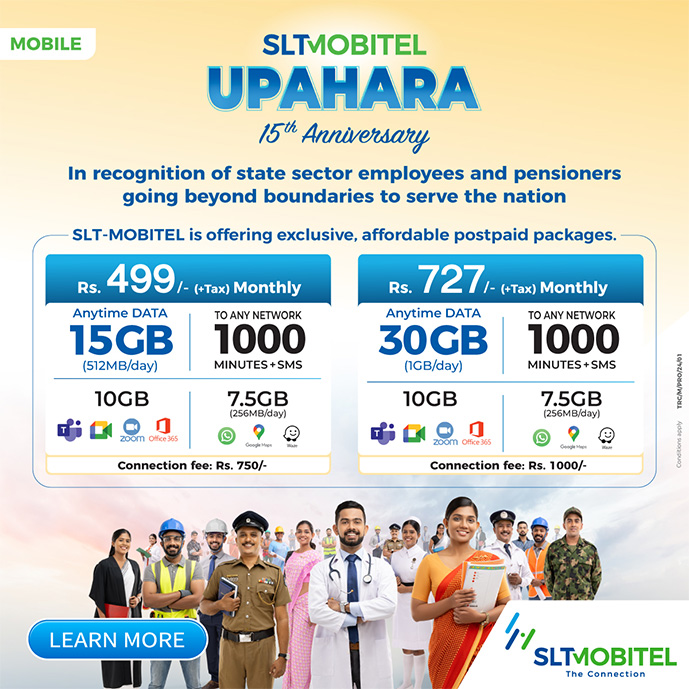

- News Advertiesment

See Kapruka’s top selling online shopping categories such as Toys, Grocery, Flowers, Birthday Cakes, Fruits, Chocolates, Clothing and Electronics. Also see Kapruka’s unique online services such as Money Remittence,News, Courier/Delivery, Food Delivery and over 700 top brands. Also get products from Amazon & Ebay via Kapruka Gloabal Shop into Sri Lanka.

Midweek Review

‘Professor of English Language Teaching’

It is a pleasure to be here today, when the University resumes postgraduate work in English and Education which we first embarked on over 20 years ago. The presence of a Professor on English Language Teaching from Kelaniya makes clear that the concept has now been mainstreamed, which is a cause for great satisfaction.

Twenty years ago, this was not the case. Our initiative was looked at askance, as indeed was the initiative which Prof. Arjuna Aluwihare engaged in as UGC Chairman to make degrees in English more widely available. Those were the days in which the three established Departments of English in the University system, at Peradeniya and Kelaniya and Colombo, were unbelievably conservative. Their contempt for his efforts made him turn to Sri Jayewardenepura, which did not even have a Department of English then and only offered it as one amongst three subjects for a General Degree.

Twenty years ago, this was not the case. Our initiative was looked at askance, as indeed was the initiative which Prof. Arjuna Aluwihare engaged in as UGC Chairman to make degrees in English more widely available. Those were the days in which the three established Departments of English in the University system, at Peradeniya and Kelaniya and Colombo, were unbelievably conservative. Their contempt for his efforts made him turn to Sri Jayewardenepura, which did not even have a Department of English then and only offered it as one amongst three subjects for a General Degree.

Ironically, the most dogmatic defence of this exclusivity came from Colombo, where the pioneer in English teaching had been Prof. Chitra Wickramasuriya, whose expertise was, in fact, in English teaching. But her successor, when I tried to suggest reforms, told me proudly that their graduates could go on to do postgraduate degrees at Cambridge. I suppose that, for generations brought up on idolization of E. F. C. Ludowyke, that was the acme of intellectual achievement.

I should note that the sort of idealization of Ludowyke, the then academic establishment engaged in was unfair to a very broadminded man. It was the Kelaniya establishment that claimed that he ‘maintained high standards, but was rarefied and Eurocentric and had an inhibiting effect on creative writing’. This was quite preposterous coming from someone who removed all Sri Lankan and other post-colonial writing from an Advanced Level English syllabus. That syllabus, I should mention, began with Jacobean poetry about the cherry-cheeked charms of Englishwomen. And such a characterization of Ludowyke totally ignored his roots in Sri Lanka, his work in drama which helped Sarachchandra so much, and his writing including ‘Those Long Afternoons’, which I am delighted that a former Sabaragamuwa student, C K Jayanetti, hopes to resurrect.

I have gone at some length into the situation in the nineties because I notice that your syllabus includes in the very first semester study of ‘Paradigms in Sri Lankan English Education’. This is an excellent idea, something which we did not have in our long-ago syllabus. But that was perhaps understandable since there was little to study then except a history of increasing exclusivity, and a betrayal of the excuse for getting the additional funding those English Departments received. They claimed to be developing teachers of English for the nation; complete nonsense, since those who were knowledgeable about cherries ripening in a face were not likely to move to rural areas in Sri Lanka to teach English. It was left to the products of Aluwihare’s initiative to undertake that task.

Another absurdity of that period, which seems so far away now, was resistance to training for teaching within the university system. When I restarted English medium education in the state system in Sri Lanka, in 2001, and realized what an uphill struggle it was to find competent teachers, I wrote to all the universities asking that they introduce modules in teacher training. I met condign refusal from all except, I should note with continuing gratitude, from the University of Sri Jayewardenepura, where Paru Nagasunderam introduced it for the external degree. When I started that degree, I had taken a leaf out of Kelaniya’s book and, in addition to English Literature and English Language, taught as two separate subjects given the language development needs of students, made the third subject Classics. But in time I realized that was not at all useful. Thankfully, that left a hole which ELT filled admirably at the turn of the century.

The title of your keynote speaker today, Professor of English Language Teaching, is clear evidence of how far we have come from those distant days, and how thankful we should be that a new generation of practical academics such as her and Dinali Fernando at Kelaniya, Chitra Jayatilleke and Madhubhashini Ratnayake at USJP and the lively lot at the Postgraduate Institute of English at the Open University are now making the running. I hope Sabaragamuwa under its current team will once again take its former place at the forefront of innovation.

To get back to your curriculum, I have been asked to teach for the paper on Advanced Reading and Writing in English. I worried about this at first since it is a very long time since I have taught, and I feel the old energy and enthusiasm are rapidly fading. But having seen the care with which the syllabus has been designed, I thought I should try to revive my flagging capabilities.

However, I have suggested that the university prescribe a textbook for this course since I think it is essential, if the rounded reading prescribed is to be done, that students should have ready access to a range of material. One of the reasons I began while at the British Council an intensive programme of publications was that students did not read round their texts. If a novel was prescribed, they read that novel and nothing more. If particular poems were prescribed, they read those poems and nothing more. This was especially damaging in the latter case since the more one read of any poet the more one understood what he was expressing.

Though given the short notice I could not prepare anything, I remembered a series of school textbooks I had been asked to prepare about 15 years ago by International Book House for what were termed international schools offering the local syllabus in the English medium. Obviously, the appalling textbooks produced by the Ministry of Education in those days for the rather primitive English syllabus were unsuitable for students with more advanced English. So, I put together more sophisticated readers which proved popular. I was heartened too by a very positive review of these by Dinali Fernando, now at Kelaniya, whose approach to students has always been both sympathetic and practical.

I hope then that, in addition to the texts from the book that I will discuss, students will read other texts in the book. In addition to poetry and fiction the book has texts on politics and history and law and international relations, about which one would hope postgraduate students would want some basic understanding.

Similarly, I do hope whoever teaches about Paradigms in English Education will prescribe a textbook so that students will understand more about what has been going on. Unfortunately, there has been little published about this but at least some students will I think benefit from my book on English and Education: In Search of Equity and Excellence? which Godage & Bros brought out in 2016. And then there was Lakmahal Justified: Taking English to the People, which came out in 2018, though that covers other topics too and only particular chapters will be relevant.

The former book is bulky but I believe it is entertaining as well. So, to conclude I will quote from it, to show what should not be done in Education and English. For instance, it is heartening that you are concerned with ‘social integration, co-existence and intercultural harmony’ and that you want to encourage ‘sensitivity towards different cultural and linguistic identities’. But for heaven’s sake do not do it as the NIE did several years ago in exaggerating differences. In those dark days, they produced textbooks which declared that ‘Muslims are better known as heavy eaters and have introduced many tasty dishes to the country. Watalappam and Buriani are some of these dishes. A distinguished feature of the Muslims is that they sit on the floor and eat food from a single plate to show their brotherhood. They eat string hoppers and hoppers for breakfast. They have rice and curry for lunch and dinner.’ The Sinhalese have ‘three hearty meals a day’ and ‘The ladies wear the saree with a difference and it is called the Kandyan saree’. Conversely, the Tamils ‘who live mainly in the northern and eastern provinces … speak the Tamil language with a heavy accent’ and ‘are a close-knit group with a heavy cultural background’’.

And for heaven’s sake do not train teachers by telling them that ‘Still the traditional ‘Transmission’ and the ‘Transaction’ roles are prevalent in the classroom. Due to the adverse standard of the school leavers, it has become necessary to develop the learning-teaching process. In the ‘Transmission’ role, the student is considered as someone who does not know anything and the teacher transmits knowledge to him or her. This inhibits the development of the student.

In the ‘Transaction’ role, the dialogue that the teacher starts with the students is the initial stage of this (whatever this might be). Thereafter, from the teacher to the class and from the class to the teacher, ideas flow and interaction between student-student too starts afterwards and turns into a dialogue. From known to unknown, simple to complex are initiated and for this to happen, the teacher starts questioning.’

And while avoiding such tedious jargon, please make sure their command of the language is better than to produce sentences such as these, or what was seen in an English text, again thankfully several years ago:

Read the story …

Hello! We are going to the zoo. “Do you like to join us” asked Sylvia. “Sorry, I can’t I’m going to the library now. Anyway, have a nice time” bye.

So Syliva went to the zoo with her parents. At the entrance her father bought tickets. First, they went to see the monkeys

She looked at a monkey. It made a funny face and started swinging Sylvia shouted: “He is swinging look now it is hanging from its tail its marvellous”

“Monkey usually do that’

I do hope your students will not hang from their tails as these monkeys do.

Midweek Review

Little known composers of classical super-hits

By Satyajith Andradi

Quite understandably, the world of classical music is dominated by the brand images of great composers. It is their compositions that we very often hear. Further, it is their life histories that we get to know. In fact, loads of information associated with great names starting with Beethoven, Bach and Mozart has become second nature to classical music aficionados. The classical music industry, comprising impresarios, music publishers, record companies, broadcasters, critics, and scholars, not to mention composers and performers, is largely responsible for this. However, it so happens that classical music lovers are from time to time pleasantly struck by the irresistible charm and beauty of classical pieces, the origins of which are little known, if not through and through obscure. Intriguingly, most of these musical gems happen to be classical super – hits. This article attempts to present some of these famous pieces and their little-known composers.

Pachelbel’s Canon in D

The highly popular piece known as Pachelbel’s Canon in D constitutes the first part of Johann Pachelbel’s ‘Canon and Gigue in D major for three violins and basso continuo’. The second part of the work, namely the gigue, is rarely performed. Pachelbel was a German organist and composer. He was born in Nuremburg in 1653, and was held in high esteem during his life time. He held many important musical posts including that of organist of the famed St Stephen’s Cathedral in Vienna. He was the teacher of Bach’s elder brother Johann Christoph. Bach held Pachelbel in high regard, and used his compositions as models during his formative years as a composer. Pachelbel died in Nuremburg in 1706.

Pachelbel’s Canon in D is an intricate piece of contrapuntal music. The melodic phrases played by one voice are strictly imitated by the other voices. Whilst the basso continuo constitutes a basso ostinato, the other three voices subject the original tune to tasteful variation. Although the canon was written for three violins and continuo, its immense popularity has resulted in the adoption of the piece to numerous other combinations of instruments. The music is intensely soothing and uplifting. Understandingly, it is widely played at joyous functions such as weddings.

Jeremiah Clarke’s Trumpet Voluntary

The hugely popular piece known as ‘Jeremiah Clarke’s Trumpet Voluntary’ appeared originally as ‘ The Prince of Denmark’s March’ in Jeremiah Clarke’s book ‘ Choice lessons for the Harpsichord and Spinet’, which was published in 1700 ( Michael Kennedy; Oxford Dictionary of Music ). Sometimes, it has also been erroneously attributed to England’s greatest composer Henry Purcell (1659 – 1695 ) and called ‘Purcell’s Trumpet Voluntary (Percy A. Scholes ; Oxford Companion to Music). This brilliant composition is often played at joyous occasions such as weddings and graduation ceremonies. Needless to say, it is a piece of processional music, par excellence. As its name suggests, it is probably best suited for solo trumpet and organ. However, it is often played for different combinations of instruments, with or without solo trumpet. It was composed by the English composer and organist Jeremiah Clarke.

Jeremiah Clarke was born in London in 1670. He was, like his elder contemporary Pachelbel, a musician of great repute during his time, and held important musical posts. He was the organist of London’s St. Paul’s Cathedral and the composer of the Theatre Royal. He died in London in 1707 due to self – inflicted gun – shot injuries, supposedly resulting from a failed love affair.

Albinoni’s Adagio

The full title of the hugely famous piece known as ‘Albinoni’s Adagio’ is ‘Adagio for organ and strings in G minor’. However, due to its enormous popularity, the piece has been arranged for numerous combinations of instruments. It is also rendered as an organ solo. The composition, which epitomizes pathos, is structured as a chaconne with a brooding bass, which reminds of the inevitability and ever presence of death. Nonetheless, there is no trace of despondency in this ethereal music. On the contrary, its intense euphony transcends the feeling of death and calms the soul. The composition has been attributed to the Italian composer Tomaso Albinoni (1671 – 1750), who was a contemporary of Bach and Handel. However, the authorship of the work is shrouded in mystery. Michael Kennedy notes: “The popular Adagio for organ and strings in G minor owes very little to Albinoni, having been constructed from a MS fragment by the twentieth century Italian musicologist Remo Giazotto, whose copyright it is” (Michael Kennedy; Oxford Dictionary of Music).

Boccherini’s Minuet

The classical super-hit known as ‘Boccherini’s Minuet’ is quite different from ‘Albinoni’s Adagio’. It is a short piece of absolutely delightful music. It was composed by the Italian cellist and composer Luigi Boccherini. It belongs to his string quintet in E major, Op. 13, No. 5. However, due to its immense popularity, the minuet is performed on different combinations of instruments.

Boccherini was born in Lucca in 1743. He was a contemporary of Haydn and Mozart, and an elder contemporary of Beethoven. He was a prolific composer. His music shows considerable affinity to that of Haydn. He lived in Madrid for a considerable part of his life, and was attached to the royal court of Spain as a chamber composer. Boccherini died in poverty in Madrid in 1805.

Like numerous other souls, I have found immense joy by listening to popular classical pieces like Pachelbel’s Canon in D, Jeremiah Clarke’s Trumpet Voluntary, Albinoni’s Adagio and Boccherini’s Minuet. They have often helped me to unwind and get over the stresses of daily life. Intriguingly, such music has also made me wonder how our world would have been if the likes of Bach, Handel, Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, and Schubert had never lived. Surely, the world would have been immeasurably poorer without them. However, in all probability, we would have still had Pachelbel’s Canon in D, Jeremiah Clarke’s Trumpet Voluntary, Albinoni’s Adagio, and Boccherini’s Minuet, to cheer us up and uplift our spirits.

Midweek Review

The Tax Payer and the Tough

By Lynn Ockersz

The tax owed by him to Caesar,

Leaves our retiree aghast…

How is he to foot this bill,

With the few rupees,

He has scraped together over the months,

In a shrinking savings account,

While the fires in his crumbling hearth,

Come to a sputtering halt?

But in the suave villa next door,

Stands a hulk in shiny black and white,

Over a Member of the August House,

Keeping an eagle eye,

Lest the Rep of great renown,

Be besieged by petitioners,

Crying out for respite,

From worries in a hand-to-mouth life,

But this thought our retiree horrifies:

Aren’t his hard-earned rupees,

Merely fattening Caesar and his cohorts?